Creative Resistance as a Performance Tool

Table of contents

DOI: 10.32063/0203

Sarah Callis

Sarah Callis is Senior Postgraduate Tutor at the Royal Academy of Music, where she focuses on practice-led research projects with masters and doctoral students. Her research involves working collaboratively with performers on the aesthetic and analytical questions that emerge from programming, rehearsal and performance, with a particular interest in the music of Brahms.

Neil Heyde

by Sarah Callis, Neil Heyde, Zubin Kanga, Olivia Sham

Music + Practice, Volume 2

Explorative

Introduction

For many classical musicians, resistance is something to be avoided. Whether in the physical act of playing, the choice of notation or the approach to interpretation, the term has negative connotations: inefficiency, ineffectiveness and even the risk of injury. Yet resistance can also be a creative catalyst. This article explores the idea of resistance as a tool in the performance of Western art music. The resistance we are discussing is not the sort that only obstructs performance; rather, creative resistance takes hold of a potential obstruction and puts it to use.

The idea that obstruction might provide a catalyst for the artistic process is perhaps more tangible in the plastic arts, and was raised in a radio interview with the sculptor Richard Deacon just before the opening of his 2014 Tate Britain retrospective Exhibition.1)Tate Britain, Richard Deacon (London, 5 February – 27 April 2014). Richard Deacon (b. 1949) is a leading British artist, best known for his abstract sculptures drawn from extensive exploration and manipulation of a wide range of different materials. Deacon was asked what would be the properties of his ideal working material, were he to invent it.

The ideal material would have flexibility and ability to change shape and then to stay, but to be able to be reconsidered … it would be translucent rather than opaque. I thought polycarbonate was quite close at one time, although I’ve stopped working with polycarbonate; wood is interesting but obviously it’s not transparent; steel is interesting because of its reflectivity; clay is interesting because of its malleability; cloth remains interesting because of what you have to do to it to put structure into it; so – umm – it might even be disappointing if you ever found the ideal material.2)Richard Deacon, ‘Interview with Mark Lawson’, Front Row 3 February, BBC Radio 4 http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01rp2v5, at 24:43. Accessed 15 July 2014.

Significant for our understanding of resistance is Deacon’s conclusion that the materials he chooses might, without their inherent challenges, become creatively ‘disappointing’. A material that is too compliant – that lacks idiosyncrasies and does not obstruct his practical encounter with it in any way – may also fail to activate his imagination. Indeed, Deacon prefers to describe himself as a ‘fabricator’ rather than a sculptor, noting that ‘when you fabricate something it has a straightforward sense of making, but it also has a sense of invention or make-believe. I always like that dual play’.3)Susan Holtham, ‘Work of the week: After by Richard Deacon’, Tate Blogs, 5 February 2014 http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/blogs/work-week-after-richard-deacon. Accessed 15 July 2014. Perhaps what Deacon has realized then is that one of the most important triggers for invention in a material might be its potential resistance.

Deacon’s experience can be compared with sociologist Richard Sennett’s discussion of the inventive possibilities of resistance in his book, The Craftsman. In the following passage, Sennett observes the potential of generated resistance, here in the field of architecture:

The designer-planner seeking to bring these dead public spaces to life can succeed by introducing what may seem unnecessary elements, such as indirect approaches to front entrances or bollards arbitrarily to mark out territory, or, as Mies van der Rohe did with the Seagram Building in New York, by contriving complicated side entrances to his elegantly simple tower. Complexity can serve as a design tool to counter neutrality. Additions of complexity can prompt people to engage more with their surroundings.4)Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), p. 225.

Mies’s ‘obstructions’ are intentional – a specific tool employed by the architect both to animate his own relationship with the building’s design, and to ensure that users retain the same active engagement with the finished structure. Where Deacon recognizes that the ‘flaws’ of his materials are in fact something he exploits, they are for Mies, a deliberate act of design. Sennett acknowledges this dual quality by observing that ‘resistances, then, can be either found or made. Both cases require toleration of frustration, and both require imagination’.5)Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 226. Sennett also makes clear that ‘making things complex’ is a feature of process rather than product, observing that:

simplicity represents a goal in craftwork – it’s a measure of what David Pye calls “soundness” in practice. But to make difficulties where none need be is a way to think about the nature of soundness.6)Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 225.

This article explores the idea that both found and made resistances can be seen as relevant to the musical performance process, although the two – as an inevitable result of the nature of performance – are often deeply intertwined. ‘Found resistance’ implies, for the performer, that resistance is already present – for example, embedded in an unusual notation or in a physical conflict with their instrument – and provokes a response; this is usually filtered through the declared or assumed strategy of composers, who may explicitly signal resistance in their notation. ‘Made resistance’, on the other hand, might suggest choosing a challenging or obscure fingering or bowing in the face of ‘straightforward’ materials, or indeed, making inroads into a complex notation by making it more complex still. In exploring such examples, we aim to demonstrate how working with resistances, both found and made, requires the adoption of a certain kind of attitude (‘a suspicion that things are not what they seem’ as Sennett puts it), one in which the performer distrusts the self-evident – or perhaps ‘archetypally musical’ – response by avoiding the most readily available tools in the box; in this sense a ‘resistant attitude’ echoes Sennett’s assertion that resistance is a ‘technique of investigation’.7)Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 225

Our discussion does not seek (or offer) a unitary or hierarchical understanding of resistance, but rather an exploration of its multiple possibilities based on a range of practical evidence. The case study material that will be explored was developed both individually and collectively within the Royal Academy of Music’s practical research environment, an environment in which musicians observe multiple (and competing) musical traditions and attitudes alongside their own practice. The term ‘resistance’ therefore gradually emerged as a label to capture certain types of creative strategy that performers shared across diverse contexts, rather than providing a starting point for enquiry. Our discussion is driven by practice rather than theory.

We are not the first to identify resistance as a productive tool for musicians. Indeed, the following discussion between György Kurtág and his wife Marta points to such a strategy:

MK: One of your principal discoveries was that in instrumental performance, a resistance has to be fitted in, the easy solution is not the right one.

GYK: Yes, but I put the resistance into works differently for different performers. My goal is exactly as Marta says but for each person, the threshold is in a different place.8)György Kurtág, Three Interviews and Ligeti Homages, compiled and ed. by Bálint András Varga (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2009), p. 30.

Kurtág here recognizes the expressive potential of generating material that obstructs the performer – he later describes it as a means to ‘make them get into the heart of the piece’.9)Kurtág, Three Interviews, p. 31. What is notable, however, is his strategy of individually targeting resistance, embedding into his notation a specific site of response. Kurtág is charging his chosen performer with recognizing these resistances and responding rigorously through their own technique, instrument and personality.10)Rachel Beckles Willson describes a particularly acute example of Kurtág’s individualized use of resistance in relation to a performance of Samuel Beckett: What is the Word performed by the singer Ildikó Monyók at the Royal Academy of Music in 2002. Kurtág’s demanding approach to his performers is legendary. Rachel Beckles Willson, ‘A study in geography, “tradition”, and identity in concert practice’, Music and Letters 85/4 (2004), pp. 602–13, here 608–9. As such Kurtág’s approach points toward the potential of found resistance for performers, highlighting that however the resistance might be embedded, their response – itself an act of resistance – must be deliberate in its action, and critical in its expressive effect.

Like Mies, performers might also design a resistance into the performance process where it does not seem inherent in the material. In his book Music and the Line of Most Resistance, Artur Schnabel famously advocated a performing life dedicated to such an approach.11)Artur Schnabel, Music and the Line of Most Resistance (New York: Da Capo, 1969 [originally published 1942]), p. 62. Schnabel’s recommendation, as described in the book, is more philosophy than method,12)Leon Botstein argues persuasively that Schnabel’s rhetoric was constructed in response to the excesses of Romantic virtuosity (p. 588) and that his uncompromising philosophy of creative struggle, when separated from the man himself, had a ‘paralyzing’ effect on the next generation (p. 593). See Leon Botstein, ‘Artur Schnabel and the Ideology of Interpretation’, Musical Quarterly, 85/4 (2001), pp. 587–94. but the opening statement of his edition of the Beethoven Sonatas is suggestive of the practical tools he employed:

Some fingerings in this edition may appear somewhat strange. In explanation of the more unusual ones let it be said that the selection was not made exclusively with a view towards technical facility, but that rather often it originated from the desire to secure – or at least encourage – the musical expression of the passages in question.13)Artur Schnabel, ed., 32 Sonatas for the Pianoforte: Ludwig van Beethoven (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1935), Editor’s Preface.

Schnabel’s often awkward fingerings offer an insight into his particular approach to the works, revealing how he chose to revisit his physical relationship with music that has a long and ingrained performing history.14)For example, in Beethoven’s op. 10 no. 3, 2nd movement, bar 43, Schnabel opts to play the sf B flat with a thumb, which seems an awkward choice considering the position of the note at the top of the phrase. However, the time taken to reach the note with the thumb is clearly designed to have a significant expressive effect, and it also enriches timbre and volume. Schnabel reinforces his idea by adding a rubato. As Sennett puts it, ‘additions of complexity can prompt people to engage more with their surroundings’.15)Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 225. Aden Evens’s discussion of a performer’s relationship with their instrument, also points to the importance of such an approach:

At some point in a musician’s training, the instrument ceases to offer adequate resistance. The interface between player and instrument becomes too smooth, and familiar patterns are so comfortable as to discourage the invention or investigation of other possibilities.16)Aden Evens, Sound Ideas: Music, Machines and Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), p. 153. Evens is discussing the work of improvisers, in particular John Corbett, but this quote is equally relevant to the performance of notated music.

He observes that performers, once expert, must reinvent the relationship they have with their instrument in an ongoing process; all instruments offer their performers a set of found resistances, but the player must also ‘re-make’ these to avoid their performances slipping into the routine and bland.17)See Liza Lim, ‘A mycelial model for understanding distributed creativity: collaborative partnership in the making of ‘Axis Mundi’ (2013) for solo bassoon’, University of Huddersfield Repository, http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ (Lim, 2013) for an exploration of the creative de-stabilization of the interface between players and the sound they produce. Evens’s use of the term ‘interface’ also points here to a typical site of resistance – like friction, it often emerges at intersections, typically between a player and their materials and collaborators. Sennett’s term for this optimum site is a ‘border’, a ‘site of exchange as well as separation’.18)Sennett, The Craftsman, pp. 227 and 231.

