“That it´s not too late for us to have bodies”

Notes on Extended Performance Practices in Contemporary Music

Read as PDF

Table of Contents

DOI: 10.32063/0602

Monika Voithofer

Monika Voithofer is a PhD Candidate in Musicology at the University of Graz. She studied Musicology (BA, MA) and Philosophy (BA) at the Universities of Graz and Vienna and completed her MA at the University of Music and Performing Arts Graz with an award-winning thesis on the role of female artists within the International Society for Contemporary Music. In her dissertation she scrutinizes conceptual music and its entwined history with conceptual art practices. To this end, she is currently pursuing research at several institutions located in London, New York City and Chicago. Her academic work is focused on music aesthetics, twentieth century avant-gardes and contemporary music/art in the twenty-first century.

by Monika Voithofer

Music & Practice, Volume 6

Performative Compositional Practice

When Performance became a Genre of Art

In the summer of 1952 in post-war Europe’s avant-garde music centre, Darmstadt, whose summer courses have been taking place since 1946, the predominating compositional style was serialism, represented by composers such as Pierre Boulez, Luciano Berio and Karlheinz Stockhausen.[2] On the East Coast of the United States of America, on the other hand, completely contrary musical tendencies were being developed, with composer John Cage as one of the central figures behind them. An initial event that is still today considered a trendsetting moment took place in the dining room of Black Mountain College (North Carolina). Composers John Cage and Jay Watts, pianist David Tudor, dancer Merce Cunningham, painter Robert Rauschenberg and poets Charles Olsen and Mary Caroline Richards were involved. This would go down in history as the Untitled Event. The actions of this event were conceived very vaguely. The performers merely had a kind of ‘score’ in which, by means of ‘time brackets’, the duration of the various actions was indicated:

In this way there would be no casual ‘relationship’ between one incident and the next, and according to Cage, ‘anything that happened after that happened in the observer himself’.[3]

After Cage read a text on ‘the relation of music to Zen Buddhism’ and excerpts from Meister Eckhart, he performed ‘a composition with a radio’; then Tudor played a prepared piano, while Rauschenberg simultaneously played old recordings on a gramophone. Moreover, Rauschenberg’s White Paintings were exhibited. At some point, Tudor poured water from one bucket into another; Cunningham danced and poems were read, among many other actions. The seats for the audience were arranged opposite one another, in the form of four triangles, and white cups were placed on the chairs.[4]

The country audience was delighted. Only the composer Stefan Wolpe walked out in protest, and Cage proclaimed the evening a success. An ‘anarchic’ event; ‘purposeless in that we didn’t know what was going to happen’, it suggested endless possibilities for future collaborations.[5]

For Erika Fischer-Lichte, viewing it in retrospect, the Untitled Event represents in several respects a remarkable turning point in the history of theatre in Western culture: It not only redefined the relationship between actors and spectators at a performance – the audience became a co-creative entity – but also pioneered the involvement of different art categories in one performance. The Untitled Event radically questioned the hitherto convention-bound concepts of theatre, art and culture and opened up perspectives for a different understanding of these media.[6] By dissolving the boundaries of the different art categories – such as poetry, visual art or music – and transforming their artistic objects into actions, everything merged into everything else as ‘performance art’. As Fischer-Lichte argues, the performative process became constitutive in a specific way of perceiving space, in a particular body sensation, in a certain form of time experience and in a new value of materials and objects.[7]

The Untitled Event can undoubtedly be seen as a significant occasion in regard to the development of performance art as a new, self-contained genre of art in the 1960s. However, the musicologist Christa Brüstle remarks, rightly, that, deriving the whole range of new performative developments of performance art in the 1960s solely from it not only narrows the musical perspective, but also puts the history of theatre in the twentieth century on a strangely narrow path.[8]

Fluxus

One symptom of the wider pattern of influence that is closer to the reality of the situation is the way the American post-war avant-garde of the 1950s and 1960s rediscovered historical avant-garde movements that had taken place in Europe in the beginning of the twentieth century and adapted them for their own use, re-evaluating them in a different social, historical and geographical context.[9] John Cage himself was heavily influenced by Dadaism and by the conceptual approaches of early twentieth-century artists and composers such as Marcel Duchamp, Erik Satie and Charles Ives. In his role as a teacher at the ‘New School of Social Research’ in New York City, Cage, in turn, influenced a whole generation of students such as Dick Higgins, Al Hansen and Allan Kaprow, among others.[10]

