Visualizing Visions

The Significance of Messiaen’s Colours

Table of contents

DOI: 10.32063/0201

Håkon Austbø

Pianist Håkon Austbø is a Professor at the Norwegian Academy of Music, formerly Stavanger and Amsterdam, widely known for his work with composers such as Messiaen and Skryabin. In 1971, he won the Olivier Messiaen Competition, and in 2013 was made Knight of the French l’Ordre National des Arts et des Lettres.

The project ‘Messiaen’s Colours’ was conducted at the Norwegian Academy of Music (NAM) as part of the broader research project ‘The co-creative musician’, led by Magnus Andersson. The preliminary stage of the project was devoted to a performance of the Trois Petites Liturgies de la Présence Divine at the closing concert of a Messiaen festival organised by the group. The musical part of this performance requires a female choir, a string orchestra of specific size, various percussion instruments including celesta, and, beside the piano solo part, an ondes martenot solo that is essential to the colouring of the piece. Valérie Hartmann-Clavérie played this on the ondes martenot. In addition to playing the piano solo part, Håkon Austbø, the author of this article, undertook the development of colour projections. The resulting colour part, to be played from an electronic keyboard, was performed at the concert by the pianist Sanae Yoshida. With the collaboration of the Oslo Sinfonietta, conducted by Christian Eggen, and the Norwegian Soloist Choir with conductor Grete Pedersen, an ensemble of students and professionals was put together. This turned out to be the first performance of this piece in Norway and took place at the Norwegian Academy on 28 February 2013.

The project was ultimately aimed at realizing a colour part for the gigantic piano cycle Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus. This cycle was performed on 10 August 2013, at the Jakob church in Oslo, in the framework of the Oslo International Chamber Music Festival. Again, Håkon Austbø played the piano and prepared the colour part, which was again performed by Sanae Yoshida. During the whole project, Ricardo del Pozo provided expertise on the software environment as well as on the artistic content.

by Håkon Austbø

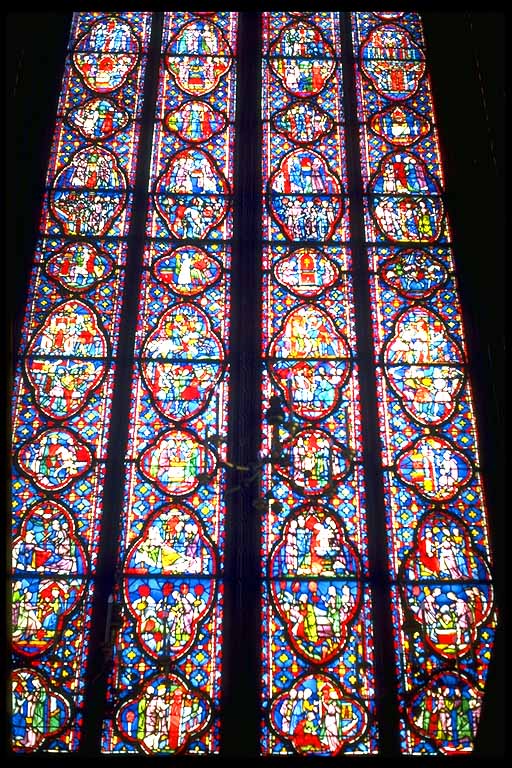

Music + Practice, Volume 2

Scientific

What does a rose-window in a cathedral do? It teaches through imagery, through symbolism, through all the characters that inhabit it – but what most catches the eye are its thousand spots of colour which ultimately dissolve into a single, very pure shade, so that someone looking on says only, ‘That window is blue’, or ‘That window is violet.’ I had nothing more than this in mind.1)Olivier Messiaen, Traité de rythme, de couleur et d’Ornithologie (1949–1992), 7 vols. (Paris: A. Leduc, 1994–2002), vol. 7, p. 198: ‘Que fait une rosace de cathédrale? Elle enseigne par l’image, par le symbole, par tous les personnages qui la peuplent – mais surtout elle frappe l’œil par des milliers de taches de couleurs, qui, finalement, se résume en une seule couleur très simple, à tel point que celui qui contemple dit seulement: cette rosace est bleue – ou: cette rosace est violette… Je n’ai pas voulu faire autre chose…’ English translation by Matthew Schellhorn, in Christopher Dingle and Nigel Simeone, eds, Olivier Messiaen: Music, Art and Literature (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), p. 39 (emphasis added).— Olivier Messiaen / Olivier Messiaen

Video 1 Olivier Messiaen: ‘Regard du Silence’ (Vingt Regards, no. 17), excerpt. Performed at the Jakob Church of Culture, Oslo, 10 August 2013.

Anyone familiar with Olivier Messiaen’s music knows that his scores often contain names of colours. In his Traité de rythme, de couleurs, et d’ornithologie (vol. 7), the composer elaborates on how the colours correspond to scales and chords. After more than 40 years of performing Messiaen’s music worldwide, there was still one thing neither I nor anyone else had done: to present the audience with these colours in a live performance. It was the aim of my project to visualize these, and an example of how this turned out is given right away:2)See Appendix 1 for details on this video.

Video 1 shows an excerpt from my performance of the complete Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus, a piano cycle consisting of 20 movements, with a total duration of more than two hours. Concert performances with colour displays of this cycle as well as of the Trois Petites Liturgies de la Présence Divine, were end results of the project conducted at the Norwegian Academy of Music (see separate box), but, needless to say, the work drew on experience and knowledge gained over a much longer period of time.

How can Messiaen’s scores be translated to colour projections, and how can the technical demands be met to control these in a live performance? I address these questions in what follows.

Messiaen and synaesthesia

3)The author wants to thank Christina Kobb for her extensive and excellent work in editing this article.

Already as a young boy, Olivier Messiaen was fascinated by colours. At the tender age of 10, he marvelled at the stained-glass windows at the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris – a somehow mystical experience which ‘marked him for life’.4)Olivier Messiaen, Traité de rythme, de couleurs, et d’ornithologie, vol. 7, p. 7. (Paris: Alphonse Leduc, 2002). A decade later, the experience of meeting the Swiss artist Charles Blanc-Gatti – who apparently painted the sounds he heard from an organ – made a profound impact and intensified Messiaen’s earlier impressions of the connections between colours and sounds:

And I realized that I also connected colours to sounds, but intellectually, not with the eyes. In fact, when I hear or read music, I always see colour complexes in my mind that go with the sound complexes.5)Messiaen, Traité, vol. 7, p. 7: ‘Et je me suis rendu compte que, moi aussi, je liais des couleurs aux sons, mais intellectuellement, pas par les yeux. En effet, depuis toujours, lorsque j’entends ou lorsque je lis de la musique, je vois dans ma tête des complexes de couleurs qui marchent et bougent avec les complexes de sons’.

As I had the privilege of working with Messiaen on and off from 1970 until his death in 1992, I was soon confronted with his perception of ‘sound complexes’ matching up with ‘colour complexes’. The stained-glass windows of his childhood remained an inspiration to him, and he wanted certain of his works to be performed in the Sainte-Chapelle.6)Messiaen desired the first performance of Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum to be in the mountains of la Grave, but a more realistic solution was the Sainte-Chapelle: ‘the sun shining through the windows at eleven in the morning, with gold and blue, and red and violet reflections shining on the instruments and the audience’. Quoted from Entretiens avec Claude Samuel (1988) in Christopher Dingle, The Life of Messiaen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 167–8. Stained-glass windows are also mentioned in vol. 7 of his Traité, where colour translations of chords and modes are described.7)Traité, vol. 7, especially pp. 97–9. According to Yvonne Loriod, this text was written as early as 1970–75. Whether one acknowledges these or not, it is evident that these colour translations, and the faculty of synaesthesia, provide important clues to Messiaen’s compositional practices and are inherent aspects of his musical language. His particular approach to analysis, which was primarily descriptive, had a decisive influence on my own approach to music, although I soon wanted to go beyond the purely descriptive stage in order to reveal the driving forces of the music – the ‘why’ rather than the ‘what’. The ‘why’, in Messiaen’s case was, for a great part, the colours.

Although scarcely mentioned nowadays, the phenomenon of synaesthesia – a combined, simultaneous function of several senses – is well documented. At least since the eighteenth century,8)Louis Bertrand Castel constructed a colour organ (‘clavecin oculaire’) in 1725, so that ‘a deaf person could enjoy the beauty of music with his eyes’. See Jörg Jewanski, Sean A. Day and Jamie Ward, ‘A Colorful Albino: The First Documented Case of Synaesthesia, by Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs in 1812’, in Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 18/3 (2009), pp. 293–303. the subject of ‘colour hearing’ has been discussed among musicians, as the perception of colours matching with other senses is not uncommon. In the twentieth century, Skryabin and Messiaen, among others, both had this somewhat ‘mysterious’ ability.9)See Traité, vol. 7, pp. 97–9, for Messiaen’s own description of the condition.

In fact, Messiaen explicitly calls several of his works a direct result of his coloured visions. He writes concerning Couleurs de la Cité Céleste:

The shape or this work depends entirely on colours. The melodic or rhythmic themes, the complexes of sounds and timbres, evolve like colours. In their perpetually renewed variations, one can find (by analogy) warm and cold colours, complementary colours influencing their neighbours, colours bleached towards white, darkened by black. One can moreover compare these transformations to characters acting on several superposed stages and telling several stories simultaneously.10)‘La forme de cette œuvre dépend entièrement des couleurs. Les thèmes mélodiques ou rythmiques, les complexes de sons et de timbres, évoluent à la façon des couleurs. Dans leurs variations perpétuellement renouvelées, on peut trouver (par analogie) des couleurs chaudes et froides, des couleurs complémentaires influençant leurs voisines, des couleurs dégradées vers le blanc, rabattues par le noir. On peut encore comparer ces transformations à des personnages agissant sur plusieurs scènes superposées et déroulant simultanément plusieurs histoires différentes’. Première Note de l’Auteur in the score of Couleurs de la Cité Céleste (Paris: Alphonse Leduc, 1966).

This statement is significant since it closely relates the colours to the dramaturgy and the dynamic shape of the piece, and explains his particular multi-layered counterpoint of colours. The title of the piece refers to colours (literally!) described in the Apocalypse of St John.

As colour indications frequently occur in the scores of Le Traquet Stapazin, Le Merle Bleu and La Rousserolle Effarvatte, among others, it is almost impossible not to note the colours at all.

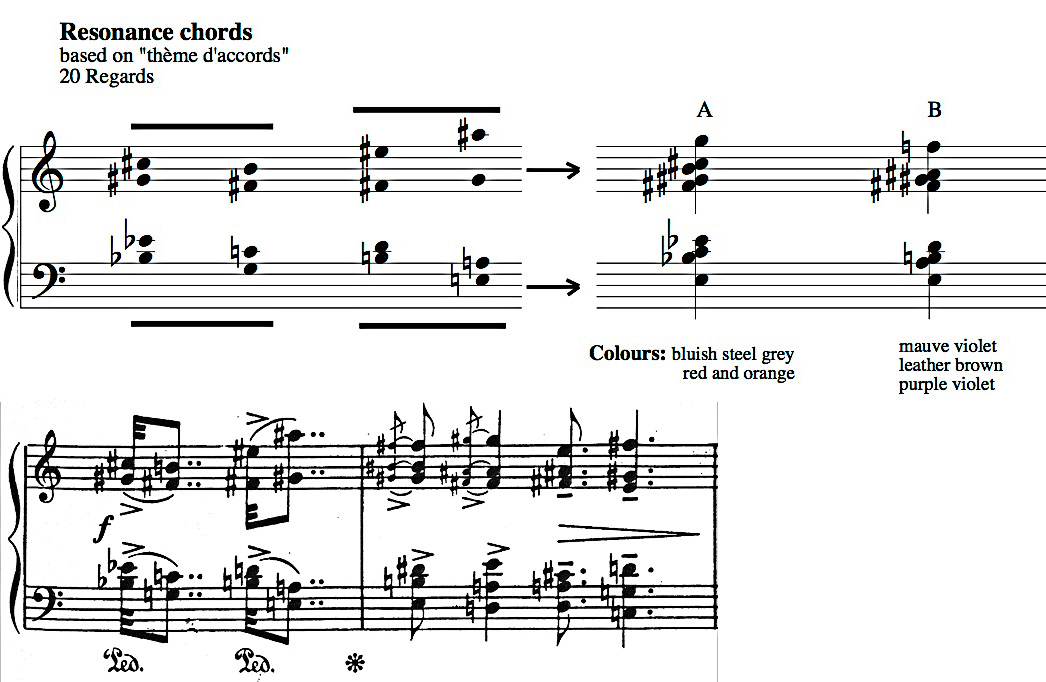

Figure 1 Excerpt of La Rousserolle Effarvatte with the composer’s colour indications in the score. Editions Alphonse Leduc.