One way to capture our idea of resistance is to explore a living collaboration, where found and made resistances can be identified and analysed with a degree of immediacy, and where interfaces are particularly visible. In the following discussion, pianist Zubin Kanga describes a particularly relevant example that emerged from his doctoral work at the Royal Academy of Music, a larger project in which Kanga’s intensive exploration of the collaborative process helped – notably in its resonance with non-living collaborations – to clarify our understanding of resistance.19)The effects of resistance, as well as other catalysts and pressures, on composer–performer collaborations are explored in detail in Zubin Kanga, Inside the Collaborative Process: Realising New Works for Solo Piano (PhD, Royal Academy of Music, 2014); see Chapter 5 for a detailed examination of David Young’s Not Music Yet.

Zubin Kanga: Case Study 1

Modelling resistance in a living collaboration

20)Zubin Kanga’s post-doctoral position in the CTEL research centre at the University of Nice-Sophia Antipolis is part of the GEMME project on Music and Gesture, supported by funds granted by the ANR (National Agency for Research, France).

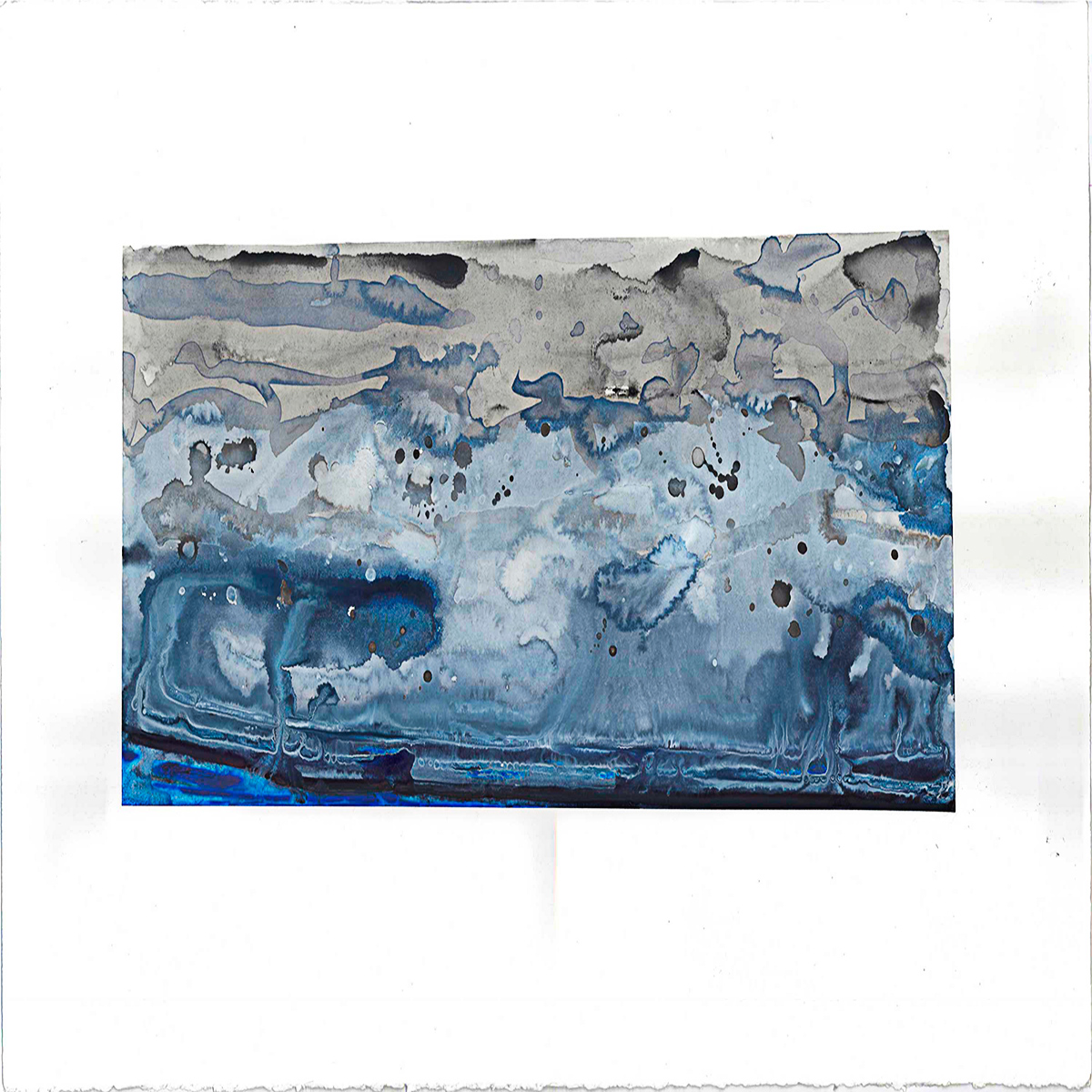

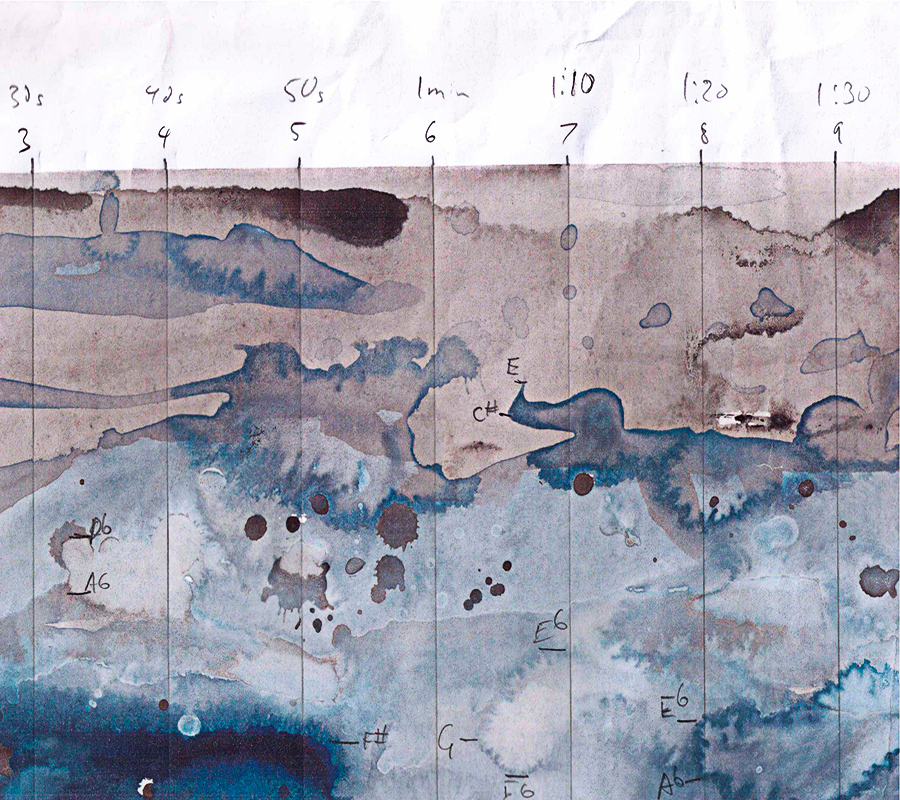

The case study involves the collaborative creation of Not Music Yet for solo piano (Sydney: Australian Music Centre, 2012), written for me by Australian composer David Young. Significantly it is notated as a painting, a format that immediately demanded that the ‘borders’ between the performer, composer, notation and instrument be negotiated in explicit terms.21)Young’s approach to collaborating around graphic notation has developed over many years of collaborations with solo performers such as pianists Mark Knoop and Michael Kieran Harvey; percussionist Eugene Ughetti; clarinettists Carl Rosman and Richard Haynes; and ensembles including Elision (Australia/UK), Ensemble Offspring (Australia), Ives Ensemble (Netherlands), Champ d’Action (Belgium), Ensemble 2000 (Denmark), Manufacture Ensemble (Japan) and Æquator (Switzerland). His largest scale work using graphic notation is his opera cycle, The Minotaur Trilogy (composed with Margaret Cameron), performed by Chamber Made Opera (Australia) in 2012. In documenting this collaboration, I was able to observe how these borders were navigated through the generation and repeated negotiation of resistance, a process that extended from commission to first performance and beyond.

The score of Not Music Yet is a large watercolour painting measuring 68 cm x 102 cm. A scan of the score is shown in Figure 1, although this does not fully capture the detail of the painting and the variety of painted textures visible in the original.

On handing it over, Young also provided an accompanying preface with detailed instructions for the interpretation of the score: the performer is to consider it a time-space score (with pitch read on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis). They should make three equal passes, reading from left to right, playing only the black parts of the painting in the first pass, followed by white and then blue. The work can be performed in either 7- or 42-minute versions, and Young recommended the use of a stopwatch to aid the exact timing of all sections and internal events. He further stated in his instructions that ‘every attempt should be made to realize the graphics’ contours and shapes as carefully and precisely as possible’.22)Young: Not Music Yet (2012). Preface.