Fluxus, as a movement, developed in the area of the U.S. East Coast, especially in New York City in the early 1960s. Yoko Ono, George Brecht, Nam June Paik and Takehisa Kosugi, who organized the first Fluxus events in Tokyo in 1960 with the Ongaku group, became important figures of Fluxus.[11] However, it is George Maciunas who is considered as the main initiator, main protagonist, and, above all, the main publisher of the Fluxus movement.[12] Maciunas pointed out that, whether via Cage or through direct influence, Fluxus has to be seen in close relation to the artistic practices of historical avant-garde movements such as Dadaism or Futurism as well as to Duchamp’s Ready-mades.[13]

One of Fluxus’ key aims was to dissolve the separation of art and life. Again, this connects to ideas propounded by Cage and is often expressed in musical terms. Composer Michael Nyman speaks of Cage’s ideal ‘[…] of a music which attempts to remove the distinctions between life and art […]’.[14] Furthermore, Fluxus member Ken Friedman emphasizes the important role of music within the group’s artistic practice:

Musicality is a key concept in Fluxus. It has not been given adequate attention by scholars or critics. Musicality means that anyone can play the music. If deep engagement with the music, with the spirit of the music is the central focus of this criterion, then musicality may be the key concept in Fluxus.[15]

According to the Fluxus way of thinking, everything can be music. So-called ‘Event Scores’ and ‘Instruction Pieces’ – mostly linguistic instructions for performances that involve activities and objects from everyday life – form the basis for the artistic practice of Fluxus.[16] Following this philosophy, anyone can become an interpreter and performer of pieces. Examples that embody this principle include Yoko Ono’s famous Cloud Piece (1963) ‘Imagine the clouds dripping. Dig a hole in your garden to put them in’ from her 1964 published artist’s book Grapefruit, Alison Knowles’ #7 Piece for Any Number of Vocalists (1962) ‘Each thinks beforehand of a song, and, on a signal from the conductor, sings it through’ and Dick Higgins Danger Music #17 (1962) ‘Scream ! ! Scream ! ! Scream ! ! Scream ! ! Scream !! Scream ! !’.

Intermedia Art

Dick Higgins featured not only as an artist, but also as a publisher in the context of Fluxus. Founded in New York City, and active during the period from 1964 to 1974, his Something Else Press published books and pamphlets on the movement in order to make its then unconventional artistic practices accessible to a wider audience.[17] In one of his articles, written in 1965, he coined the term ‘Intermedia Art’. The famous and much-cited opening sentence of this article states: ‘Much of the best work being produced today seems to fall between media’.[18]

Intermedia Art refers to a then new art form, in which what were formerly different kinds of media and genres are merged into one another. As a result, the nature or the ontology of the art object changes: it is this conception of art no longer as an object but, rather, as a fluid process that constitutes the essence of Intermedia Art:

Thus the happening developed as an intermedium, an uncharted land that lies between collage, music and the theatre. It is not governed by rules; each work determines its own medium and form according to its needs. The concept itself is better understood by what it is not, rather than what it is. […] However, I would like to suggest that the use of intermedia is more or less universal throughout the fine arts, since continuity rather than categorization is the hallmark of our new mentality. There are parallels to the happening in music, for example in the work of such composers as Philip Corner and John Cage, who explore the intermedia between music and philosophy, or Joe Jones, whose self-playing musical instruments fall into the intermedium between music and sculpture. […] Is it possible to speak of the use of intermedia as a huge and inclusive movement of which dada, futurism and surrealism are early phases preceding the huge ground swell that is taking place now? Or is it more reasonable to regard the use of intermedia as an irreversible historical innovation, more comparable, for example, to the development of instrumental music than, for example, to the development of romanticism?[19]