In the prefaces to other scores (e.g. Trois Petites Liturgies and Quatour pour le Fin de Temps), Messiaen gives detailed information about the colours connected to modes and chords. However, when I first encountered his works back in the 1960s, the significance of ‘colour hearing’ in relation to his works was generally unknown. I had always been fascinated by the richness of timbre – sound colour – in his music, but had studied it for a number of years without contemplating on the significance of the colours.

With time, my own knowledge of the colours developed, along with a deepened understanding of Messiaen’s musical language. Moreover, the direct contact with the composer over a number of years certainly strengthened my understanding. When the composer and I were interviewed together, in 1988, I took the opportunity to ask him directly – and got a telling answer:

You raise a question there that I hardly speak about since no one believes me. When I hear music, I see corresponding colours. I think everyone possesses this sixth sense, but only a few discover it. I discovered this disease 20 years old at a painter friend’s place. I tried to put these colours into what I wrote. I don’t ask the performers to see the same colours as I do myself – by the way, this is not possible – but to see colours, each in his own way.11)‘Vous soulevez là une question dont je ne parle guère car personne ne me croit. Lorsque j’entends de la musique, je vois des couleurs correspondantes. Je pense que tout le monde possède ce sixième sens, mais que rares sont ceux qui s’en aperçoivent. J’ai découvert cette maladie à l’âge de 20 ans chez un ami peintre. J’ai essayé de mettre ces couleurs dans ce que j’écrivais. Je ne demande pas aux interprètes de voir les mêmes couleurs que moi – ce n’est d’ailleurs pas possible – mais de voir des couleurs, chacun à sa manière’. Interview by Pierre Tournelle, ‘Olivier Messiaen – Le Prêche aux Oiseaux’, in Diapason-Harmonie, 344 (Dec., 1988), pp. 74–77, here p. 76.

The ‘painter-friend’ was, by evidence, Charles Blanc-Gatti. Already when they first met, Messiaen had composed ‘colour music’ having made use of his so-called ‘modes with limited transpositions’ that he later defined as products of his colour hearing. But the quotation above reveals several things. It is remarkable that Messiaen, even at the age of 80, was still embarrassed about his ‘sixth sense’, since he describes it as an illness. At the same time, he states that everyone possesses it. This has indeed been confirmed by neurologists: synaesthesia is now defined as an inborn connection in the brain that most people lose as they grow up, but of which many of us keep a small part intact.12)See for instance Daphne Maurer, Laura C. Gibson and Ferrinne Spector, ‘Synesthesia in infants and very young children’, in The Oxford Handbook of Synesthesia, ed. Julia Simner and Edward M. Hubbard (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 58: ‘The recent research findings reviewed in this chapterlends cogent support to the hypothesis that all individuals experience something like synesthesia as infants, with remnants of these cross-modal associations still observable in adulthood, either explicitly in synesthetes or implicitly in all other people’. In Messiaen’s time, however, synaesthesia was often met with considerable scepticism. As late as in 2002, when the seventh volume of Messiaen’s Traité was finally published, Alain Louvier still addressed this point with some scepticism:13)Richard E. Cytowic notes a ‘vogue’ of interest (measured in the form of published articles) between 1880 and 1930, which then declined. Between 1930 and 1990, fewer than 10 articles per decade were published on this subject (only one paper in the 1960s). The 2000s, however, saw almost 60 published papers on synaesthesia. See ‘Synesthesia in the twentieth century: Synesthesia’s renaissance’ in The Oxford Handbook of Synesthesia.

How easy it is to poke fun in front of the lavishly decorated colours that dwell in this familiar mode 2 simply transposed! Strange conception of the affinity between sound and colour, superbly arbitrary for the “non-seers” that we are … Only the immense respect that the students had for Messiaen withheld them from teasing him too much on this question, [which was] clearly more subjective than scientific or experimental.14)‘Comme il est facile de se moquer devant le luxe de couleurs chamarrées qui habillent ce familier mode 2 simplement transposé! Conception étrange du rapport son-couleur, superbement arbitraire pour les “non-voyants” que nous sommes … Seul l’immense respect que ses élèves avaient pour Messiaen les retenait de trop le taquiner sur cette question, à l’évidence plus subjective que scientifique ou expérimentale’. Traité , vol. 7, p. IX (from the preface).

Of course, the connections between colour and sound are subjective, as Messiaen himself explains (quoted above). This should not prevent us, however, to consider his colour hearing as a vital part of his musical language. The subject was for long a delicate one, and has hitherto been only superficially researched – partly because the volume of Traité containing the colour descriptions was the last one to be published.15) Paul Griffiths is one scholar who did acknowledge early on the importance of Messiaen’s synaesthesia. In his article ‘Catalogue de couleurs’, The Musical Times, 119 (1978), pp. 1035–37, for the composer’s seventieth birthday, as well as in his book Modern Music and After (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), he discusses the use of coloured chords in some of Messiaen’s works, but without possessing the knowledge of Messiaen’s own descriptions which were to be published much later. Robert Sherlaw Johnson refers to Samuel’s Entretiens avec Olivier Messiaen (1967, ch. 2) and the few colour associations mentioned in Technique and their importance in ‘articulating the musical form’. See Johnson, Messiaen (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975), pp. 119–20. Johnson correctly concludes: ‘As a consequence of these associations, one can speak of “colour” chords, and a melody which has harmonies associated with it could be said to be “coloured” by these harmonies, rather than “harmonized” in the classical sense’ (p. 19). Jonathan Bernard asks ‘how one might follow Messiaen in his colour hearing … towards a deeper understanding of his music’ in The Messiaen Companion, ed. Peter Hill (Winona, MN: Amadeus Press, 1994), p. 204, and asks many of the questions which were answered in Traité, vol. 7. On the other hand, Paul E. Dvorak of University of North Texas published a study on the relation between pitches and colours in Messiaen’s Couleurs de la Cité Céleste, based on spectrum analysis. In my opinion, this pulls the understanding of Messiaen’s synesthesia in a wrong direction, suggesting that a relationship between the pitches of a chord and the resulting colours can be scientifically proved. See http://www.pauldworak.net/publications/music/RCE/icmpc11_full_paper_dworak.pdf accessed May 2014.

Certain people had of course known the implications of Messiaen’s colour hearing for years, notably his widow Yvonne Loriod, who generously shared her insights with me. Loriod put at my disposition descriptions of the various modes and chords, which were later to be published in the last volume of the Traité. As this publication was delayed, one had to wait a long time for the full secrets of the colours of modes and chords to be revealed to the public.16)Another limitation for the work’s distribution is the fact that the complete Traité is not yet available in any other language than French.

But even after it appeared, and despite the growing research interest in Messiaen’s music, scholars often avoid this subject on grounds of its subjectivity. Gareth Healey, for instance, argues that it is ‘impossible to draw any meaningful conclusions’ (!) from an approach which ‘precludes independent exploration’.17)Gareth Healey, ‘Introduction’, in Messiaen’s Musical Techniques: The Composer’s View and Beyond (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), p. 2, footnote 1: ‘Messiaen’s association of colours with certain of his harmonic technique is an element of his language that precludes independent exploration. Due to the highly personal nature of this synaesthetic connection and despite the obvious importance given to colours in Messiaen’s writings, it would be impossible to draw any meaningful conclusions from an investigation into this link’. Similarly, Christopher Dingle finds it satisfactory to ‘touch upon aspects of Messiaens colours associations as a useful metaphor, but, due to the highly personal nature of this phenomenon … believ[es] it necessary only to be aware of what for the rest of us tends to be, ironically, a grey area’.18)Christopher Dingle: Messiaen’s final works (Ashgate, 2013), p. 9.

With my project I wanted to challenge this view. Given the importance that Messiaen himself assigned to his colour associations, they should be explored beyond the stage of merely ‘being aware of’ them. This exploration should take the music itself and the composer’s own comments as its starting point (its interest lies therein, not in ‘independent exploration’). More than 20 years after his death, the options for exploring and analyzing his works according to methods and preferences described on the thousands of pages of Traité and his other writings, are far from exploited. Having known of his fascination for colours, and familiar with their application long before they became published in their entirety (2002), relating Messiaen’s music to his colour hearing has long been an inherent part of my approach to these works. In my project, I have attempted to work out colour realizations – one might label them colour analyses – of Messiaen’s works based on his own colour descriptions. Rather than doing written exploration, the best way to make these connections clear is, in my opinion, to visualize them.

Earlier projects

In the early nineties, I had the opportunity to work out a solution for the colour keyboard in Aleksander Skryabin’s Promethée, Poème du Feu, op. 60, where the score calls for a tastiera per luce noted in a two-voiced orchestra part, notated above the piccolo. This colour part had been shown before, but in our opinion not in an adequate way. In the LUCE project group, we set about to realize Skryabin’s visions on a set of five foreground screens and a background, illuminated by 360 lamps controlled by a computer system, using historic sources to obtain a visual result close to the original intentions.19)More details about this project can be found on http://www.austbo.info/lucepage/LUCE1.html The LUCE project also came to include a realization of the colour part in the first movement of Skryabin/Nemtin’s Acte Préalable.

This work with the LUCE project in the Netherlands gave me an experience of coloured projection that sparked the idea of using a similar procedure for certain works of Messiaen. On one occasion, having performed the Catalogue d’Oiseaux in The Hague, I had a discussion with the composer, who was present at the concert, and I was proposing to show images of the landscapes he indicates in the scores of these pieces. He thought this was ‘une très bonne idée’. Some years later, in 2001, I performed the Catalogue in Oslo with a series of colour slides taken of these landscapes, treated to emphasize the colours present in the score. On a later occasion, at the Bergen Festival, I included some moving pictures in projections accompanying Le Merle bleu. These projections were based on descriptions of the colours found in the scores themselves, combined with my accumulated knowledge of his colour schemes.

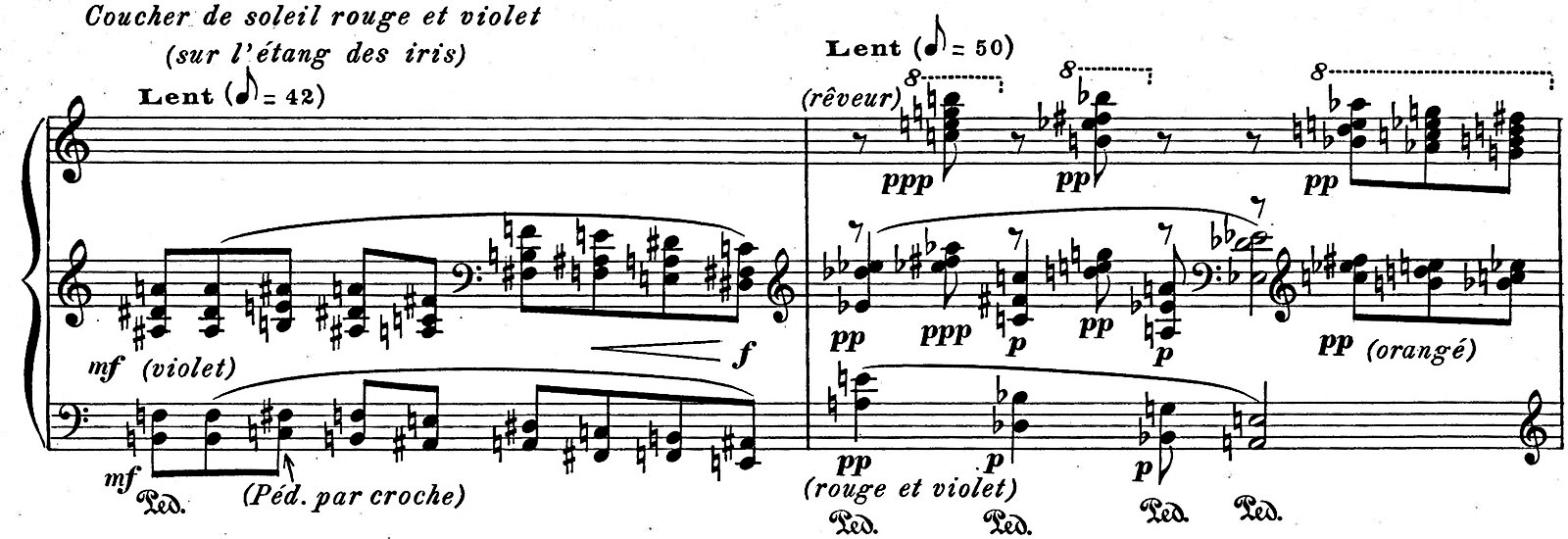

After having attempted to use visualization at certain performances of Messiaen’s works, I became more and more fascinated by the detailed descriptions that I discovered in the various sources. One work especially intrigued me: Trois Petites Liturgies de la Présence Divine, which Messiaen at several occasions called his best work, is entirely based on colours. In the preface to this work, Messiaen writes:

The music of TROIS PETITES LITURGIES is above all a music of colours. The ‘modes’ that I use there are harmonic colours. Their juxtaposition and their superposition give: blues, reds, blues striped with red, mauves and greys spotted with orange, blues spiked with green and circled with gold, purple, hyacinth, violet, and the glittering of precious stones: rubies, sapphire, emerald, amethyst – all that in draperies, in waves, in swirling, in spirals, in interlaced movements. Each movement is assigned to one ‘kind’ of [divine] presence… These inexpressible ideas are not expressed – they remain in the order of a dazzle of colours.20)‘La musique des TROIS PETITES LITURGIES est avant tout une musique de couleurs. Les “modes” que j’y utilise sont des couleurs harmoniques. Leur juxtaposition et leur superposition donnent: des bleus, des rouges, des bleus rayés de rouge, des mauves et des gris tachés d’orangé, des bleus cloutés de vert et cerclés d’or, la pourpre, l’hyacinthe, le violet, et la rutilance des pierres précieuses: rubis, saphir, émeraude, améthyste – tout cela en draperies, en vagues, en tournoiements, en spirales, en mouvements entremêlés. …les trois parties sont dédiées à trois ’genres’ de Présence. …Ces notions inexprimables ne sont pas exprimées – elles restent dans l’ordre d’un éblouissement de couleurs …’ ‘Notice analytique’, in the score of Trois Petites Liturgies (Paris: Durand, 1952). The exact passage is repeated in Traité, vol. 7, p. 194.

When an opportunity presented itself to realize the colour visions in this piece, I seized it. It was the ideal playing ground for trying out his minute descriptions of some of his ‘modes à transpositions limités’ and ‘couleurs harmoniques’, since these were for the first time presented in the preface in the score of this piece.

Correspondence between colours and musical material

Sources: Behind the surface

As already touched upon, Messiaen himself has provided considerable amounts of information that makes colour translations possible, although, it must be said, he probably never intended to have the works performed with actual colour projections. Still, I felt it was legitimate to realize a visualization of his colours, as I had gotten his concession earlier on, in order to judge its effect on the audience. This cannot be assessed without actually doing it.

For the final result to materialize, meticulous source studies were required. Messiaen’s information on the colours and shapes was used to translate every single passage of more than two hours of music into suitable visual material. In other words, this was a huge analytical task, where all the available sources had to be consulted to ensure an adequate translation into colours. The resulting projections may thus be seen as alternative analyses of the works; analyses in colours, shapes and motion.

In order to account for my choices, it is necessary to write in detail. Ideally, the reader should study this text, including videos and figures, along with the scores of the actual musical examples, as they are too extensive to include. As it is not my intention here to give an introduction to Messiaen’s style or composition technique as such, the reader who is familiar with harmony and with the modes, chords and techniques associated with Messiaen’s compositions, will follow me more easily.

What follows is a compilation of all the quotations from the Traité and the scores relevant for visualizing the colours in Messiaen’s mind, along with my comments, as well as pictures and videos from the project. The chapters in the Traité, vol. 7 (especially chapters 3 and 4) devoted to the descriptions include the transpositions of all the modes, at least those he had continued using, after having dismissed the use of the modes 5 and 7 from his original set presented in his Technique de mon langage musical from 1944.21)Traité, vol. 7, p. 107n. Moreover, these chapters contain the descriptions of all the 12 transpositions of the classified chord types that he used systematically. These are:

-

- Chords with inversions transposed on the same bass note (‘Accords à renversements transposés sur la même note de basse’)22)Called ‘Accord sur la dominante’ in Olivier Messiaen, Technique de mon langage musical (Paris: A. Leduc, 1944; translated as The technique of my musical language, by John Satterfield (Paris: A. Leduc, 1956.))

-

- Contracted resonance chords (two types) (‘Accords à résonance contractée’)

-

- Turning chords (‘Accords tournants’)

-

- Chord of the chromatic total (‘Accord du total chromatique’)

Also, he describes a series of chords from Sept Haïkaï, derived from the ‘turning chords’. What he doesn’t include, are chords based on certain intervals, often tritones and minor ninths, which do not fit in any of the modes, or aggregations based on 12-tone rows. There is a multitude of such unclassified chords in his music, which are difficult to analyse with respect to colour. I will address the specific challenges rising from this fact below.

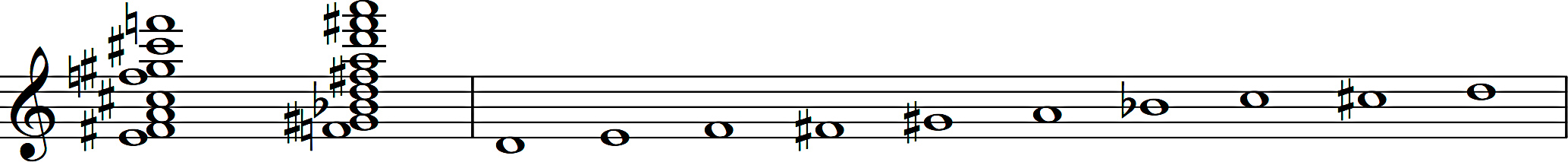

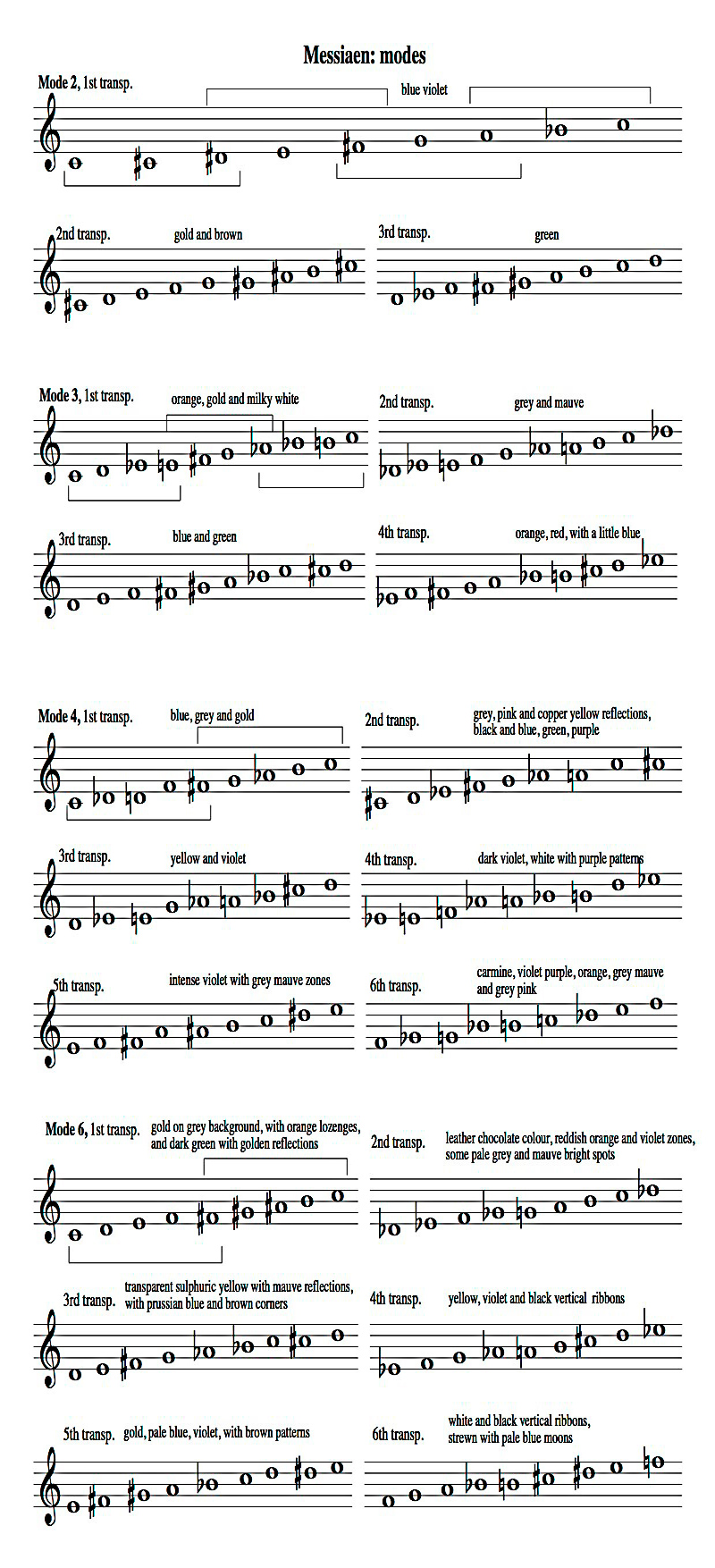

Modes

Messiaen developed his own set of modes around the age of 20. Given their symmetrical construction, they can only be transposed a certain number of times, and this gives an effect that Messiaen calls ‘le charme des impossibilités’ (the enchantment of impossibilities). This magic effect is one that provokes coloured visions, where each transposition of each mode corresponds, as it were, to a different coloured landscape. As he explains, ‘these modes are neither melodic nor harmonic, they are colours’.23)‘Ces modes ne sont ni mélodiques, ni harmoniques, ce sont des couleurs’. Traité, vol. 7, p. 107.

It is important to understand that it is not the single notes of a mode that produce colour, but the chords, or rows of chords within the same mode. When several consecutive chords within the mode are heard, the colour combination will emerge in its totality. In Figure 1, for example, such a series of chords in mode 45 is seen in the first bar, giving the violet colour.

The descriptions of the modal colours changed very little during Messiaen’s life, in spite of slight deviations, for instance in his first works, such as the Huit Préludes. This remarkable consistence leads to the conclusion that the texture or the scoring of a certain passage doesn’t significantly influence its colours, only in terms of saturation or luminosity, as described in his Conférence de Notre-Dame in 1977,

…the combination of colours stays the same with a simple octave transposition, with a brightening if it is a higher octave, and a darkening if it is a lower one.24)‘la combinaison de couleur reste la même au simplement changement d’octave, avec un éclaircissement s’il s’agit d’une octave aiguë, avec un assombrissement s’il s’agit d’une octave grave’. Olivier Messiaen, Conférence de Notre Dame (Paris: Alphonse Leduc, 1978).

or in certain of his detailed colour descriptions in the Traité:

15th chord: it belongs to mode 33 – it is in A major blue – the presence of the G sharp adds a little gold, the doubling at the higher octave of the C sharp and the F natural add pale green. 16th chord: it is again in mode 33 – it is light green and light silvery blue, the B flat and the G sharp add a little orange.25)‘15e accord: il appartient au mode 33 – il est en la majeur bleu – la présence du sol dièse ajoute un peu d’or, la doublure à l’octave aiguë du do dièse et du fa bécarre ajoute du vert pâle. 16e accord: il est encore en mode 33 – il est vert clair et bleu clair argenté, le si bémol et le sol dièse ajoutent un peu d’orangé’. Traité, vol. 5/1, p. 354.

The last quotation shows that in the case of the multi-coloured modes, a certain colour can take dominance over the others, depending on which tonal dominance is heard in a certain chord, or which notes of the chords are particularly emphasized.26)See also Technique, ch. XVI, p. 58: ‘All the modes of limited transpositions can be used melodically, and especially harmonically, melody and harmony never leaving the notes of the mode. … They are at once in the atmosphere of several tonalities, without polytonality, the composer being free to give predominance to one of the tonalities of to leave the tonal impression unsettled.’