Young’s specific instructions, and his discussions with me prior to handing over the score, made it clear that his compositional process involved activating a resistance between pianist and painting in order to trigger a very particular expressive response. The instructions seemed designed to obstruct the wide range of interpretative freedoms I might have when realizing an abstract graphic score (such as those by Earle Brown or John Cage).23)Earle Brown’s December 1952 is a classic example of an abstract graphic score intended as a focus for the performer’s imagination rather than a schematic. Cage’s graphic scores include his Concert for Piano and Orchestra (1958), which plays with different types and degrees of abstraction on each page. In both cases, the specific approach to interpreting the notation is not specified, in contrast with Young’s approach. Equally, the blurring of colours, ambiguity of shapes and detailed complexity of the painting impeded any attempt at an exact mapping of visual events into sound, as the instructions demanded. In our discussions prior to the delivery of the score, he had outlined, amongst other issues, the important influence on his work of choreographer Deborah Hay.24)Deborah Hay was born in Brooklyn. After training and working with Merce Cunningham in the 1960s, she moved to Austin, Texas, where she developed her own unique approach to choreography. In the last 20 years, her work has received numerous international prizes and has been performed across the US, Europe and Australia. According to Young, Hay’s use of Zen riddles and contradictory instructions result in her dancers having ‘no time to start inventing or interpreting or elaborating or even performing’, forcing them to ‘distrust’ their training and choreographic vocabulary in order to find new modes of expression.25)Kanga, Inside the Collaborative Process, p. 393, This mirrored the resistance Young had built into his score, where, alongside the considerable demands of interpreting the notation, I would also need to distrust my own trained impulse to ‘perform’. Like Deacon, however, these found resistances offered a stimulus for action, allowing me an entry point into the process of generating a realisation.

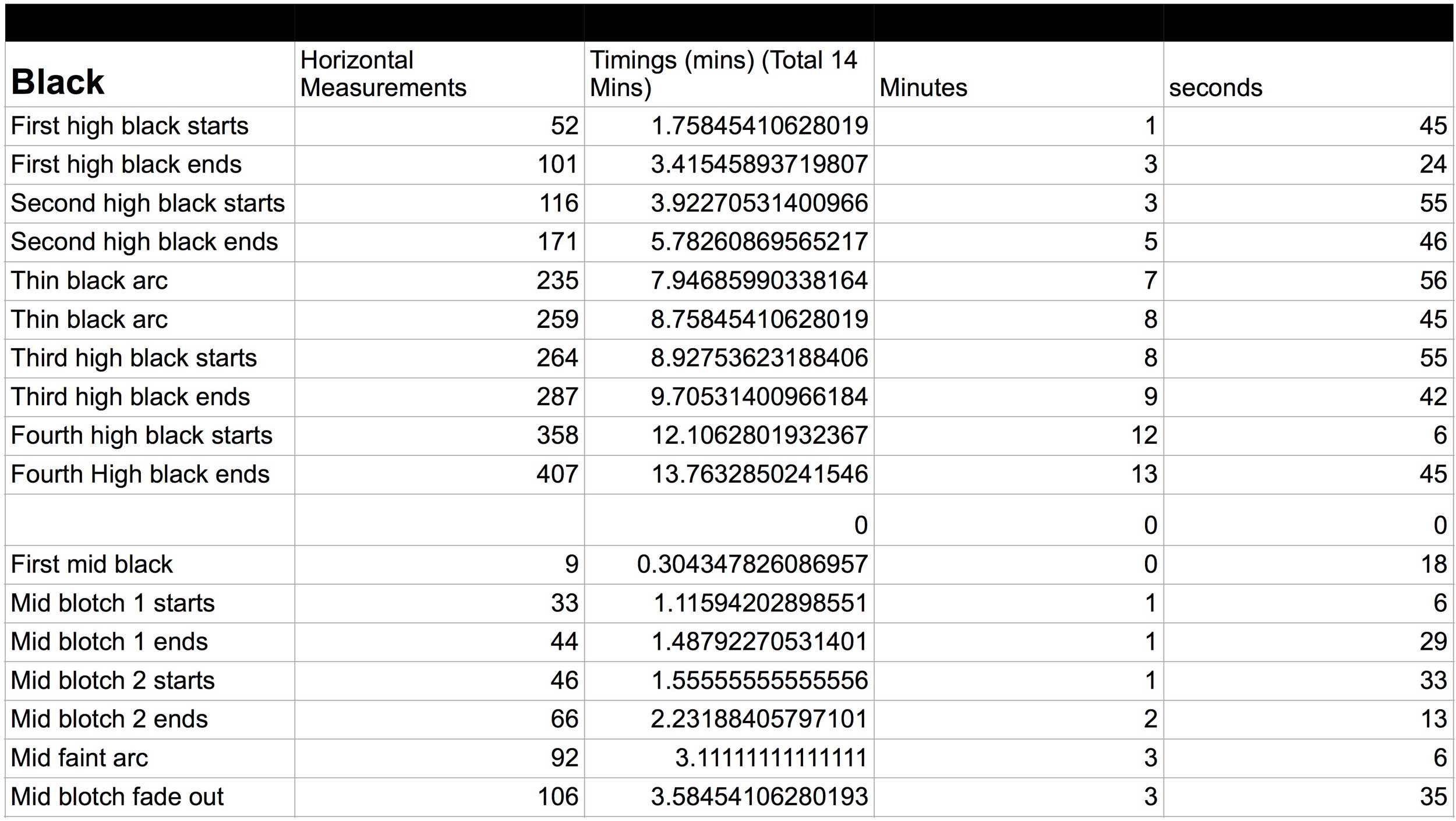

In response to these contradictory demands, I decided to adopt a strategy of ‘making things complex’ (as Sennett would describe it). I began by undertaking a detailed mapping process quantifying with great precision aspects of timing, register, colour and gesture (see Figure 2). Using this spreadsheet of measurements, I created several annotated copies of the score, with timings and divisions at the top, and pitches over the painting itself; one of the final versions is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 David Young: Not Music Yet, marked up for later performances and recording.[/caption]

Figure 3 David Young: Not Music Yet, marked up for later performances and recording.[/caption]

By creating this map, I was filling the (found) gap between painting and instructions with a highly detailed (made) plan-of-action, which offered a framework for practising, and provided me with a formal scaffolding within which I could draw on all my pianistic resources to generate a musical language that still adhered closely to the score. Furthermore, I avoided the kind of ‘too smooth’ interface with the piano that Evens describes by using contrasting sets of pianistic techniques for each ‘pass’ of the painting (percussive sounds; on the keys; and playing directly onto the strings) to create three contrasting tableaux. At different points in the process, both David and I considered conventionally notated versions of the score, his as a complement to the painting, and mine as means to performance. In both cases, we rejected this option as one that undermined the notational efficiency of the painting itself; without the resistance generated when working directly with the watercolour notation, the negotiation of roles that was core to the expressive idea of the piece could not progress.26)To some extent, we were confirming Ferneyhough’s assertion that notation expresses ‘an implied ideology of its own process of creation’. See Brian Ferneyhough, ‘Aspects of Notational and Compositional Practice’, in James Boros and Richard Toop, eds., Collected Writings (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic), pp. 2–13, here 4.

Once the workshops began, Young continued to refine his vision of the piece, requesting that I modify my initial demonstrative and extrovert approach so as to achieve something that ‘still has the same intensity, but is not as dramatic … making it a little bit more mechanical and also a tiny bit more subdued. It’s a watercolour, it’s not an acrylic’. At this point, active resistance remained between the overt virtuosity of my interpretation – utilizing my wide-ranging pianistic toolbox – and Young’s aesthetic concept of ‘non-performance’, similar to that advocated by Deborah Hay. However, as negotiations progressed, there emerged a sense of convergence toward a mutual interpretation: I continued to refine my physical relationship with the score, explaining to Young that ‘there’s some element of improvisation, but it’s [about] getting it as close to what’s there on the page’, whilst Young was focussed on activating his notational strategy, observing that ‘I think the more you are convinced that what you’re doing relates to the painting … the better it will work’. By working in tension with score and instrument, I was able to redefine my creative role as the performer of the work, and the composer was able to arrive at a point where he could declare: ‘yeah, that’s a David Young piece’.27)The quotes in this paragraph are from Kanga, Inside the Collaborative Process, pp. 416–422. The cycle of finding and making resistance generated by the competing priorities within our collaboration – notational, instrumental, aesthetic – allowed the creative territory of the piece to be gradually mapped out and validated, yet never completely resolved, a constantly regenerative process that allows the score to retain its creative potency with subsequent performances.28)For further discussion of the collaborative creation of Not Music Yet, see Zubin Kanga, ‘“Not Music Yet”: Graphic Notation as a Catalyst for Collaborative Metamorphosis’, Eras Journal, Edition 16, 2014. A live concert recording of Not Music Yet can be heard here:

Resistance in performing music from the past

The three case studies that follow explore the performance of works that originated in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and aim to show that the activation of resistance that is so visible in the Kanga/Young case study can be equally relevant in the performance of music from the past. In these case studies the composers are now absent, of course, and the nature of the creative process must be re-imagined through engagement with the materials they have left behind. It is the composer’s inability to ‘speak’ in response to the performer, however, that generates an interface between performer and composer that offers ground that is equally fertile for both found and made resistance. In interacting with Beethoven’s notation in his piano sonatas, Schnabel found the use of ‘somewhat strange’ fingerings a way to trigger his creatively unique response, and it is with a similar attitude that we look at materials as providing a tool through which established repertoire can be newly-imagined. It is also worth acknowledging that what follows will involve grappling with the minutiae of performance, what the influential Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti worried the readers of his book On the Violin would consider ‘minor points, in fact, trivia’.29)Joseph Szigeti, Szigeti on the violin (New York: Dover, 1979), xxi–xxii. Such details are vital, however, for establishing how performers gain a grip on their materials, and indeed they are a necessary means for generating resistance; as Sennett puts it: ‘it is an error… to deal first with the big difficulties and then clean up the details; good work often proceeds in just the opposite direction’.30)Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 221. The practical evidence presented in these case studies is drawn from performances, rehearsals and workshops, although each case study explores the journey toward public performance; each offers a different angle on the role of resistance in the development of a performance, the juxtaposition of (and tensions between) which, it is hoped, will illuminate the idea of resistance as a creative performance tool.