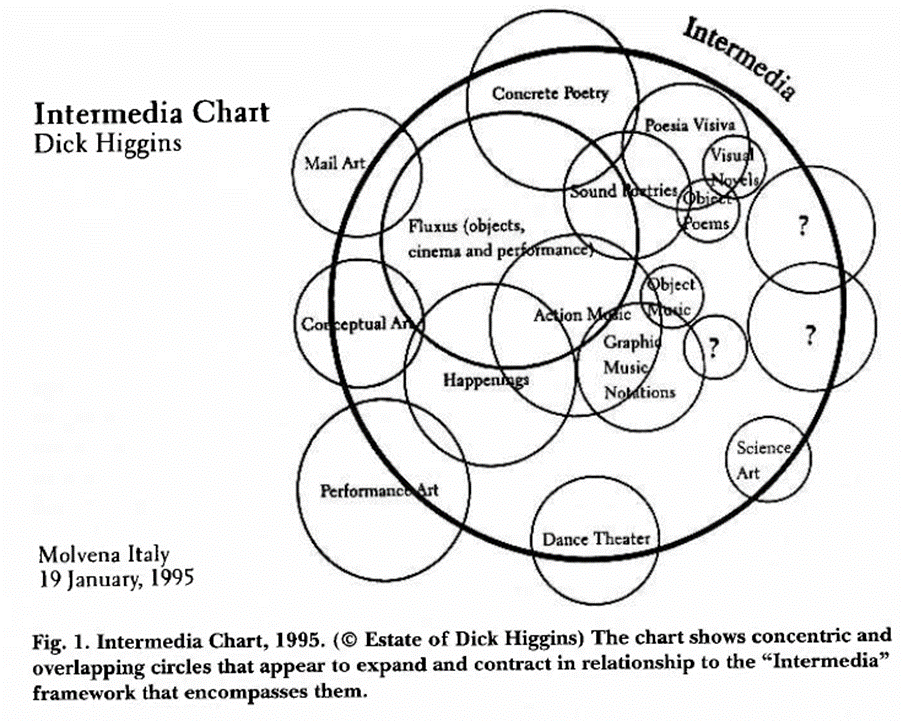

As an illustration, and looking back from the somewhat later vantage point of 1995, Higgins also created the following chart:[20]

Hannah Higgins, art historian and daughter of Dick Higgins describes the chart as follows:

Fluid in form, the chart shows concentric and overlapping circles that appear to expand and contract in relationship to the ‘Intermedia’ framework that encompasses them. It is an open framework that invites play. Its bubbles hover in space as opposed to being historically framed in the linear and specialized art/anti-art framework of the typical chronologies of avant-garde and modern art.[21]

As an umbrella term for closely related art practices that are characterized by the interdependency of different media – such as Conceptual Art, Performance Art or the activities of Fluxus – Intermedia Art signifies a range of practices that emerged, above all, as a reaction against the essentialist tendency in modernism. Conceptual Art for example rejected the formalist concept of modernity that Clement Greenberg – one of the most influential U.S. art critics and a staunch advocate for the pure medium – had developed.[22] The philosopher Peter Osborne specifies the rejection of four particular aspects demanded by Greenberg in regard to modernist painting: material objectivity, medium specificity, visuality and autonomy.[23] I shall return to these later in the article.

In Conceptual Art, or in Intermedia Art practices more generally, ‘[…] the critical destruction of medium as an ontological category was the decisive, collective historical act […]’.[24] In this context, it is important to clarify the use of the term ‘medium’, since there is no universal definition for the term. In this article, the concept of media is not reduced to a narrow technical determinism in the sense of media as mere instruments or apparatuses for the transmission and distribution of communication structures. Rather, a broader understanding of the term, including implicit knowledge of institutions, programmes, discourses, formal strategies, practices and other heterogeneous networks, is adopted.[25]

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, media have themselves become malleable materials in artistic processes. Especially since the digital transformation and the associated separation between analogue and digital media, completely new and contradictory positions have emerged – with regard to artistic forms as well as media – that need to be critically addressed.

The Digital Transformation and its Impact on Contemporary Music

The cultural sociologist Andreas Reckwitz identifies a total of three specific media transformations: he sees the first as occurring in the period of early bourgeois modernity with the invention of the printing press and, thus, the spread of the medium of writing. In a second transformation, during the organised modernism of first two decades of the twentieth century, he notes the triumphal march of audiovisual media and the way that film, in particular, took hold. The most recent media transformation – that of late-modernist and postmodern times since the 1970s and 1980s – involves novel digital practices, made possible through the medium of computer, and, for Reckwitz, entails a complete ‘transformation of the structure of sensory perception’ in the context of postmodernity.[26] This latest, digital media transformation represents a ‘last structural as well as cultural epochal threshold’ and marks a ‘significant break between analogue modernism and digital postmodernism’:[27]