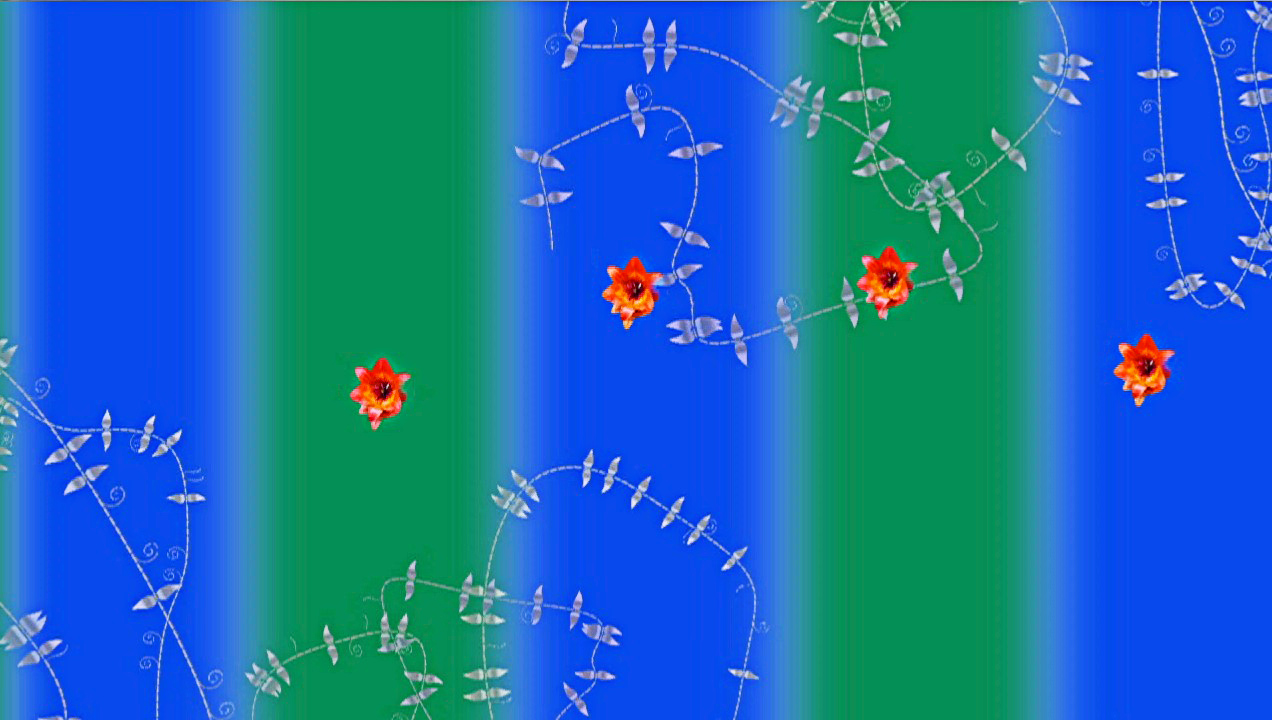

Figure 3 Colour visual of mode 33.

The two chords discussed are shown in Figure 2, along with mode 3 in its third transposition. This transposition is described as follows:

Broad vertical banners, alternatively cobalt blue and bluish green, rather dark. On this background, rare and sparse, some saffron lilies and some silver lianas. Main colours: blue and green.27)This and subsequent colour descriptions are taken from Traité, vol. 7 (chapter III), unless otherwise noted. Translations by the author.

A picture corresponding to this description is shown in Figure 3, and one will notice that the colours of the chords in question are more or less present in this picture, where the gold and the orange are seen in the saffron lilies. Changing from one of these chords to the other will change the balance between the various colour components in the picture.

Similar things are described in connection with other modes, and occasionally the colour of a certain chord belonging to a mode can deviate quite a lot from the basic colour of the mode. It should be added here that many of the modes, especially the transpositions of modes 2 and 3, could be seen as combinations of different tonalities, which might explain their multi-coloured character. Figure 4 shows a survey of the modes with their corresponding general colours.

Figure 5 The stained-glass windows of Sainte-Chapelle, Paris.[/caption]

Figure 5 The stained-glass windows of Sainte-Chapelle, Paris.[/caption]

The mode 21, for instance, can be seen as a combination of four tonalities: C major, E flat major, F sharp major and A major. Hence, the mode contains a combination of different colours that will produce a vibrating effect when seen simultaneously, much as in a stained-glass window of a cathedral such as Chartres, or in the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, that meant so much to Messiaen. He kept returning to stained glass, and to him, it became a metaphor transcending this life:

Stained glass is one of the most wonderful creations of man. You are overwhelmed. And I think this is beginning of Paradise, because in Paradise we are overwhelmed.28)Everyman, BBC Television 1988, quoted from Hill, Subtitle in the score., p. 4.

The vibrating, ‘overwhelming’ effect of four simultaneous tonalities also applies to the second and third transposition of this mode. Since each one ‘contains’ four major triads, all 12 major tonalities are related to one or another of these transpositions. The minor triads, by the way, relate to the same transpositions, since both the minor and major third are present in the mode.

Bartók used this symmetry to place all the 12 tones/tonalities in a system of axes, where each note in a piece with a defined tonal centre relates either to the tonic, the dominant or the subdominant axis.29)For a discussion of this topic, see Ernö Lendvai, Béla Bartók, An analysis of his music. Kahn & Averill, 1971), p. 3. Messiaen does precisely the same when he substitutes the three tonal functions with the three transpositions in pieces like ‘Regard du Père’ from Vingt Regards.

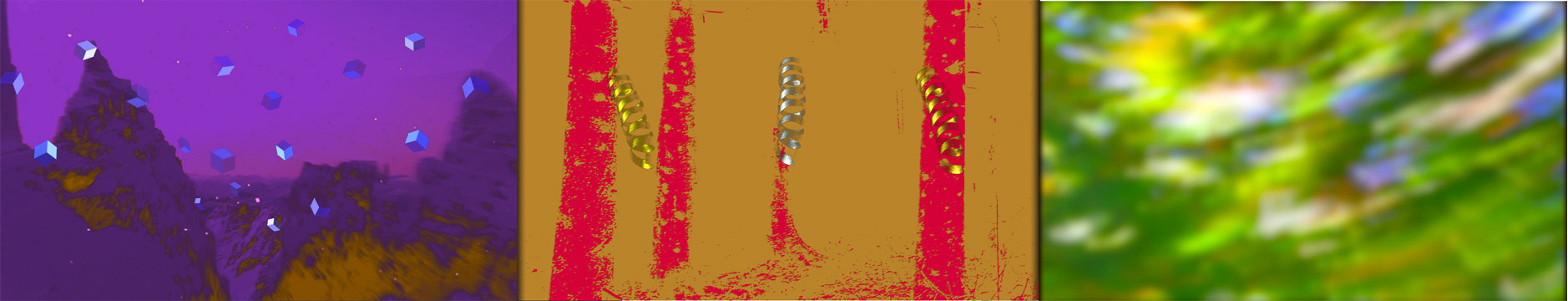

The description of the three transpositions of mode 2 follows here, along with our rendering of these descriptions.

Mode 2, 1st transposition.

Blue violet rocks, scattered with small cubes of grey, cobalt blue, dark Prussian blue, with some reflections of violet purple, gold, ruby red, and stars in mauve, black and white.

Main colour: Blue violet

2nd transposition.

Spirals of gold and silver on a background of vertical banners in brown and ruby red.

Main colours: Gold and brown

3rd transposition.

Leaves in light green and prairie green, with spots of blue, silver and red orange.

Main colour: green

We shall discuss the choice of graphic material for these images below. It should be noted that they are meant as moving pictures, not stills. See also Video 6.

Non-modal chords

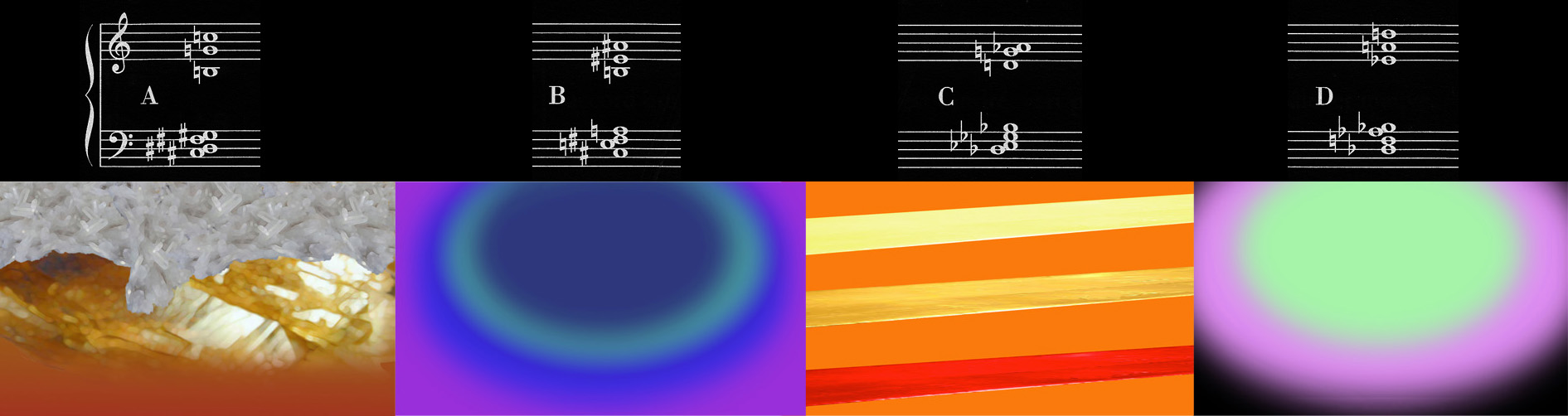

Although Messiaen used a great number of chord types, there are certain species that became archetypical of his language, the most characteristic being the contracted resonance chords, and the chords with inversions transposed on the same bass note. We won’t enter a discussion here on the genesis of these chords, as they are amply explained by Messiaen himself in the Traité.30)Messiaen, Traité, vol. 7, pp. 135–64.Common to these chord types are the consonant (tonal) components along with dissonant ones; the chords are defined as classified tonal chords with added notes. The tonal core determines the main colour, while the dissonant added notes produce complimentary colours or reflections. The chords with inversions transposed on the same bass note are derived from a dominant 13th chord with tonic instead of leading note and added dissonant notes in the form of a double appoggiatura, inverted three times, but transposed down to maintain the same bass note for the four inversions (A, B, C, D of Figure 7). The tonal content of the chord changes when the chord is transposed, thus calling for different colours. In most cases, the colour descriptions are made from top to bottom, unless otherwise noted. As an example, Figure 7 shows the chords with inversions transposed on C sharp, based on the dominant of F sharp, along with our colour renderings:

The colours of the four chords are described as follows:

A. Superior zone: Rock crystal and citrine.

Inferior zone: Copper colour with golden reflections.

B. Large sapphire blue sheet, circled by less intense blues (fluorine blue, light Chartres

blue) and recircled by violet.

C. Orange, with ribbons pale yellow, red and gold.

D. Pale green, amethyst violet, and black.

Major and minor triads

In the case of the chords B, C and D we see a clear tonal dominance. The chord B is dominated by A Major, the chord C by G flat major and the chord D by D flat major. The colour descriptions give us some clue as to which colours belong to which tonalities. A major is clearly dominated by blue, and G flat major by golden orange. The triads with added sixth that we see in the left hand of these chords are very colourful representations of the respective tonalities, where the added sixth enhances the saturation. These chords, in Messiaen, must in no way be seen as inversions of the relative minor 7th chords, as the sixte ajoutée has been a tradition in French music since Rameau.31)As Messiaen notes: ‘The most used of these [added] notes is the added sixth. Rameau foresaw it’. See Technique (Eng. Trans., 1956), p. 47.

The two tonalities discussed here are also components of the first transposition of mode 2. The colours of that mode confirm the connection of blue-violet with A major and gold with G flat/F sharp major.

Triads, with or without the added sixth, tend to be more monochrome than the more complex chords or multi-coloured modes.

Deducting from a number of sources in Messiaen’s descriptions, I have established a tentative list of major and minor chord and their respective colours:32)Enharmonics make no difference to the colour schemes.

| Major | Minor | |

| C | White | Yellowish grey |

| C# Db | Grey green* | Black-gold* |

| D | Green | Green |

| Eb | Rose-violet* | Dark red |

| E | Red | Orange* |

| F | Pale green | Bluish green |

| F# Gb | Gold | Acid green |

| G | Yellow | Red orange |

| Ab | Sapphire blue | Violet |

| A | Blue | Pale blue |

| Bb | Red grey | Dark orange* |

| B | Brown | Grey w red* |

The colours marked with an asterisk are ambiguous, since the descriptions are not consistent.