Neil Heyde: Case Study 2

Towards the end of his life Fauré’s autographs regularly contain little or no indication of phrasing/articulation, and only broad or ‘rough’ indications of dynamics: this is in marked contrast to the published scores. The First Cello Sonata (1917) – the subject of this case study – is a striking example, and we find similar approaches in the 1920s in the Piano Trio and the String Quartet. This absence of markings is no accident or oversight, but a deliberate separation of working processes, as Fauré reveals on the autograph violin part for the Second Violin Sonata (1916), where he leaves a note indicating that the engraver should not set the slurs, but only the ties.31)The autograph is in F–Pn (Bibliothèque nationale, Paris), Mus., Ms. 22144 It is thus clear that Fauré explicitly planned to use a collaborative workshop setting to ‘finish’ his composition, working from the proofs.32)‘Finish’ is used here in both its English senses: as a literal completion of an incomplete process, and as the final ‘refinement’ stage(s) of a craft or manufacturing process. This distribution of the creative process, to which we must assume his string players would be expected to provide a crucial contribution, can be read in itself as a resistant strategy (breaking the ‘immediate’ connection between compositional idea and proposed realization) but the evidence of the workshop unpacked below reveals that this is just the first step. Perhaps this separation of processes does not sound particularly strange in the context of this article, but it is in notable contrast to almost all established art music practice in its institutionalizing of the workshop. Fauré undoubtedly had a very finely gauged and nuanced perception of the potential performance dimensions of these works – but, critically, it is one that he explicitly chooses not to realize prior to working with performers.

In the context of what appears to have been a gradual development of this system over the course of his life, I read Fauré’s increasing desire to employ what we have called, in response to Kurtág’s observation about the need for different kinds of resistances, ‘targeted solutions’.33)Fauré was a polygamous collaborator – partly as a natural consequence of his personality, but also, later, of the kinds of opportunities that were readily available through his contacts at the Conservatoire. Roy Howat’s critical edition of the Thème et variations op. 73 for piano [Edition Peters 7956] documents Fauré’s varied attempts to capture internal tempo relations and even the tempo of the theme itself, for which the indication ranges from Allegro molto moderato (Metzler, Germany, 1897) and Andante moderato (Hamelle, France, 1897) to Quasi Adagio (Hamelle, second edition, 1910). A less charitable reading of the situation might be that as Fauré grew busier and older (and more deaf), he became less interested in micro-managing performance details, relying on others to help him produce a finished score for publication. However, the evidence of the case study here indicates otherwise.

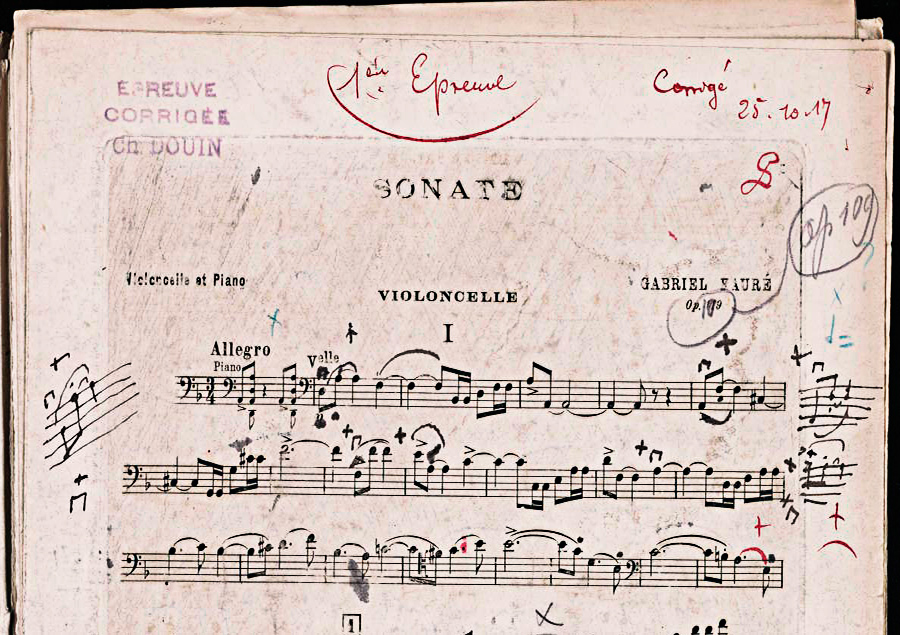

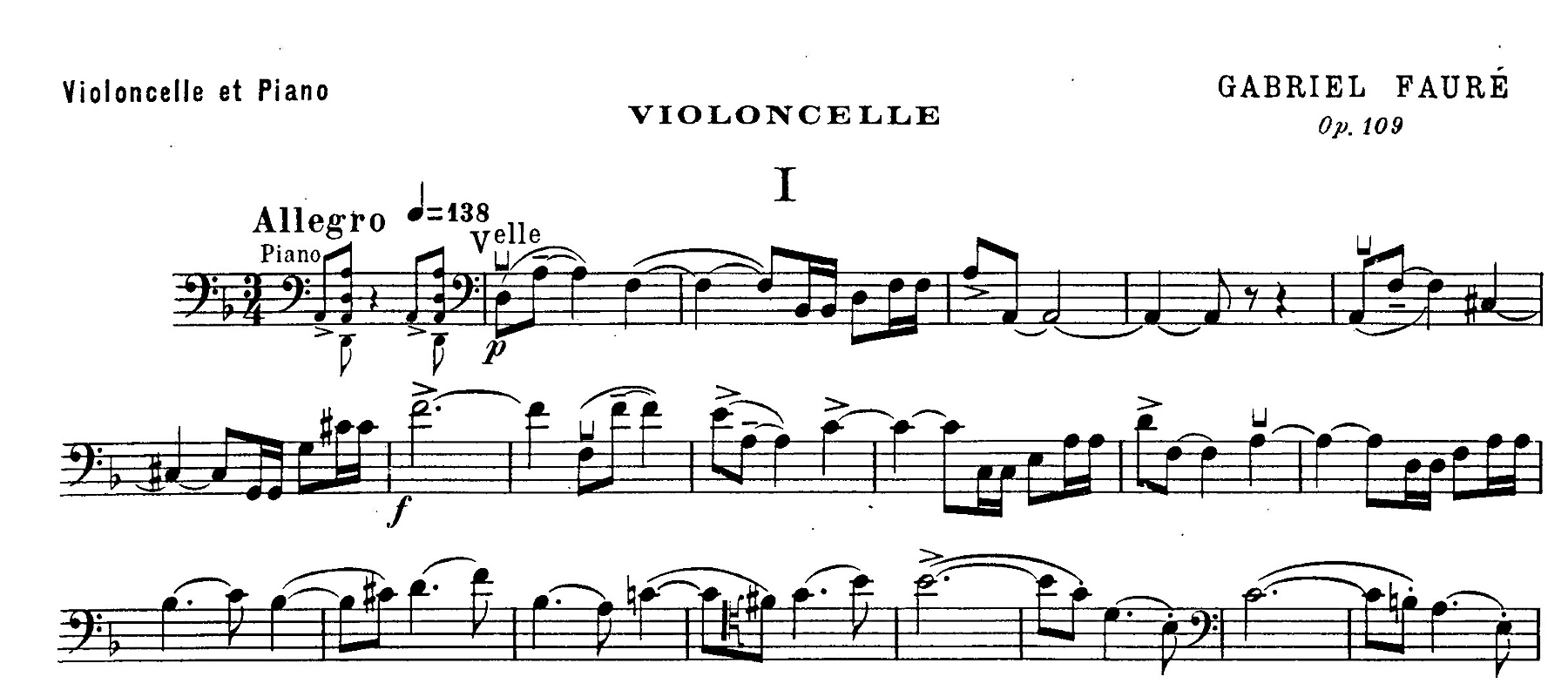

In exploring the first Cello Sonata, I consulted a number of sources. A complete autograph manuscript cannot be traced, but the New York Public Library houses a partial autograph, which is largely missing necessary information for the performer concerning phrasing and articulation, and has only very sketchy dynamic indications.34)US-NYp, JOG 72-116. This source includes a complete autograph of the last movement and a partial copy and autograph of the first movement. The Yale University Library holds corrected proofs for the whole sonata which have clearly also been used as the workshop copy (following the practice suggested by Fauré’s note on the Second Violin Sonata).35)US-NH, Gen. Mss. Music. Misc. (oversize folder 22). The engraving for the proofs is largely free of articulation markings, but the ‘corrections’ (see Figure 4 for a brief extract) are in fact extensive autograph additions and amendments, and there are cello fingerings and bowings that must have come directly from Gérard Hekking (who gave the premiere with Alfred Cortot). The editorial amendments in red are by Durand’s house editor Lucien Garban.

This case study focuses on the articulation issues concerning the principal theme of the first movement, which first appears in bar 2 in the cello.

In the piano, this is never slurred and there is never any articulation indicated on the offbeat quaver. In the cello, it is varied throughout the movement. Initially, we can see that both a slur and a staccato dot (along with a down-bow) have been added to these proofs. This articulation appears throughout the first subject (except on the second line – an omission, correct in the piano/cello score). The tied staccato dot is highly unconventional – that is, resistant, or actively opposing standard practice. Except for two bars later in the movement, in which the staccato may have been left as errors, the ‘rogue’ staccato dot is replaced in the first edition with a tenuto; presumably because the tenuto mark does not suggest a shortened ending and thus conflict with the tie:36)The contrasting bars can be found at rehearsal number 11 and four bars later. There is a third example in the score (but not in the cello part) nine bars after rehearsal number 11.

A tenuto is clearly not the same as a staccato, and offers a more conventional notational pairing with the tied note. Its replacement though raises the question: from what/where did the resistant notion of the staccato initially come? On the cello, it is a possible corollary of the D–A fifth and the ‘shared’ A with the open string, which picks up the resonance, and thus ‘holds’ the note. If this is set as the archetype for this phrase in the cello, every cellist will recognize the ‘carrying’ of the staccato (and its implicit ‘lift’) through into the next beat; and although this doesn’t make it easy to realize in performance, its potential is clear.

In itself, this is fascinating, but it is even more interesting to see the ways in which the articulation is played out across the course of the movement as a result of shifting musical priorities. For example, bar 12 (the penultimate bar of the second system in both examples) seems to have been left separate in order to organize the natural weight of a down-bow on the third beat, whilst the reappearance of the subject in the recapitulation (rehearsal number 7 in Figure 6) is entirely without slurs. This lends tremendous force to the higher register of the subject here (also marked forte), and responds to the instrument’s need for additional bow speed to support the full resonance in this register.37)The figure is also separate after rehearsal numbers 9 and 12, where the piano dynamic and inherent inertia of the C string generates an articulation challenge, and where the dot-slur ceases to generate possibilities and becomes counterproductive.