The computer confronts the subject with the constellation-like overabundance of visual and written signs, a hypertextual opulence of semiotic possibilities. Unlike with a book or with film, here there is insecurity and a compulsion for connectivity, and thus a competition for attention.[28]

Consequently, digitization has also had a significant impact on intermedia art strategies in contemporary music. Dealing with all kinds of media becomes the subject of reflection in the works themselves. Musicologist Marion Saxer calls it a ‘media-reflective composition strategy’ – the medial arrangement of the setting becomes an integral component of the composition.[29] The media world, especially the virtual media world, is increasingly permeating everyday life. Our life becomes the subject of theatricalization and cultural staging, according to Fischer-Lichte.[30] These circumstances also prompt a re-evaluation of corporeality and its relationship to both the real and virtual worlds.

The valorisation of the body and of physicality is similarly noticeable in certain works of contemporary music. ‘Performance’ here no longer just refers to means of musical interpretation of a self-contained musical work that consists of the pure medium of sound. Rather, in certain pieces of contemporary music, an extension of the term ‘performance’ to encompass visual moment can be seen, in which the staging of the performance is conflated with the audible moment.[31]

The New Discipline

In 2016, Jennifer Walshe wrote a much-acclaimed text for the programme notes of the Norwegian Borealis Festival, entitled ‘The New Discipline’. In it, she states the following:

The New Discipline is a term I’ve adopted over the last year. The term functions as a way for me to connect compositions which have a wide range of disparate interests but all share the common concern of being rotted in the physical, theatrical and visual, as well as musical; pieces which often invoke the extra-musical, which activate the non-cochlear. In performance, these are works in which the ear, the eye and the brain are expected to be active and engaged. Works in which we understand that there are people on the stage, and that these people are/have bodies.[32]

Walshe’s compositions, characterized by the interdependency of different analogue and digital media and the revaluation of the body and physicality, call for a multisensory, instead of a merely auditory, perception. In her Borealis text, she emphasizes the direct reference of her work to certain artistic traditions of historical European and U.S. post-war avant-garde movements such as Dada, Fluxus, Situationism or Mauricio Kagel’s concept of ‘Instrumental Theatre’. At the same time, she insists that it must not be misleadingly categorized into one of these historical genres. The New Discipline is something decidedly new – in particular because of the digital transformation and related socio-cultural developments that enable new technological means of production, distribution and perception:

New Discipline works can easily be designated, even well-meaningly ghettoised, as “music theatre”. While Kagel and others are clear ancestors, too much has happened since the 1970s for that term to work here. MTV, the Internet, Beyonce ripping off Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Stewart Lee, Girls, style blogs and yoga classes at Darmstadt, Mykki Blanco, the availability of cheap cameras and projectors, the supremacy of YouTube documentations over performances. Maybe what is at stake for the New Discipline is the fact that these pieces, these modes of thinking about the world, these compositional techniques – they are not “music theatre”, they *are* music […].[33]

The term ‘New Discipline’ can serve as a descriptor for the working methods of both the composer and the performer. It is at one-and-the-same time a concept and a practice. In many of her works, Walshe herself appears as a vocal performer. Thus, she can be labelled as a ‘composer-performer’. This is a term first mentioned in the second half of the 20th century and denotes the merging of the once separate (although, prior to the early 19th century, largely undifferentiated) identities of composer and performer. It signifies that, through the need to integrate new, expanded instrumental and media technologies into compositions, composers have once more become the performers of their own works.[34]

In addition to sound, three key aspects are central in works related to the New Discipline: body, theatricality and visuality. Walshe does not want to understand the term as denoting an aesthetic movement, style or genre, but rather simply as evoking music that questions what is considered a ‘normal’ or ‘traditional’ composition. Nevertheless, she mentions Matthew Shlomowitz, Neo Hülcker and Steven Takasugi as examples of composers who work in similar ways.[35] The New Discipline is an intermedia art practice, since it integrates various media such as dance, theatre, film, video, the visual arts, installations, literature and even stand-up comedy. Music here is no longer autonomous; it is interdependent with the others arts, and defiantly so. In particular, the digital transformation influences and offers new possibilities of interweaving these various media.