Shapes and movements

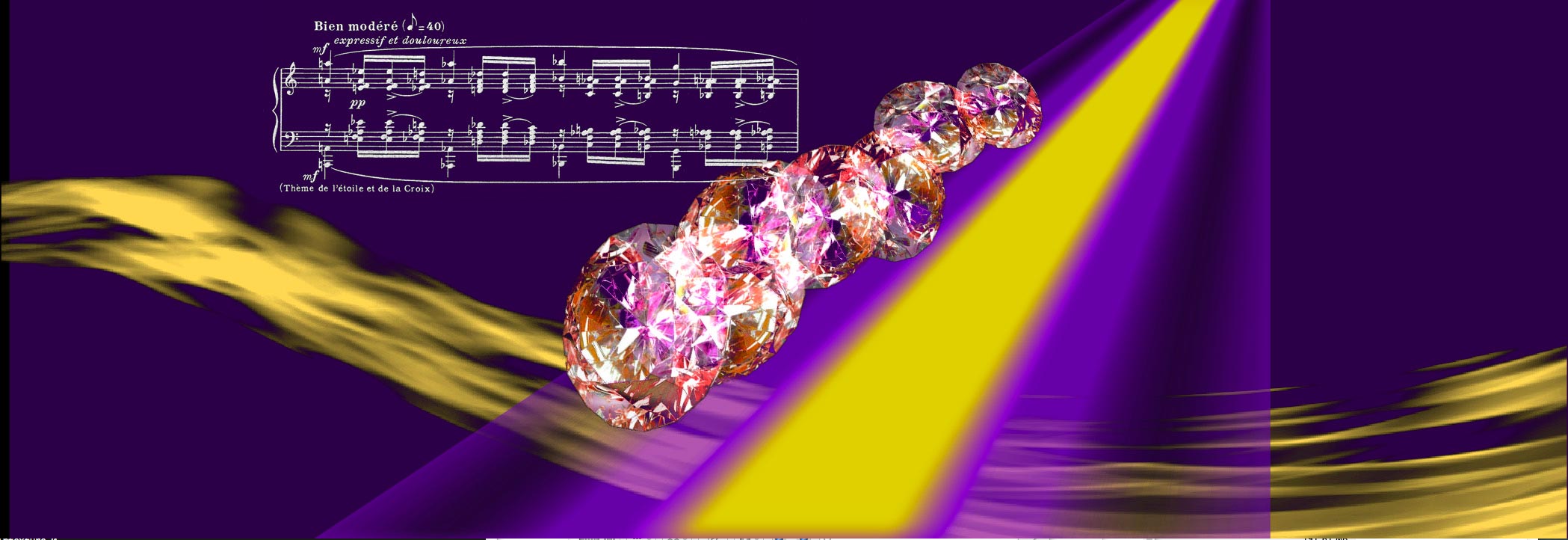

From the previous examples it will be clear that the colours do not exist merely as colours; they have very specific shapes as well, which ought to be respected in a visualisation. In fact, any colour needs a shape to be observed. There is another aspect to these shapes: they are not static, but constantly glowing, glittering or moving in various ways. Messiaen describes certain kaleidoscopic qualities in his harmonies, like here, referring to the chords with inversions transposed:

we obtain a fluorescence, an opalescence, with four changes of colour. This radiation, these iridescent reflections, evoke certain butterflies with wings – blue of all blues – that become green or violet according to the ambient light. Even better, they imitate the coloured movements of gemstones and jewels.33)Messiaen, Traité, vol. 7, p. 138: ‘… nous obtenons une fluorescence, une opalescence, à quatre changements de couleur. Ce rayonnement, ces reflets irisés, évoquent certains papillons dont les ailes – bleues de tous les bleus – deviennent vertes et violettes suivant les incidences de la lumière. Mieux encore, ils imitent les mouvements colorés de gemmes et des pierres précieuses’.

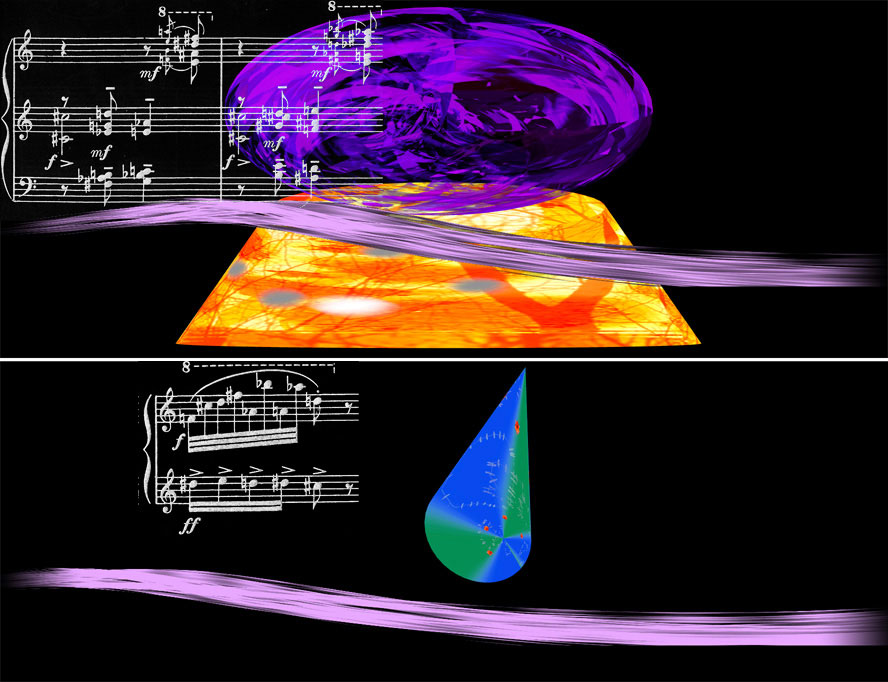

As an example of visualisation of jewels, Video 2 renders the following chords with inversions transposed:34)Transposition 8 A (on A flat):The numbers of the transpositions refer to Messiaen’s numbering in the Traité, vol. 7, chapter III.

Facets of crystal: yellow, mauve, pale blue, pale green. Rose, amber degraded towards white – with some gold around.

8 B: Designs in white and golden spirals, on carmine red and leather brown background.

Transposition 4 A (on E): Vertical ribbons: green, violet, dark blue.

4 B: White, gold.

Transposition 3 A (on E flat): Mauve campanulas on white and light grey veils.

3 B: Crystals: burnt earth, amethyst violet, light Prussian blue, warm red chestnut – with golden stars

Transposition 11 A (on B): Leather brown, with blue matte lapis lazuli and a little violet above

11 B: Lemon yellow with red spots

Although not all of these descriptions include crystals, they are here integrated into a continuous picture to render this particular series of chords.

Video 2 Visualisation of jewels: chords with inversions transposed.

Motion must be introduced in correspondence with the musical content. It is sometimes ensured by rapid changes of colours, such as in the chord progression in ‘Par Lui tout a été fait’ shown in Figure 8. The colours of these chords have been deducted from a variety of sources. Only the last two, a concentration of the ‘chord theme’ proper to Vingt Regards, are specifically described:

Steel blue grey crisscrossed with red and orange, mauve violet spotted with leather brown, circled with purple.35)Messiaen, Traité, vol. 2, p. 438: ‘un gris bleu d’acier traversé de rouge et d’orangé vif, un violet mauve taché de brun cuir et cerclé de pourpre violacée.’

Video 3 Colour visuals of the chord progression (Grappe d’accords) shown in Figure 8. The speed of the changing colours provides a kaleidoscopic effect that corresponds to the musical effect of the passage.

The project materializing

The preparation of the colour parts for Trois Petites Liturgies and Vingt Regards involved

- analysing and identifying every mode and chord, and connecting these to Messiaen’s envisioned colours and shapes (found in his Traité and other texts)

- collecting suitable graphics and videos

- combining the visuals into moving pictures for projection on a big screen

Furthermore, it involved finding technically and artistically satisfactory ways to control and coordinate the colour projections in the live performance:

- choose or develop graphic and video software to design, incorporate and control moving pictures

- construct and program a keyboard to control the colour projections

- write out a part for the pianist playing the electronic keyboard, controlling the projections

- make and rig screens on the stage for the projections, for the audience to get a good view of both these and the performers

In the process, I found an indispensible ally in the visual artist Ricardo del Pozo, who had gathered great experience in live colour projections combined with music. Together, we worked out the solutions for the colours of Trois Petites Liturgies (described below) to be projected on the existing screen in the concert hall at NAM.

Based on the concept of this preliminary stage, but enhancing this with some new features, we then worked out the parts for 16 of the 20 pieces of Vingt Regards. (Four of them were considered inapt or too complex to justify a translation into colours). Here, we used a screen of 2×7 metres, suspended behind the piano, in order to enclose, as it were, the music in the colours.

Basic choices

Our first task was to render as faithfully as possible the shapes that Messiaen describes. Many of the descriptions, such as the one of mode 21, include images from nature. To render the rocks, we used pictures from Norwegian landscapes. We could also have used the Alpine landscapes of the region where Messiaen spent his summer holidays, and in particular the region of la Grave and of the peak la Meije, where I have taken many photos. But when we came across a video by MagicAir called ‘Norwegian sunrise’, we realized that this was exactly what we needed in order to render this mode. Therefore, we bought the rights for this video to use in the project. It contains some quite spectacular air views of the rocks of the Sunnmøre region in western Norway.

By a tilting movement of the camera flying over a group of these rocks, combined with swirling movements of the cubes belonging to mode 21, an ecstatic progression is rendered at the end of the second movement of Trois Petites Liturgies, ending in an A major triad, represented by another mountain picture assigned to this particular cyclic motive (see Figure 10). Video 4 shows this excerpt from the performance.

Video 4 Sequence of Trois Petites Liturgies, II.

The particular image of mode 21 calls for a somewhat surrealistic fusion of natural and geometric shapes; rocks and cubes. Other descriptions of Messiaen are mainly geometrical, such as the vertical banners of mode 22. Here, we chose to base our image on tree trunks from a pine forest, manipulating the colours and superposing images of golden spirals. Panning or tilting, as well as moving the spirals, provided the necessary motion. Our reason for this choice of motive is that we considered it more harmonious to use pictures from nature for all the three transpositions – the third transposition is rendered simply by a blurred shot of leaves in a tree – than to switch between abstract, computer-animated graphics and natural images. However, a careful balance between these elements had to be found at any given place in the scores.

There are numerous other references to nature in the descriptions, especially to flowers. Where no shapes were defined by Messiaen (though most have at least some hint of spatial distribution, such as from high to low etc.) we had to determine the shapes ourselves. It is worth repeating that a colour with no shape cannot be seen. The shape can be anything from vague, fog-like ones to sharply defined forms, crystalline particles or reflections in water. When elaborating the colour play, we had to make these choices constantly, and they depended on the character, density and luminosity of the music at any given point. The movements that we wanted to generate in the colour play also had to correspond to the musical movements of a given passage, without becoming too illustrative.

Technical choices

My work on the visualisation of the modes and chords had gone on for several years, using common graphic and video software. However, in order to accommodate the graphics in a colour part to be shown along with the music, an environment was required that could provide the following:

- Control of video and graphic material in terms of scaling, positioning and rotating.

- Use of several layers of such material with controllable transparency.

- The manipulation of the colours of these layers: RGB, contrast, brightness etc.

- A system of script-driven processes to provide a random access archive of pictures.

- A MIDI-driven interface to trigger the various pictures and to control variables.

The MAX/Jitter application was found the most suitable for fulfilling these requirements, along with the Jamoma scripting environment and modules developed specifically for this project. Ricardo del Pozo was responsible for the setup, which evolved as we went along. For the performance of Trois Petite Liturgies, performed on 28 February 2013, we made use of four video layers. However, this presented some limitations, and for the performance of Vingt Regards, we were able, thanks to a new video standard,36)Quick Time Hap Codec. to expand the number of layers to 10 plus a background layer. This enabled smooth transitions between the different pictures, and a high complexity of the visual result.

Once this environment had been set up, the video and graphic material had to be collected. As mentioned above, we made use of commercial video material, but also made our own videos and graphic files. All the videos were taken in Norway, most of them in the Oslo area, in different seasons.