None of the foregoing examples, which are all tightly ‘targeted’ solutions, indicate anything actually ‘uncomfortable’, so my realization that the arrival of the accented forte F at bar 8 (during the initial iteration of the subject, see Figure 5) appears to have been engineered to be on an up-bow, came as a surprise. Such an approach seems at first glance to be unhelpfully resistant, and in my own performance copy of the score, I had immediately changed this bowing when first working on the piece. It was only in later experimentation with the reversed/uncomfortable bowing that I found it much more effective than my natural inclination to use a down-bow, as the increased physical work required to push out the forte increases the intensity of the sudden dynamic change and encourages a continued momentum into the next bar. This is, at least in part, the consequence of the increased physical resistance present in the act of producing the sound. My initial bowing strategy and the ‘resistant’ up-bow are shown in the two linked videos:

Video 1 Gabriel Fauré: Sonate op.109, first movement, opening. Initial verson.

Video 2 Gabriel Fauré: Sonate op.109, first movement, opening. Resistant version.

I propose that the distribution of experimentation evident in the materials explored here is a strategy of creative resistance. Fauré did not play the cello, and despite an extraordinary sensitivity to its capacities, he chose to use his inability fully to speak its vocabulary as a catalyst for the creative outcomes of the ‘finishing’ workshop. When I began work on this piece I did not realize to what extent this process had been undertaken, so I adopted a common policy of building a response to suit me and my particular instrument.38)This is a particularly common practice for instrumentalists who, more often than not, find themselves performing music written by composers who had no detailed firsthand knowledge of how to play the instrument. In the knowledge that Fauré was deliberately working in a way that could seem obstructive in order to target specific responses, I felt the need to begin again, with a forensic approach to building a bespoke vocabulary – a process of finding and making resistance in response to Fauré and his collaborators. This is aided by access to the corrected proofs, but is in no way dependent on it. Curiously, the second sonata, from 1921, was not handled in the same way, and a different kind of experimentation has been required. Fauré’s distinctive creative decision to institutionalize a workshop space in which what he was unable to access directly could be discovered thus provides a ‘site’ for exploring resistances that can be re-imagined by future performers. What is singularly striking about Fauré’s example is the clarity and systematic nature of his approach, and the potential for creative and technical richness that it demonstrates.

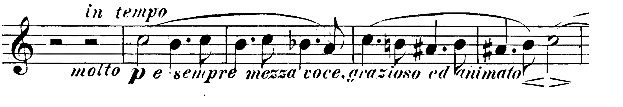

Olivia Sham: Case Study 3

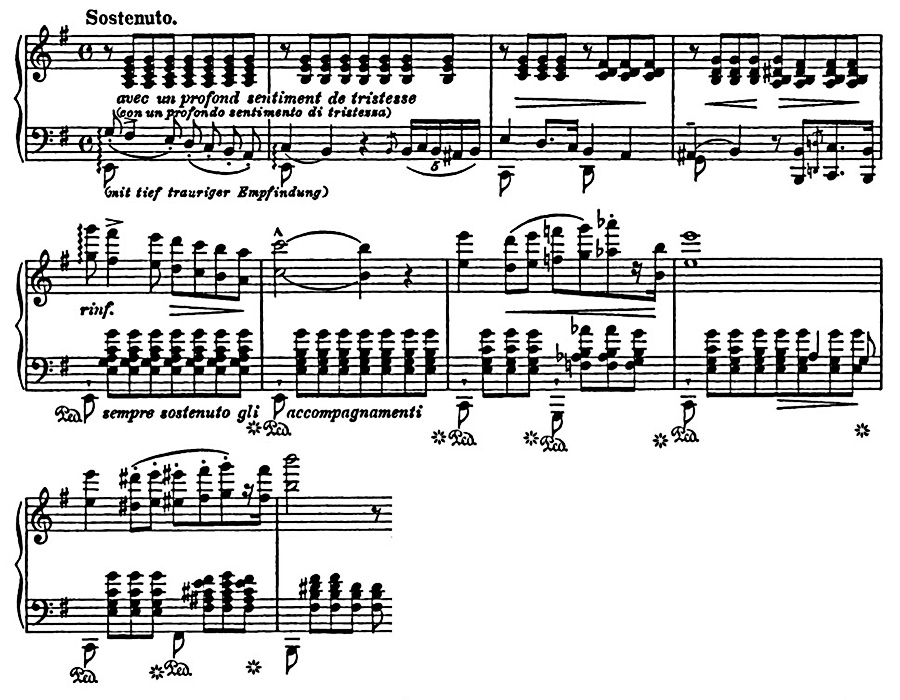

When preparing the revised version of the ‘Vallée d’Obermann’ from the first book of the Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage (1858) for solo piano, I found the absence of technical fireworks for much of the piece its most challenging aspect. After all, Liszt’s reputation as the greatest virtuoso pianist of the nineteenth century has led to conventional expectations of virtuosity in his compositions – virtuosity that pianists train to deliver. Here, then, the lack of the usual, crowded black note-heads leaves a blank-looking score which risks correspondingly literalist – and dull – performances. In experimenting with ways of performing this piece, I chose to explore compositional and performance traces left by Liszt, and the ways in which they overlapped, making resistances for myself that might help illuminate this notation. In particular, I made use of an earlier version of the piece, and historical pianos of the type that Liszt used. Such materials are traditionally viewed as mere curios – the ‘revised’ version ought to be superior, just as the modern piano’s technological progress supposedly renders historical instruments obsolete. However, I sought these out in the hope that the new obstacles I created could offer the potential to generate creative solutions.

The early version of the piece that first appeared as part of the Album d’un voyageur (1837–38) looks quite different on the page from the revised version of 1858. The first version is crowded with many more notes and a large quantity of expressive markings, both in comparison with the later version and with some of Liszt’s other contemporaneous pieces. Although this piece dates from his virtuoso years, Liszt scholar Dana Gooley has suggested that it was composed by Liszt in order to prove his skills as a composer, and was written in response to contemporary criticisms that he was ‘merely’ a performer.39)Dana Gooley, Virtuoso Liszt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 13. Liszt never performed the piece – perhaps explicitly in order to avoid any connection with his performing persona. Yet there is evidence that during this early period he was disturbed by the separation of his roles as composer and performer. He wrote in a public letter that:

[The] composer is necessarily forced to have recourse to inept or indifferent interpreters who make him suffer through interpretations that are often literal, it is true, but which are quite imperfect when it comes to presenting the work’s ideas or the composer’s genius.40)Letter to George Sand, 30 April 1837, printed in the Gazette musicale, 16 July 1837. See Franz Liszt, An Artist’s Journey, ed. and trans. by Charles Suttoni (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), p. 31.

Liszt’s discomfort with his separation of roles, and his decision not to play this piece in public, could explain why his notation here is particularly detailed: an attempt to substitute his own live performance by using markings to replicate it on the page; it implies an inability (or disinclination) to disconnect his performing and composing priorities. However, his attempt to capture the minutiae of his playing meant that he resorted to a profusion of markings that were unfortunately incapable of specifying the sort of multi-layered nuance for which he was famed. These include an experimental (though inconsistent) rubato system, ambiguous tempo directions and a surplus of articulation and accentuation that tends to draw the focus away from the fundamental melodic and harmonic material.

Certainly when I first read this version on a modern grand piano, the markings seemed more obstructive than illuminating. The resistance that arose in dealing with the inscrutable score of the later version was here replaced by another kind – a need to overcome the multiple demands of an excess of information. In engaging my years of pianistic training, I responded to this array of expressive indications with a default technical vocabulary that resulted in something that sounded, to my ears at least, overly mannered and artificial. Equally, the modern piano itself proved unyielding to the earlier notation, which had been configured in direct response not only to a particular (and extraordinary) player, but to a particular historical instrument and performance practice; and it provoked a sense of discomfort and tension in me that opposed the individualistic, expressive aims of the piece.41)As Liszt wrote in the preface to the Album d’un voyageur, music is capable of ‘expressing that within our souls which transcends the common horizon, all that eludes analysis, all that moves in hidden depths of imperishable desire and infinite intuition’.

I then attempted this early version on an instrument like one Liszt preferred at the time – an 1840 Érard grand piano.42)At the Royal Academy of Music, owned by Andrew Hunter Johnson. I had already been working on this instrument in other repertoire by Liszt, in particular the earlier works, so opting to try the ‘Vallée d’Obermann’ on it was perhaps an inevitable choice. Érard pianos were pioneering in piano technology, paving the way towards the modern grand piano. While studies on Érard pianos tend to focus on their radical innovations, e.g. the double escapement action at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the pianos continued to develop subtly over Liszt’s lifetime, especially in volume and sustaining ability. A notable difference thus exists between an instrument of the early 1840s and the late 1850s. For further details, see Olivia Sham, ‘Performing the Unperformable: Notions of Virtuosity in Liszt’s Solo Piano Music’ (doctoral thesis, Royal Academy of Music, 2014), in particular chapter 3. It should be further noted that in this case study, I am only examining one facet of the overlap between instrument and score – naturally, many others exist, not least in the way one deals with more conventionally ‘virtuosic’ textures. The differences were immediately evident. While on the modern piano a ‘conventionally musical’ rendition of the first subject sounded too meticulous and broken up (as a result of the particularities of the portamenti, articulation and phrasing), the historic instrument’s properties – and my own physical response to this – altered my perspective. The clarity of registration on the straight-strung instrument meant that the melody could project without being forced, and the immediacy of response in the shorter note decay as well as the physical closeness of the simpler action, meant that the details required less ‘effort’ to produce an audible result – which in turn meant that they sounded less mannered and exaggerated. The more blended sonority also aided this. The details thus became subsumed to a level that did not aim to be noticeably ‘audible’, but nevertheless indicated the sort of nuanced playing fundamental to a virtuoso performer like Liszt (Video 3). While I still found that the notation imposed a resistant attention to detail in musical expression, the historic instrument made it easier to explore the creative possibilities inherent in this.43)According to the diaries kept by Madame Auguste Boissier recording the lessons Liszt gave her daughter in 1831–32, Liszt said that ‘the same nuances, expressions, and modifications must not be repeated … for this is tiresome’. 20 March, 1832. See Auguste Boissier, The Liszt Studies: Essential Selections from the Original 12-Volume Set of Technical Studies for the Piano including the first English edition of the legendary Liszt Pedagogue, a lesson diary of the master as teacher, as kept by Mme. Auguste Boissier, 1831–32, trans. and ed. by Elyse Mach (New York: Associated Music Publishers, 1973), xxiv.

Video 3 Franz Liszt: Album d’un voyageur, Book 1 no. 4, ‘Vallée d’Obermann’ S.156/5, bars 23–32. Live performance on 7 March 2013 in the Piano Gallery, Royal Academy of Music.

As a result of this exploration, I came to realize that Liszt’s modified notational practice in the revised version (1858) might be seen as indicative of his desire to stimulate the creativity of other performers (as he himself had retired from the concert stage). In 1856 he wrote:

I cannot conceal from myself that much, and that perhaps the most important, cannot be set forth on paper.44)Franz Liszt, Franz Liszt’s Musikalische Werke, Serie I (Symphonische Dichtungen), Band I, ed. Otto Taubmann (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1907), Introduction.

The ‘emptier’ score defies any sense that it can simply be reproduced, and as Liszt wrote of the virtuoso in 1859:

The virtuoso is not a mason; who … constructs the poem which the architect has already designed upon the paper. He is not a passive instrument, reproducing the thoughts and feelings of others whilst adding nothing of his own. He is not a reader, more or less expert, delivering a text; without marginal notes or glossary, and requiring no interlinear commentary.45)Franz Liszt, The Gipsy in Music, trans. Edwin Evans (London: William Reeves, 1926), p. 265.

As such, although the first subject of the revised version can appear bland on the page, with only slight detailing, this did not render unnecessary the level of nuance I had developed in performing the piece on a contemporaneous instrument; instead, I took it as an incentive for me to explore new vocabularies for presenting the piece on modern piano.

Figure 8 Franz Liszt: Années de pèlerinage, Première année: Suisse, no. 4 ‘Vallée d’Obermann’ S.160/6, bars 1–8.

Alongside my previous explorations, I was guided by the more sophisticated harmonic writing of the later version to experiment outside my default toolbox, with a less uniformly legato ‘expressive’ touch, rhythmic fluctuations, colouring, and voicing, aided by slight dislocations of hands and chords (Video 4).

Video 4 Franz Liszt: Années de pèlerinage, Première année: Suisse, no. 4 ‘Vallée d’Obermann’ S.160/6, bars 1–8. Live performance on 7 March 2013 in the Dukes Hall, Royal Academy of Music, London.

Indeed, embracing both versions and instruments was not an attempt to find Liszt’s definitive ‘Vallée d’Obermann’: it was a way for me to find my own personal way into the piece.46)Other influences, such as the weight of the performance tradition of the later version and my reaction to this, has not been explored here. In trying to explore the resistances posed by an earlier score and instrument, I was able to destabilize my relationship with the seemingly impenetrable aspects of the later version on modern piano. The second version also helped me perform the first, by clarifying musical priorities that might otherwise have been obscured by the density – both of expressive markings and notes – of the score’s appearance. In comparing the resistances I found in each of the instruments and scores, I was made aware of the nature of the creative responsibility I needed to take. I thus used my reactions to such resistances to force me from trained, instinctive responses into finding creative ways to perform ‘the’ piece.

Sarah Callis: Case Study 4

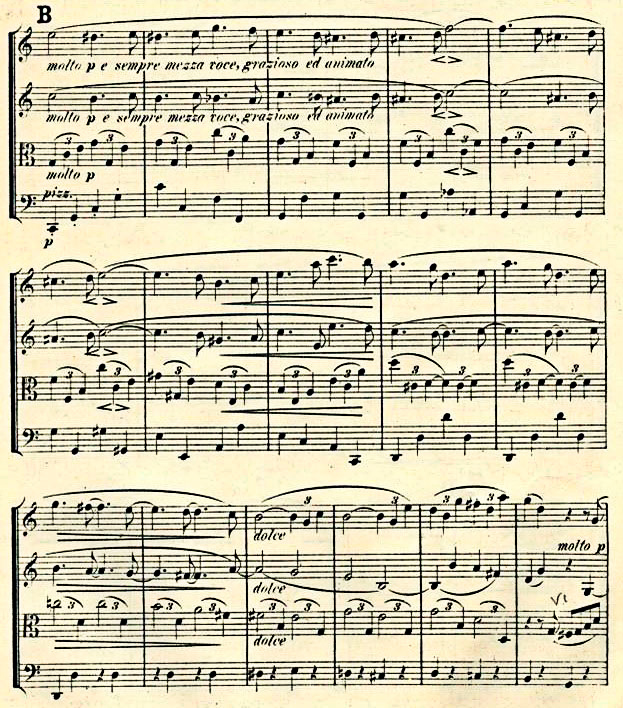

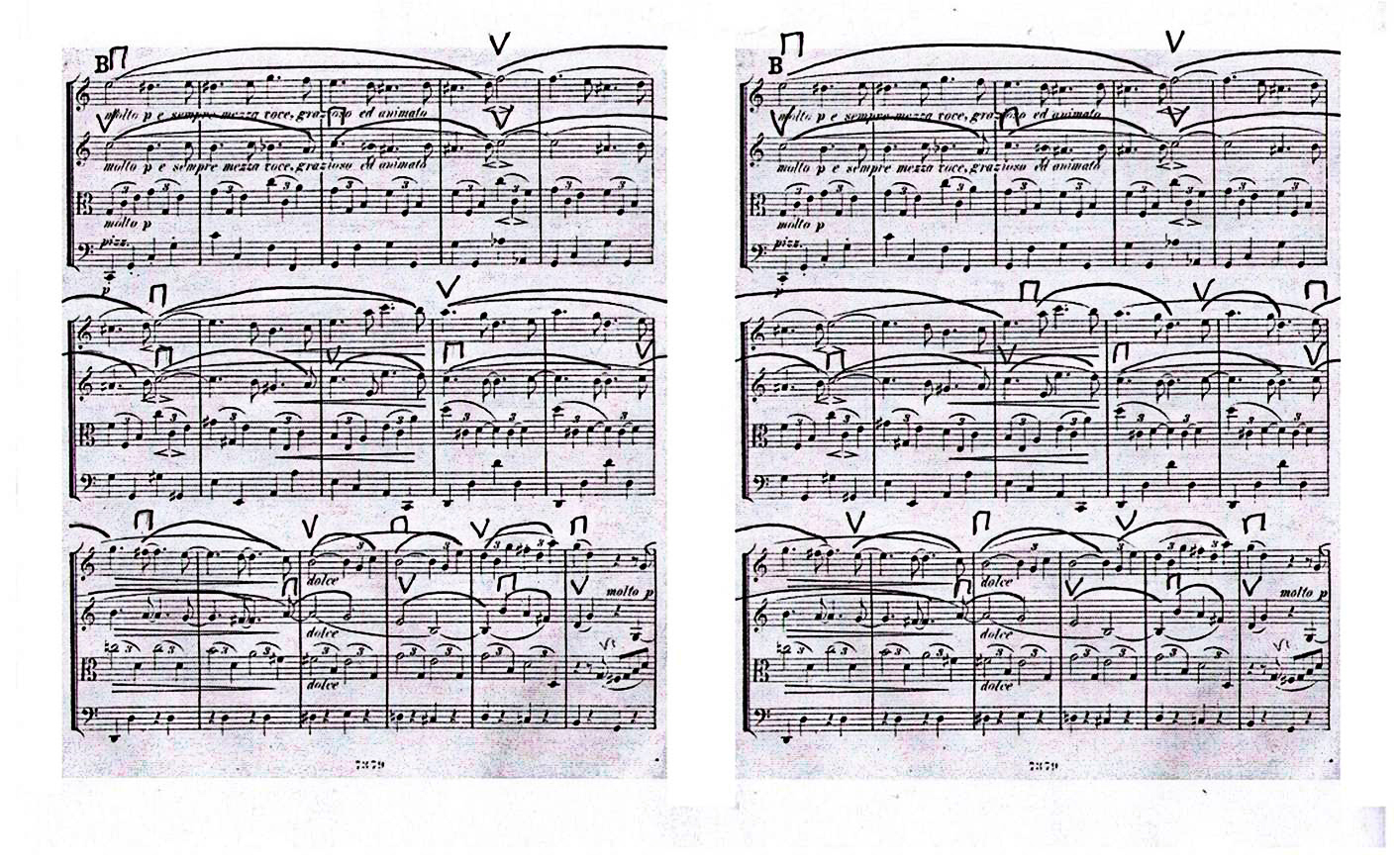

This case study explores the process of artistic investigation undertaken by the Kreutzer Quartet (Peter Sheppard Skærved, Mihailo Trandafilovski, Morgan Goff and Neil Heyde) in their programming of Brahms’s op. 51 string quartets. Unlike the other case studies, here I was a third party in the performance process, documenting the performers’ investigations by filming an extended rehearsal-workshop (including discussion with the players), and subsequently responding to the evidence it provided. I aim to capture the Kreutzer’s creative process by presenting a detailed analysis of their approach to one particular theme – the second subject of the first movement of op. 51 no. 2 in A minor (Figure 9). The study also involves an examination of Brahms’s revision of his manuscript during workshop performances with the Walter Quartet (Joseph Walter, Franz Brückner, Anton Thoms and Hippolyt Müller) in 1873. The Kreutzer’s decision to programme the op. 51 quartets together (usually separated in concerts, presumably because of the intense and difficult minor-key rhetoric they share), allowed them to become deeply immersed in Brahms’s particular language. However, it also made it necessary to develop performance tools to target the specificity of each expressive idea as a means of sustaining an hour of Brahms’s most challenging music; the Quartet’s treatment of this theme is an example of their approach.

Figure 9 Johannes Brahms: String Quartet op. 51 no. 2, first movement, bars 46–61. First Edition (1873).