The pictures had to be generated in real time and to be triggered from a musical instrument, since the average light technician would not be able to follow the complex score at a console. The control from a MIDI-keyboard had proven to be the best solution for this, as I had experienced in the Skryabin/LUCE project. For this purpose, the range of an 88-key MIDI controller is divided in several sections, often corresponding to octaves, but not necessarily. Each section is assigned certain functions, the lower ones triggering the various scripts, while the others control things like the colours of certain objects, the start/stop and speed of the videos, and a number of other parameters, depending on the active script. The actual keyboard we used is the same one I built for the LUCE project; we soldered circuit boards, connected it to a high-quality keyboard and had a carpenter frame it in a suitable exterior.

Then, a colour part had to be developed for the player. This part bears little resemblance to the score, since the notes are intended solely to synchronize the visual part to the rest of the music, which the player can follow on a cue staff.

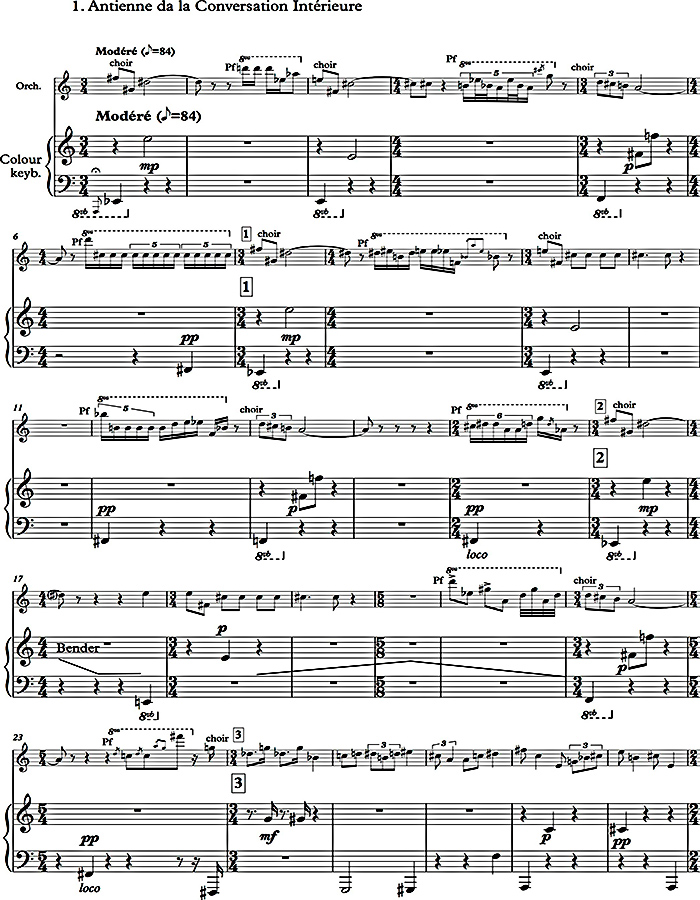

Figure 9b shows a page from the colour part of Trois Petites Liturgies. The part makes sense only in combination with the technical setup of the software and the equipment we used for this performance. Both the aftertouch pressure and the bender wheel were used to control certain parameters. In Vingt Regards, the sustain pedal was used as well, for general blackout.

Trois Petites Liturgies

Choices in Trois Petites Liturgies

A lot of the musical material in this piece can be easily translated to colours by means of Messiaen’s descriptions; but certain elements pose difficulties. Typically, the larger part of the second movement presents challenges, since, although it is clearly in A major, many of the harmonies in the web of musical layers are not classified. Many of these details had to be sacrificed to ensure the impact of the main colour. The refrains are certainly blue (A major), whereas the couplets evolve around the dominant (E major, red) followed by mode 21 (blue violet). In the first couplet this is mixed with interventions in mode 23 (bar 34), accords tournants (bar 47) and mode 31 (bar 51, piano solo before the return of the refrain).

Video 5 shows this passage, from the start of the second movement to the beginning of the second refrain at rehearsal number 2. The landscapes used are chosen from the film mentioned earlier, showing a mountain panorama superposed on glittering reflections to render the figurations borrowing from different transpositions of mode 3, in the refrain, and a multitude of different harmonies, in the couplet.

Video 5 Opening of Trois Petites Liturgies, II.

The couplets and refrains return with increasing complexity. Then, at the fifth refrain,37)Rehearsal No. 8 in the score – unfortunately there are no printed bar numbers. the theme is stated slowly, harmonized completely in mode 2, where the first transposition represents the tonic (A major), the second the dominant, and the third the subdominant. Here, we used the standard pictures of mode 2 in the three transpositions and, although they look very different, they fit together in a certain way since they are all based on images from nature.

Video 6 Excerpt from Trois Petites Liturgies, II (from reh. nr. 8).

The last chords of the refrain are in pure A major and illustrated with the same picture as in the final picture of Video 4, the same chords that end each refrain and act as a kind of cyclic motive since it also closes the first movement:

In this way, a visual counterpart to the thematic structure of the piece is obtained, in the same way as in the first four refrains and couplets. Actually, the fifth and last couplet returns to the same picture as the other couplets, and combines this landscape with geometric shapes coloured according to the various modes and chord types that harmonize this couplet, as can be seen in the second part of Video 6.

In the first movement, a different part of the mountain film is used for the outer parts of its ABA structure. The landscape is treated as purely abstract forms. Later, in the middle section, a combination of abstract and natural forms is again used to render a succession of events found in Appendix 2.

Video 7 Excerpt of Trois Petites Liturgies, I.

As the score gets charged with musical layers, the rendition of all the colours becomes almost impossible. A limit is probably reached in the passage from the third movement shown in Video 8. Here the following elements are superposed:

- Main theme in choir, piano left hand, later celli and basses, written in mode 45 (violet)

- Ascending chords in second violins and violas in mode 33 (blue and green stripes)

- Descending chords in first violins in mode 43 (yellow and violet)

- Passage in piano right hand, 12-tone (silvery, with a little red and orange)

- Chinese cymbal, flash of grey38)Descriptions taken from Traité, vol. 7, p 212–13.

The landscape here is yet another rock formation that reflects the terrifying impact of the passage, described by Messiaen as ‘the effect of vertigo facing the opening abyss’.39)Traité, vol. 7, p. 213: ‘l’effet de vertige devant l’abîme qui s’ouvre’.

After this the refrain of the movement is stated in C sharp major, using the three transpositions of mode 2, this time described as follows:

Mode 23 for the dominant: green with gold

Mode 22 for the tonic: gold and brown with silver and ruby red

Mode 21 for the subdominant: blue with gold

The fact that all transpositions now contain gold, comes from the final chord, F sharp major, that colours the whole passage.

Video 8 Excerpt of Trois Petites Liturgies, III.

It would be tempting, in a work with a text, to illustrate the words with images. We have tried to avoid this. Sometimes, the text refers to colours, as in bar 45 of the first movement: ‘Mélodie rouge et mauve en louange du Père (Red and mauve melody to praise the Father)’, when the music contains quite different colours, here blue, green and gold. The correspondence with the character of the music, however, was considered important, although these would have to be rather intuitive choices since there is no reference to landscapes except, at two points, to mountains. The use of mountain landscapes was indeed found relevant since these were Messiaen’s preferred landscapes.

Another illustration that was avoided was that of the birdcalls, as in bar 31 of the first movement, where the piano stays alone with the call of the skylark. The unaccompanied bird calls are not rendered in colours, as can be seen in Video 7 (at 2’05). It would be childish and inappropriate to show the birds at this point.

Vingt regards

Choices in Vingt Regards

Drawing from the experience of the pilot project, we started the work on the final project, the colour part for the piano cycle Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus. In the preface to this work, colours are mentioned only briefly:

More than in all my previous works, I here looked for a language of mystical love, at the same time varied, strong and tender, sometimes brutal, in multicoloured configurations.40) Preface to the score, Editions Durand: ‘Plus que dans toutes mes précédantes oeuvres, j’ai cherché ici un langage d’amour mystique, à la fois varié, puissant, et tendre, parfois brutal, aux ordonnances multicolores.’

However, the composition of Vingt Regards started on 23 March 1944, just one week after the completion of the Liturgies. Therefore, one could assume that the colour descriptions found in the preface of the Liturgies are valid for the next work as well. In fact, they are identical to those in the Traité.

This huge task had to be planned carefully. First, the main themes of the cycle had to be visualized to fit the different pieces where they occurred. A priority list had to be made, and it was soon decided to refrain from colour projections in the pieces 8, 12 and 16. No. 18 remained a borderline case until we saw that it would take too much time to do it well, due to the complexity of the colours here, and we therefore dropped that piece as well. The other pieces were opted out because their colour content was insufficient. In no. 8, ‘Regard des hauteurs’, however, one chord was visualized twice, while the rest of the piece was left black, since it mainly consists of birdcalls.

An intermediate case is no. 6, ‘Par Lui tout a été fait’. This huge piece consists of two main parts, of which the second is explicitly coloured. Here we proceeded to visualize the whole piece, since the description in Messiaen’s preface contains very visual references: to galaxies, spirals and lightning. The first part, a fugue, is mostly in mode 4, with chord material taken mainly from the progression shown in Figure 8/Video 3. All this provides material for the visualisation.