This theme may not seem immediately problematic, offering at first glance a lilting, lyrical melody in sonorous thirds with a stable accompaniment, apparently designed to provide respite from the melancholy intensity of so much of the rest of the two quartets. Notable, however, is the expression marking, which – unusually for Brahms – stipulates dynamic, tone quality, character and tempo, a level of detail he did not commonly employ. The manuscript suggests that Brahms was exploring his expressive idea during trial performances with the Walter Quartet in what was effectively a composer–performer workshop scenario.47)These took place in Munich, where the Walter Quartet was based, in the early summer of 1873. In her detailed discussion of Brahms’s manuscript for the New Brahms Edition, Salome Reiser notes that Brahms ‘modified the tempo and expression markings many times’.48)Salome Reiser, ed., Johannes Brahms Streichquartette (München: G. Henle Verlag, 2004), p. 175. The following example from the only surviving manuscript shows some of these modifications (Figure 10).

Figure 10 Johannes Brahms: String Quartet op. 51 no. 2, first movement, bars 46–49. Autograph Manuscript, 1873. Reproduced with permission of the Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien, Signatur: A 139.

This process of revision was settled for the first edition (see Figure 9). Interestingly, despite a number of repetitions of this melody during the movement, this marking is never repeated in exactly the same way, and there are discrepancies between score and parts in both expression and phrase markings. With reference to the editing of parts, when preparing the First Symphony Brahms wrote to his editor Robert Keller, ‘you will recognize as intentional certain discrepancies that may occur, especially with regard to performance indications’.49)George Bozarth, ed., The Brahms–Keller Correspondence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), p. 3. Such a comment can be seen as an invitation to performers to examine the differences in his scores with care.

What might the evidence of these materials suggest to a performer today? Might they be interpreted as evidence of friction between notation and idea – Brahms’s struggle to reconcile the Walter Quartet’s performance with what he had originally imagined? Was he refining his expression markings in order to close the gap between what he was hearing and what he had intended? In this case study, I observed that the tensions in Brahms’s notation were seen by the Kreutzer Quartet not as an attempt to close a gap, but rather as a way of leaving his music open for the players to negotiate; the diversity of implications in the markings across score and parts offered a source of found resistance through which they could explore the rhetorical possibilities of this apparently ‘simple’ melody. Brahms’s original biographer Max Kalbeck described this theme as a ‘part-striding, part-sliding dance-song … cheerful and delicately-woven …’, vividly capturing its multi-layered potential.50)Max Kalbeck, Johannes Brahms, 4 vols (Berlin: Deutsche Brahms-Gesellschaft, 1921), II, p. 448. My translation.

In exploring this theme the Kreutzer’s attention was drawn in particular to the phrase markings, and how they opened up the expressive possibilities of bowings. They noted that in the opening phrase, although both the score (see Figure 9) and the first violin part (Figure 11a) showed a 4-bar phrase marking, in the second violin part (Figure 11b) it has been divided into two.

Figure 11a Johannes Brahms: String Quartet op. 51 no. 2, first movement, bars 46-50. First Edition, violin 1 part.

Figure 11b Johannes Brahms: String Quartet op.51 no.2, first movement, bars 46-50. First Edition, violin 2 part.

This suggested that, as well as indicating the phrase structure of the theme, the markings in the parts might also have been treated as bowings. Certainly this degree of bow sustaining in the first violin could trigger a real piano mezza voce – to which the other parts could respond – as well as activate the need for animato in order to execute the whole phrase in a single bow-stroke. But it also sets up a creative tension with the theme’s enticement to sing, as generated by the character and texture of the thematic material itself and its potential as a moment of expressive reprieve. When the phrasing is treated as bowing – arguably an act of making resistance – the technical demands of the approach destabilize the first violinist’s relationship with technique and instrument (in the manner advocated by Evens) and intensify the process of exploration. Indeed his instrument, the 1698 ex-Joachim long-pattern Strad, offers immense scope for the exploration of sustained bowing; and as a result of their extensive experience of collaborating with composers, the Quartet have come to expect the need to negotiate the technical implications of any notation.51)For example, Amanda Bayley has documented the Quartet’s work with Michael Finnissy in a number of publications. See, e.g., Amanda Bayley and Michael Clarke, Evolution and collaboration: the composition, rehearsal and performance of Finnissy’s Second String Quartet, Software DVD (Lancaster: PALATINE, 2011).

During the rehearsal-workshop, the Quartet played the movement three times, and in each statement of the exposition theme, the first violinist played, as planned, the opening phrase in a single bow. However, they did not subsequently treat the theme’s phrase marks as a blueprint for bowing; indeed, the four-bar phrase at the dynamic peak of the melody (bars 54–57) pushed hard against the technical viability of this approach – the resistance threatening to spill over – and I observed that each performance became subject to its own unique momentum. In analysing the performances on film, it seemed to me that the long opening bowing set up a specific energy that propelled each version forward in distinctive ways, and always ‘in the moment’ of performance.

Figure 12 transcribes two examples of the bowing patterns that emerged in this workshop, both of which created alternative counterpoints with the consistent bowing pattern of the second violinist.

Figure 12 Johannes Brahms: String Quartet op. 51 no. 2, first movement, bars 46–61. First Edition (1873), with bowings added.

The differences arise from the length of each bow-stroke, the emergence of similar or contrary motion bowings, and from staggered or matched bow changes – changes that draw out both the down- and up-beat potential of the theme. These inflections are immensely subtle, indeed often inaudible, since a bow change may or may not be articulated. But this is not the point: it is the choreography of the bowing that provides the performers with a means to actively invent the theme at each turn, the tool for crafting their expressive idea. In this sense, what we could call ‘the resistant bowing’, allowed the Kreutzer Quartet to activate their own particular demands on the materials in a manner that was both planned and immediate, both a response to and a claim upon the potential of the musical material. The ‘understated’ result is a reminder of Sennett’s assertion that ‘simplicity represents a goal in craftwork … but to make difficulties where none need be is a way to think about the nature of soundness’.52)Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 225.

(Video 5).

Video 5 Johannes Brahms: String Quartet op. 51 no. 2, first movement, bars 46–61; the Kreutzer Quartet demonstrating two examples of bowing patterns.

Conclusions

In his discussion of the ‘sites of resistance’, Sennett – borrowing models from natural ecology – draws a distinction between a boundary which ‘can be a guarded territory’ or ‘simply an edge where things end’, and what we have already called a border, which ‘by contrast, is a site of exchange where organisms become more interactive’. He goes on to emphasize that ‘the border is an active edge’ (or ‘live edge’) and is therefore ‘the more productive environment for working with resistance’.53)Sennett, The Craftsman, pp. 227–31. This emphasis on action is vital for our view of creative resistance – its role in the case studies is never passive or static, but always individually configured and dynamic.

An active edge is by definition a point of interface – a ‘site of exchange’ – and requires the meeting of two different environments. According to Sennett, as well as being porous, a border ‘resists indiscriminate mixture; it contains differences’.54)Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 227. In the case studies discussed here, borders – and the ‘differences’ they separate – are constructed in a number of ways, perhaps most notably at the interfaces between notations and the response of the instrument and player. What is very clear is that in each case, a productive border must offer the player a valid site of response, one to which they can fully commit. For example, Heyde detects in Fauré’s workshop notation evidence of Hékking’s physical relationship with his instrument, so that for Heyde, the resistance that he identifies in the score gains authority, impacting upon his own creative response to the music. Sham’s interface with the Érard, and its role in her grasp on Liszt’s notation is similarly visceral and alive, as is the border the Kreutzers construct between Brahms’s markings and the capacities of the bow. David Young captures the important metaphysical aspect of this in his comment to Kanga that ‘the more you are convinced that what you’re doing relates to the painting … the better it will work’.55)Kanga, Inside the Collaborative Process, p. 422. However, there are also pragmatic and physical sides to this: in each case study, constructing live edges – between materials, instruments, players, composers – offers sites where resistance can become an efficient and practical tool for the making and remaking of musical works.

The idea of a live edge also points to the conceptual usefulness of identifying resistances as both found and made. After all, the distinction could be misleading – proposing two discrete activities rather than the interactive and dynamic process described above: Fauré’s resistant dot/tie notation, for example, was clearly ‘found’, and Kanga’s spreadsheet of timings deliberately ‘made’. Critically, however, in our understanding of creative resistance finding and making are always folded in upon one another in a reciprocal and mobile relationship: to consider a notation in any form (and from any point in its life), and to grapple with its details, is both to ask questions and find answers – both to observe and claim it – within a creative loop of experimentation that is driven by each player’s instrument and technique. In fact, finding and making cannot be separated – the two belong to a single, active process of invention through which a performer can gain a grip on a musical idea. But crucially what ‘found and made’ points to is the push and pull of this process, a reminder that the fluid and exploratory nature of employing resistance we have described is never arbitrary, but requires the construction of an integrative space generated by full commitment to materials, techniques and instruments. Kurtág reminds us of this – that resistance can be a tool for getting ‘into the heart of the piece’, a means of activating the distribution of the creative process such that works can be made and remade in an ongoing regenerative process.

Footnotes

References

| ↑1 | Tate Britain, Richard Deacon (London, 5 February – 27 April 2014). Richard Deacon (b. 1949) is a leading British artist, best known for his abstract sculptures drawn from extensive exploration and manipulation of a wide range of different materials. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Richard Deacon, ‘Interview with Mark Lawson’, Front Row 3 February, BBC Radio 4 http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01rp2v5, at 24:43. Accessed 15 July 2014. |

| ↑3 | Susan Holtham, ‘Work of the week: After by Richard Deacon’, Tate Blogs, 5 February 2014 http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/blogs/work-week-after-richard-deacon. Accessed 15 July 2014. |

| ↑4 | Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), p. 225. |

| ↑5 | Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 226. |

| ↑6, ↑52 | Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 225. |

| ↑7 | Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 225 |

| ↑8 | György Kurtág, Three Interviews and Ligeti Homages, compiled and ed. by Bálint András Varga (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2009), p. 30. |

| ↑9 | Kurtág, Three Interviews, p. 31. |

| ↑10 | Rachel Beckles Willson describes a particularly acute example of Kurtág’s individualized use of resistance in relation to a performance of Samuel Beckett: What is the Word performed by the singer Ildikó Monyók at the Royal Academy of Music in 2002. Kurtág’s demanding approach to his performers is legendary. Rachel Beckles Willson, ‘A study in geography, “tradition”, and identity in concert practice’, Music and Letters 85/4 (2004), pp. 602–13, here 608–9. |

| ↑11 | Artur Schnabel, Music and the Line of Most Resistance (New York: Da Capo, 1969 [originally published 1942]), p. 62. |

| ↑12 | Leon Botstein argues persuasively that Schnabel’s rhetoric was constructed in response to the excesses of Romantic virtuosity (p. 588) and that his uncompromising philosophy of creative struggle, when separated from the man himself, had a ‘paralyzing’ effect on the next generation (p. 593). See Leon Botstein, ‘Artur Schnabel and the Ideology of Interpretation’, Musical Quarterly, 85/4 (2001), pp. 587–94. |

| ↑13 | Artur Schnabel, ed., 32 Sonatas for the Pianoforte: Ludwig van Beethoven (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1935), Editor’s Preface. |

| ↑14 | For example, in Beethoven’s op. 10 no. 3, 2nd movement, bar 43, Schnabel opts to play the sf B flat with a thumb, which seems an awkward choice considering the position of the note at the top of the phrase. However, the time taken to reach the note with the thumb is clearly designed to have a significant expressive effect, and it also enriches timbre and volume. Schnabel reinforces his idea by adding a rubato. |

| ↑15 | Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 225. |

| ↑16 | Aden Evens, Sound Ideas: Music, Machines and Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), p. 153. Evens is discussing the work of improvisers, in particular John Corbett, but this quote is equally relevant to the performance of notated music. |

| ↑17 | See Liza Lim, ‘A mycelial model for understanding distributed creativity: collaborative partnership in the making of ‘Axis Mundi’ (2013) for solo bassoon’, University of Huddersfield Repository, http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ (Lim, 2013) for an exploration of the creative de-stabilization of the interface between players and the sound they produce. |

| ↑18 | Sennett, The Craftsman, pp. 227 and 231. |

| ↑19 | The effects of resistance, as well as other catalysts and pressures, on composer–performer collaborations are explored in detail in Zubin Kanga, Inside the Collaborative Process: Realising New Works for Solo Piano (PhD, Royal Academy of Music, 2014); see Chapter 5 for a detailed examination of David Young’s Not Music Yet. |

| ↑20 | Zubin Kanga’s post-doctoral position in the CTEL research centre at the University of Nice-Sophia Antipolis is part of the GEMME project on Music and Gesture, supported by funds granted by the ANR (National Agency for Research, France). |

| ↑21 | Young’s approach to collaborating around graphic notation has developed over many years of collaborations with solo performers such as pianists Mark Knoop and Michael Kieran Harvey; percussionist Eugene Ughetti; clarinettists Carl Rosman and Richard Haynes; and ensembles including Elision (Australia/UK), Ensemble Offspring (Australia), Ives Ensemble (Netherlands), Champ d’Action (Belgium), Ensemble 2000 (Denmark), Manufacture Ensemble (Japan) and Æquator (Switzerland). His largest scale work using graphic notation is his opera cycle, The Minotaur Trilogy (composed with Margaret Cameron), performed by Chamber Made Opera (Australia) in 2012. |

| ↑22 | Young: Not Music Yet (2012). Preface. |

| ↑23 | Earle Brown’s December 1952 is a classic example of an abstract graphic score intended as a focus for the performer’s imagination rather than a schematic. Cage’s graphic scores include his Concert for Piano and Orchestra (1958), which plays with different types and degrees of abstraction on each page. In both cases, the specific approach to interpreting the notation is not specified, in contrast with Young’s approach. |

| ↑24 | Deborah Hay was born in Brooklyn. After training and working with Merce Cunningham in the 1960s, she moved to Austin, Texas, where she developed her own unique approach to choreography. In the last 20 years, her work has received numerous international prizes and has been performed across the US, Europe and Australia. |

| ↑25 | Kanga, Inside the Collaborative Process, p. 393, |

| ↑26 | To some extent, we were confirming Ferneyhough’s assertion that notation expresses ‘an implied ideology of its own process of creation’. See Brian Ferneyhough, ‘Aspects of Notational and Compositional Practice’, in James Boros and Richard Toop, eds., Collected Writings (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic), pp. 2–13, here 4. |

| ↑27 | The quotes in this paragraph are from Kanga, Inside the Collaborative Process, pp. 416–422. |

| ↑28 | For further discussion of the collaborative creation of Not Music Yet, see Zubin Kanga, ‘“Not Music Yet”: Graphic Notation as a Catalyst for Collaborative Metamorphosis’, Eras Journal, Edition 16, 2014. |

| ↑29 | Joseph Szigeti, Szigeti on the violin (New York: Dover, 1979), xxi–xxii. |

| ↑30 | Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 221. |

| ↑31 | The autograph is in F–Pn (Bibliothèque nationale, Paris), Mus., Ms. 22144 |

| ↑32 | ‘Finish’ is used here in both its English senses: as a literal completion of an incomplete process, and as the final ‘refinement’ stage(s) of a craft or manufacturing process. |

| ↑33 | Fauré was a polygamous collaborator – partly as a natural consequence of his personality, but also, later, of the kinds of opportunities that were readily available through his contacts at the Conservatoire. Roy Howat’s critical edition of the Thème et variations op. 73 for piano [Edition Peters 7956] documents Fauré’s varied attempts to capture internal tempo relations and even the tempo of the theme itself, for which the indication ranges from Allegro molto moderato (Metzler, Germany, 1897) and Andante moderato (Hamelle, France, 1897) to Quasi Adagio (Hamelle, second edition, 1910). |

| ↑34 | US-NYp, JOG 72-116. |

| ↑35 | US-NH, Gen. Mss. Music. Misc. (oversize folder 22). |

| ↑36 | The contrasting bars can be found at rehearsal number 11 and four bars later. There is a third example in the score (but not in the cello part) nine bars after rehearsal number 11. |

| ↑37 | The figure is also separate after rehearsal numbers 9 and 12, where the piano dynamic and inherent inertia of the C string generates an articulation challenge, and where the dot-slur ceases to generate possibilities and becomes counterproductive. |

| ↑38 | This is a particularly common practice for instrumentalists who, more often than not, find themselves performing music written by composers who had no detailed firsthand knowledge of how to play the instrument. |

| ↑39 | Dana Gooley, Virtuoso Liszt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 13. |

| ↑40 | Letter to George Sand, 30 April 1837, printed in the Gazette musicale, 16 July 1837. See Franz Liszt, An Artist’s Journey, ed. and trans. by Charles Suttoni (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), p. 31. |

| ↑41 | As Liszt wrote in the preface to the Album d’un voyageur, music is capable of ‘expressing that within our souls which transcends the common horizon, all that eludes analysis, all that moves in hidden depths of imperishable desire and infinite intuition’. |

| ↑42 | At the Royal Academy of Music, owned by Andrew Hunter Johnson. I had already been working on this instrument in other repertoire by Liszt, in particular the earlier works, so opting to try the ‘Vallée d’Obermann’ on it was perhaps an inevitable choice. Érard pianos were pioneering in piano technology, paving the way towards the modern grand piano. While studies on Érard pianos tend to focus on their radical innovations, e.g. the double escapement action at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the pianos continued to develop subtly over Liszt’s lifetime, especially in volume and sustaining ability. A notable difference thus exists between an instrument of the early 1840s and the late 1850s. For further details, see Olivia Sham, ‘Performing the Unperformable: Notions of Virtuosity in Liszt’s Solo Piano Music’ (doctoral thesis, Royal Academy of Music, 2014), in particular chapter 3. It should be further noted that in this case study, I am only examining one facet of the overlap between instrument and score – naturally, many others exist, not least in the way one deals with more conventionally ‘virtuosic’ textures. |

| ↑43 | According to the diaries kept by Madame Auguste Boissier recording the lessons Liszt gave her daughter in 1831–32, Liszt said that ‘the same nuances, expressions, and modifications must not be repeated … for this is tiresome’. 20 March, 1832. See Auguste Boissier, The Liszt Studies: Essential Selections from the Original 12-Volume Set of Technical Studies for the Piano including the first English edition of the legendary Liszt Pedagogue, a lesson diary of the master as teacher, as kept by Mme. Auguste Boissier, 1831–32, trans. and ed. by Elyse Mach (New York: Associated Music Publishers, 1973), xxiv. |

| ↑44 | Franz Liszt, Franz Liszt’s Musikalische Werke, Serie I (Symphonische Dichtungen), Band I, ed. Otto Taubmann (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1907), Introduction. |

| ↑45 | Franz Liszt, The Gipsy in Music, trans. Edwin Evans (London: William Reeves, 1926), p. 265. |

| ↑46 | Other influences, such as the weight of the performance tradition of the later version and my reaction to this, has not been explored here. |

| ↑47 | These took place in Munich, where the Walter Quartet was based, in the early summer of 1873. |

| ↑48 | Salome Reiser, ed., Johannes Brahms Streichquartette (München: G. Henle Verlag, 2004), p. 175. |

| ↑49 | George Bozarth, ed., The Brahms–Keller Correspondence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), p. 3. |

| ↑50 | Max Kalbeck, Johannes Brahms, 4 vols (Berlin: Deutsche Brahms-Gesellschaft, 1921), II, p. 448. My translation. |

| ↑51 | For example, Amanda Bayley has documented the Quartet’s work with Michael Finnissy in a number of publications. See, e.g., Amanda Bayley and Michael Clarke, Evolution and collaboration: the composition, rehearsal and performance of Finnissy’s Second String Quartet, Software DVD (Lancaster: PALATINE, 2011). |

| ↑53 | Sennett, The Craftsman, pp. 227–31. |

| ↑54 | Sennett, The Craftsman, p. 227. |

| ↑55 | Kanga, Inside the Collaborative Process, p. 422. |