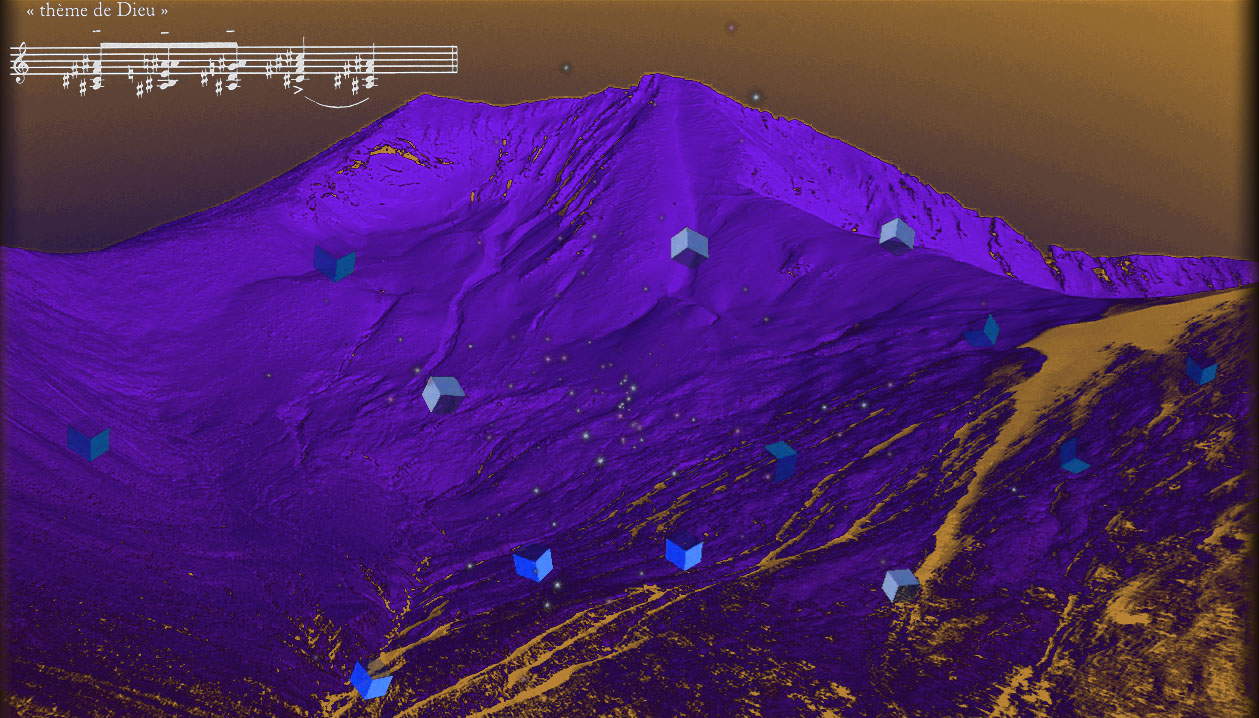

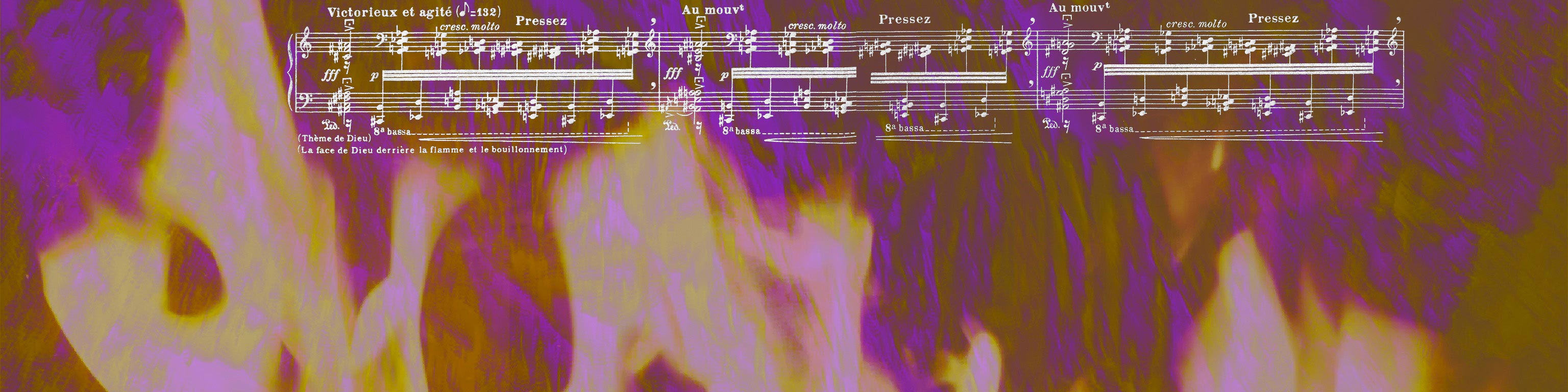

Visual leitmotives: Thème de Dieu

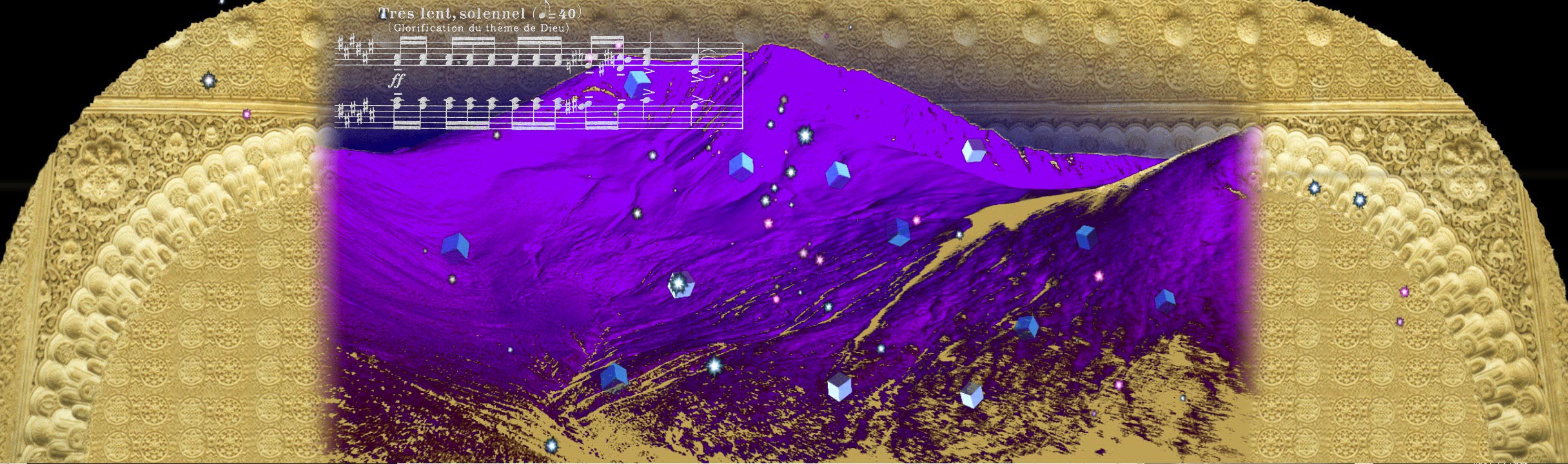

The most important theme of the cycle is the Thème de Dieu (God’s theme). It is exposed in the first piece, repeated in the fifth and re-exposed in the twentieth. It also occurs in nos. 6, 10, 11 and 15. Obviously, we needed a visual leitmotiv for this theme, and it had to be a mountain, since the theme is written in mode 2, mainly in the first transposition. Here, the theme is shown along with its colour rendition:

Figure 11 Colour visual of Thème de Dieu, as it appears in ‘Regard du Père’ (Vingt Regards, no. 1).

In no. 5, ‘Regard du Fils sur le Fils’, the same picture is supplied with the addition of the two other layers in the texture of the piece, modes 44 and 63 of the rhythmic canon, respectively to the left and right of the main picture.

In no. 6, it appears at a dramatic climax, described as ‘La face de Dieu derrière la flamme et le bouillonnement (The face of God behind the flames and the boiling)’. Here, a different rock landscape was considered apt.

When the theme returns in no. 20, ‘Regard de l’Eglise d’amour’, the picture from the first piece returns inside a Moorish portal symbolising the universal church. This illustrative deviance from our principles was found admissible at this monumental point in the score.

Figure 14 Colour visual of Thème de Dieu placed inside a Moorish portal at the theme’s return in ‘Regard de l’Eglise d’amour’ (Vingt Regards, no. 20).

Thème d’amour mystique (Theme of mystic love)

Four chords of the Thème de Dieu later become another cyclic theme, called Thème de l’amour mystique or simply Thème d’amour. We chose the image of rhododendrons to illustrate this theme, partly since they contain the blue violet colour of mode 21. The colour of the flowers will change, though, according to the transposition, from golden brown through green to blue violet.

Figure 15 Thème d’amour.

Video 9 Thème d’amour, in ‘Regards du Père’ (Vingt Regards, no. 1).

The theme appears as a separate theme in no. 6, then it reappears in no. 19 where it becomes a major element. In no. 20, the theme undergoes an extensive development, bringing the tension of the piece to almost unbearable heights.

Video 10 Thème d’amour, in ‘Regards de l’Eglise d’amour’ (Vingt Regards, no. 20).

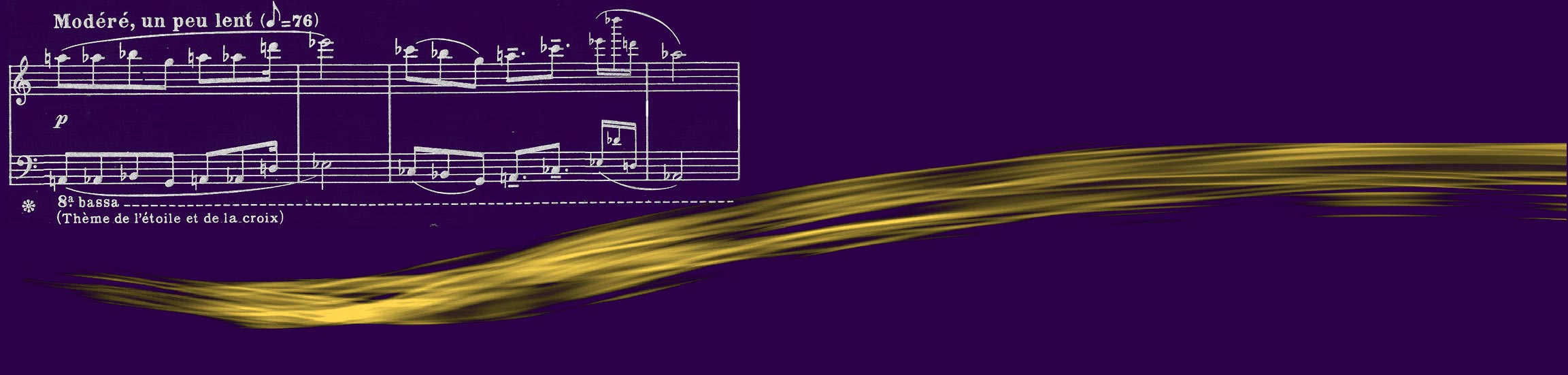

Thème de l’Étoile et de la Croix (Theme of the star and the cross)

The next cyclic theme is that of the star and the cross. As Messiaen states in the preface, they have the same theme since one opens and one closes the life of Jesus Christ on earth.

Figure 16 Colour visual of Thème de l’Étoile et de la Croix as it appears in ‘Regard de l’Étoile’ (Vingt Regards, no. 2).

The theme is rendered with a yellow ribbon on purple background; the colours of mode 43, very close to the mode of this theme, here as it appears in no. 2 (‘Regard de l’Étoile’). In no. 7 (‘Regard de la Croix’), the theme is harmonized in A flat minor and later combined with modes 64 and 46. This adds a combination of shapes and colours. The crystals refer to mode 46, the diagonal banner to mode 64.

Figure 17 Colour visual of of Thème de l’Étoile et de la Croix as it appears in ‘Regard de la Croix’ (Vingt Regards, no. 7).

Thème d’accords (Chord theme)

This theme provides secondary material for many of the pieces. It is first heard in no. 6 as part of the chord progression mentioned earlier (Video 3). The theme itself appears in no. 14, ‘Regard des Anges’, and later in no. 17, ‘Regard du Silence’, in a simultaneous straight and retrograde combination. In both these instances, it is completed by four chords in mode 3, first and third transposition alternating.

Video 11 Thème d’accords in ‘Regards des Anges’ (Vingt Regards, no. 14).

The condensed chords are also used in various transpositions. When these occur, I have deduced the colours from other sources, since they are not described by Messiaen.

Thème de joie (Theme of joy)

This theme appears at a climactic moment in no. 10, ‘Regard de l’Esprit de Joie’. It is stated in various tonalities, harmonized with chords with inversions transposed on the same bass note, somewhat modified, here on the dominant of the tonality in question. Video 12 begins its first statement in A flat with elements listed in Appendix 3. The pictures are shown against a background of a mountain landscape proper to this theme. This first statement is followed by a modulating development where the basic colour of the mountain landscape changes on each chord. Then there is a second statement of the theme in B major, bringing into play a quite different colour spectrum (explained in Appendix 3).

Video 12 Thème de Joie in ‘Regard de l’Esprit de Joie’ (Vingt Regards, no. 10).

Thème du baiser (Theme of the kiss)

The theme of the kiss appears at the climax of no. 15, ‘Le Baiser de l’Enfant-Jésus’, and is harmonized in mode 2 in its three transpositions, corresponding to tonic, dominant and subdominant of F sharp major. Gold is the main colour of this tonality, and the added colour alternates between blue-violet (21 for the tonic), green (23 for the subdominant) and red-brown (22 for the dominant).

Video 13 is compiled of three excerpts from no. 15:

- The opening, a variant of Thème de Dieu as lullaby, using first and second transpositions of mode 2 in a garden scene, corresponding to Messiaen’s description of this scene: ‘At each communion, infant Jesus sleeps with us near the door, then he opens it to the garden and throws himself in full light to kiss us …’41)Subtitle in the score, p. 108: A chaque communion, l’Enfant-Jésus dort avec nous près de la porte; puis il l’ouvre sur le jardin et se précipite à toute lumière pour nous embrasser…

- Page 114, system 2 of the score: Development of Thème de Dieu in canon, all in mode 21 represented by flowing water in blue violet and gold, and white stars. Change at Modéré to rocks juxtaposed to a sequence of coloured shapes appearing at the right, which slide towards the rocks in the crescendo. This corresponds to the two main elements in the music at this point: chords in mode 21 moving upwards, superposed to and interrupted by another chord sequence comprising the chord theme, carillon chords, resonance chords and chords with inversions transposed.

- Page 117, system 3: The kiss (Le baiser), described above.

Video 13 Thème du Baiser in three excerpts of ‘Le baiser de l’Enfant-Jésus’ (Vingt Regards, no. 15).

The theme of the kiss returns in no. 19, ‘Je dors, mais mon cœur veille’, where it constitutes one of the two main themes, the other one being the Theme of Love.

Geometric canvasses

In the software version we used for the Vingt Regards, it was possible to change between different shapes of the virtual projection canvas. In addition to the rectangle, we could use the sphere, cylinder, cone and other shapes, which extended our possibilities for visualisation. Two examples from no. 4, ‘Regard de la Vierge’, will illustrate this. The first, shown in the upper half of Figure 19, accompanies the polymodal passage in bar 41, and has 3 layers:

Figure 19 Colour visuals of ‘Regard de la Vierge’ (Vingt Regards, no. 4); the polymodal passage at bar 41 (upper half) and a passage at bar 62 (lower half).

The main theme of this passage, derived from Theme of the Star, a ribbon coloured light violet and here represented by the c sharp octave. The chords in the left hand in mode 31 (orange sheet with drawings of gold and milky white, and some spots of ash grey) the chords in the right hand in mode 45 (intense violet, with grey mauve zones).

The second example, in the lower half of Figure 19, illustrate the short passage in bar 62, with the same theme (derived from the Theme of the Star) in the left hand and a turning, sparkling figure in mode 33 (green and blue) in the right hand. One could obviously choose other forms; the choices were made from the character of the music and the visual aesthetics.

No. 17, ‘Regard du silence’, referred to in the beginning of this article, is described in Appendix 1. Video 1 shows the first half of this piece.

As a final example from this visualisation of the Vingt Regards, Video 14 shows the first part of no. 13, ‘Noël’. The description of the events in this passage is given in Appendix 4.

Video 14 The first part of ‘Noël’ (Vingt Regards, no. 13).

It is obvious that a description all the processes and choices in this two-hour cycle would exceed by far the scope of this article. We hope the examples give a fair impression of the work.

Final remarks

‘It is odd for a composer to explain the sources of his language by speaking first of all about colour’ (emphasis added), Messiaen told Claude Samuel in one of their conversations.42)Samuel, Entretiens, p. 21 Indeed, Messiaen’s almost inexhaustible wealth of chord constructions is so closely related to his synaesthetic colour hearing that ignoring this relation in favour of other theories will fail, comparatively, to explain his harmonic inventiveness and identify the foundation for his harmonic imagination.

In the introduction to his recent study, Gareth Healey discusses the insufficiency of Messiaen’s writings when it comes to analysis:

A vital step towards autonomous analysis is developing knowledge gleaned from Messiaen’s treatises into an instinct for what he might do at any given point in a work. On countless occasions rhythms or harmonies are encountered which don’t ‘fit’; for example, a chord may bear no obvious relation to any defined element of his musical language. At such moment alternative strategies must be employed in order to make sense of the chord, and an answer can only be arrived at after a prolonged study of the composer’s way of working.43)Healey, Messiaen’s Musical Techniques, p. 1.

Indeed, Messiaen himself says: ‘Je n’ai pas tout dit (I have not said everything)’.44)Tournelle, Pierre: ‘Olivier Messiaen – Le Prêche aux Oiseaux’, in Diapason-Harmonie, 344 (Dec., 1988), p. 77. Working on his music, I could reveal some of these ‘secrets’, but some of his choices are guided by intuition, rather than by absolute submission to his own rules, when these rules would yield a result that ‘doesn’t sound’. After my prolonged studies with and of Messiaen – his writings and above all his music – I can only hope that my ‘instinct’ has not deceived me when co-creating a visual extension of his works in the form of colour analyses.

Messiaen told me, when we discussed his synaesthesia in 1988, that everyone should see his or her own colours, since the experience of colours with music is so subjective. He also says, discussing the phenomena of ‘synopsia’:

Do synoptics exist? Are all men and women synoptics? I think one can answer yes all along. Adding that (for the time being) we talk about a badly controlled relationship, variable from one individual to another, and entirely subjective.45)Traité, vol. 7, pp. 97–8: ‘Existe-il des synoptiques? Tous les hommes et les femmes sont-ils synoptiques? Je pense qu’on peut répondre oui sur toute la ligne. En ajoutant qu’il s’agit (pour l’heure) d’un rapport mal contrôlé, variable suivant les individus, et entièrement subjectif.’

Why, therefore, do I not try to render my own colours rather than his? First, I do not by far possess the ability to discern colours as precisely as did Messiaen, but second, and above all, Messiaen’s own visions, so minutely described in his writings, constitute the only authentic source for re-creating the visualisation. At several points in his life, Messiaen gave accounts of how he perceived the connections between the modes, as well as certain chords, and complexes of colours. It is worth noticing that these descriptions are subject to hardly any variation at all; if anything, they became more detailed over the years. That in itself proves the significance of the colours to the composer and the continuous presence of this subject in his mind.

My hope was that showing his colours in a concert situation would open up for this dimension in the listener. The performances in Oslo were unfortunately not reviewed in the press, but they provoked many reactions, spanning from those who found the experience of the colours a real enhancement to the musical experience to those who found them rather disturbing. The purpose of the project was indeed to discover whether visualisation is justified and acts as an artistic enhancement, and the conclusion must be that this was the case for many people, if not for everyone. Many people were able to open up, but some of these would rather see their own colours than the ones proposed. This is, in fact, according to Messiaen’s own wish. Still others, however, reacted with some hostility. The former group indeed experienced seeing the colours as enrichment to hearing the music, the latter would rather do without.

Whether the latter group was subject to prejudice, is difficult to say. For the majority of people, I think this project can bring a greater dimension to understanding Messiaen’s music. I base this assumption, though, merely on sporadic feedback from the public. It would have been interesting to make an enquiry among those present, but we lacked the resources to do this.

Colour hearing, a direct result of Messiaen’s faculty of synaesthesia, shaped his works in a fundamental way along with birdsong and religious themes, which were all subject to Messiaen’s ‘colourations’. We haven’t even touched upon his notion of rhythm, being ‘colouring of time’. The growing awareness of these connections has certainly made its mark on my interpretations of Messiaen’s works, which have been on my repertoire for so long. This has been a very gradual process, which started long before this project was commenced, but working on the project has indeed enhanced my perception of Messiaen as perhaps the most central composer of the twentieth century. He gathered threads from the past and from other cultures, re-questioned their significance and shaped his own, very personal musical universe, based on his new concepts of time and space. Without imposing his own style on others, he then transmitted his knowledge to his students and thus played a decisive role in the formation of several generations of composers.

Appendixes

Appendix 1

Description of events and explanation of the colour visuals in Video 1, ‘Regard du Silence’:

… every silence of the cradle reveals musics and colours that are the mysteries of Jesus Christ…46)Subtitle in the score: …chaque silence de la crèche révèle musiques et couleurs qui sont les mystères de Jésus-Christ….

- Bars 1–19: A rhythmic canon with the chords of the left hand in mode 44 (like petunia flowers: dark violet, white with violet designs, purple violet) surrounding the chords of the right hand in mode 34 (background: large sheet of orange, strongly striped with red, finely striped with blue. Branches in blue, violet purple, and silver – white lilies, tiger lilies with cinnabar red flowers punctuated with black – fruits in orange and blue, fruits in orange and green).

- Bars 20–26: A chordal passage with the succession of:

- Bar 20: two chords in mode 42 and 46 (crystal reflections),

- Bar 21: the chords with inversions transposed no. 8A and 8B (described above),

- Bar 22: the condensed chord theme (described above),

- Bar 23: the chords with contracted resonance I no. 1A (yellow, mauve violet, leaden grey) and 1B (bluish green, violet, leaden grey), and

- Bar 24: the chords with contracted resonance II no. 11 A–B (high wall of grey stone, with some spots of pale orange and mauve, a green zone, and remnants of black).

All these are shown in different geometric shapes.

- Bars 27–29: A sequence of chords in mode 33 (described above). This rendering of mode 33 is shaped like a cylinder because of the turning motion of the chords.

- Bars 30–36: A passage in mode 22 (described above), in the shape of a cave.

- Bar 37 (Modéré, Presque vif): A glittering passage with chromatic patterns in the right hand and chords in mode 44 (described above) in the left.

- Bars 38–39: An alternation of chords with inversions transposed, nos. 8 A–B and 4 A–B, described elsewhere, and also shown in Video 2, here in a cylindrical shape.

- Bar 40: Arpeggio figurations in mode 31 (orange with gold and milky white).

- Bars 41–44 (Bien modéré): A mirror by retrograde, mentioned elsewhere, of the extended chord theme; the effects of mirroring are visualized.

- Bars 45–52: A succession of short splashes of colours:

- 45: mode 33,

- 48: chords with contracted resonance II no. 11 A–B, and

- 49: mode 22; all these colours have been seen (heard) before.

Appendix 2

Descriptions of events and explanation of the colour visuals in Trois Petites Liturgies, first movement, corresponding to Video 7 at 2:08, corresponding to bar 40 in the score.

- chord with inversions transposed no. 4A (vertical ribbons: green, violet, dark blue) – bar 40, piano, celesta, strings

- mode 21 (blue violet rocks) – bar 40, choir

- mode 33 (blue, green with red orange lilies) combined with mode 46 (reflections: carmine red, violet purple, orange, grey mauve, grey pink) – bar 42, piano right hand and celesta, piano left hand and pizz.

- mode 41 (grey blue (present in the landscape), gold (shown as lilies)) – bar 45, violin solo

- mode 61 (large golden letters on grey background, with orange pastille spots, and rather dark green branches with golden reflections) superposed on mode 32 (horizontal stripes going up, from bottom to top; dark grey, mauve, light grey, and white with mauve and pale yellow reflections – with golden flaming letters in an unknown writing (these letters common with mode 61)) – bar 50, piano right hand and vibraphone, piano left hand and pizz.

Appendix 3

Descriptions of events and explanation of the colour visuals in Video 12, Thème de Joie, page 69 in the score:

- G Major (yellow) – Ab Major (sapphire blue)

- Dominant 7th of Ab Major with suspension on Ab (pink) – Dominant 7th of A Major (red)

- Chord A-C-Eb-Bb (pale violet) – Minor 7th chord on Bb (mauve)

- A# Major (red grey) – B Major (brown)

- Dominant 7th of B Major with suspension on B (brown) – Dominant 7th of C Major (yellow white)

- Chord B#-D#-F#-C# (green blue) – Minor 7th chord on C# (red brown)

First statement on an alternation of the following chords:

– Chord with transposed inversion no. 3A (Mauve campanulas on white and light grey veils)

– No. 3C (violet-orange iris on turquoise background)

Modulating commentary (bar 1–4 of Encore plus modéré on p. 69) using these combined tonal harmonies):

| Right hand | Colour | Left hand | Colour | |

| a | G major | Yellow | Ab major | Sapphire blue |

| b | Eb7 sus 4 (dominant of Ab) | Pink | Fb7 (E7) (dominant of A) | Red |

| c | A-–C-–Eb (with either Bb or G) | Pale violet | Bb minor 7 | Mauve |

| d | A# major | Red grey | B major | Brown |

| e | F#7 sus 4 (dominant of B) | Gold | G major 7 (dominant of C) | Yellow white |

| f | B#–-D#-–F#-–C# | Green blue | C#minor 7 | Red brown |

The harmonies come in the following order (starting at Encore plus modéré):

a–b–c–b–a–b ⎜ c–b–a–b–c ⎜ d–e–f–e–d–e ⎜ f–e–d–e–f

Second statement of the theme (at Trés modéré, Tempo rubato) with the following chords:

– Chord with transposed inversion no. 6A (copper, gold and brown, red with black)

– No. 6C (flaming gold stars – on crystals burnt earth, reddish brown and leather, with amethyst violet and light Chartres blue).

Appendix 4

Description of events in Video 14, Vingt Regards no. 13, ‘Noël’:

- Carillon, rendered with a pan of a mountain landscape, interspersed with lightning flashes. No specific colours here, only descriptive of the music’s character.

- Bar 6: The landscape turns violet. Here, a coagulation of mode 43 (violet, yellow) constitutes the first chord, while a condensation of the chord theme is heard in the treble, the colours of these two chords – Steel blue grey crisscrossed with red and orange, mauve violet spotted with leather brown, circled with purple – being rendered in the lightning (red, orange) and in the violet of the landscape.

- Bar 8: A chord very similar to the second contracted resonance chord, no. 8 accounts for a big mauve zone. Emerging from this: columbines (yellow and mauve), irises (yellow and mauve), nasturtiums (red orange), and in the middle a gold star. This picture is projected on a cone at the lower left side of the picture. To the right, illustrating the xylophone theme in the treble, a picture of mode 66: vertical black and white banners scattered with pale blue moons.

- Bar 10: Chord theme, fractioned version of the condensation in bar 6. Here the ‘lightning version’ of this theme is projected in an open cylinder.

- Bar 13: Return to the picture of bar 8.

- Bar 15: First contracted resonance chord, no. 1A (yellow, violet, leaden grey), projected on a reversed cone, with four pitches added in the treble, rendered with movement at the edge of the cone.

- Bar 17: First contracted resonance chord, no. 1B (bluish green, violet, leaden grey), in the same manner as 6.

- Bar 18 (Au mouvement): same as 3.

- Bar 20: Chord theme transposed – chord B from Theme d’accords, transposed to F (milk white spotted with green, circled mauve, rose), the green formed as a turning cross.

- Bar 21: same as 1.

- Bar 26: Passage in mode 31 (Orange sheet with drawings of gold and milky white, and some spots of ash grey). This picture is based on a video of melting ice on a lake.

Footnotes

References