The New Discipline also demands rigour and stringency in the ways of working with all the various media. It requires multiple talents of a single artist. As Walshe says:

I realize the video parts in my work myself. Primarily this is because I want them to be an integral part of the composition – I wouldn’t outsource the cello part in a string quartet to someone else (unless that was the concept of the piece!) so why would I outsource the video part?[36]

It follows from this that, for composer-performers who work with different media and with materials that require extended performance practices in contemporary music, it is no longer enough to learn the ‘craft’ of composing; over and above this, it becomes necessary to acquire a mass of other technical skills, such as the use of video editing software, VJ tools, film cameras, stage and lightning technology, programming, working with microprocessors or even soldering auto-didactically, as the composer Marko Cicliani points out.[37]

In the final section of this article, some specific works by Walshe will be discussed to demonstrate the influence of avant-garde movements upon, and their (digital) continuation in, the New Discipline, referring to extended performance practices in contemporary music, where sound is still a crucial, but not the only, medium.

In her artistic practice, Walshe combines the tradition of European music theatre since Kagel and Dieter Schnebel with that of American experimental music since the 1950s, embracing everything since John Cage from movements such as Fluxus and Happening to Performance and Conceptual Art and transferring and expanding these influences into the digital realm in terms of production, distribution and perception.[38] She is particularly interested in the Web and places herself in the tradition of net art and post-internet art. In the former, the virtual space becomes a place of artistic creation, while the latter questions in an artistic manner the social impact of the internet.[39] In THMOTES (2013), for example, she sent text scores via Snapchat. Looped GIFs form the visual elements of the ephemeral scores. In another project, she uses stochastic processes to generate a constant stream of scores, tweeting the results on @SuperSuperThank. This means that, as a composer, she gives up control of all creative parameters and the result is indeterminate.[40]

Walshe’s text scores can clearly be seen in the tradition of Fluxus and Conceptual Art, but in her case they are linked to everyday digital life. Within a high-tech language, she reflects socio-cultural questions raised by the digital ecosystem of the Web 2.0.

I feel we’re missing out on a rich engagement if we fail to let text scores be affected by the language of the times we live in. I want text scores which are warped by Twitter and Flarf, bustling with words from Merriam-Webster’s Time Traveller, experimenting with language in the way Ben Marcus and Claudia Rankine do. If, as Donna Haraway says, “Grammar is politics by other means”, why not take the opportunity to interfere?[41]

The use of Web 2.0 is omnipresent in Walshe’s artistic strategies – for example, when she posted “ASMR” (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response) videos – videos that produce certain “feel-good” stimuli through sounds – on the YouTube channel ‘softsoftmusic ASMR’[42]

Walshe subsequently used these ASMR videos for her piece THE TOTAL MOUNTAIN, which was premiered at the Donaueschingen Festival in 2014. In this approximately 40-minute long, intermedia, one-woman performance, she is on stage next to video projections and other objects. The internet, an immersive, identity-creating memory space, and its everyday, self-evident handling is central in the piece. Among other things, Walshe recites various tweets (statements published on the short message service Twitter) in a video.[43]

Overloaded with everyday objects, the video reinforces Walshe’s artistic statement of the Internet as a mass medium of the so-called ‘information society’, in which facts and fake news seem difficult to separate. A sheer flood of images and actions breaks in on the audience. The performance becomes a medial overkill for the observers. THE TOTAL MOUNTAIN works with strategies that recall Andreas Reckwitz’ statement in regard to the digital transformation, quoted above, in their ‘overabundance of visual and written signs’, their ‘hypertextual opulence of semiotic possibilities’ and their ‘compulsion for connectivity, and thus […] competition for attention’.[44]

Walshe is also interested in Artificial Intelligence (AI); as a composer of the 21st century, she sees it as a matter necessity to deal with AI and neural networks:

This blows my mind. Hidden layers of calculations. Neurons buried in vast amounts of code, creating and defining emergent concepts. And us, we puny humans, getting to witness new forms of thinking. New forms of art.[45]

Digitization is currently putting art at a crossroads and Walshe wants to contribute to shaping the direction it will take. Together with Memo Akten, a specialist in the field, she has developed “Granma” (Granular Neural Music & Audio), a folding neural network.

For this project, Walshe sits in front of the laptop and films herself while improvising. Based on this, Memo Akten generates the neural network with the goal that “Granma”, together with Walshe, will produce both audio and video parts for a performance situation. Her voice will no longer be live-synthesized with midi or sampling, but with the network. The result is indeterminate and unpredictable. Walshe envisions: “A new strange sibling, both of us together in the uncanny valley on stage”,[46] The result is ULTRACHUNK (2018) – an interactive audiovisual duet in real-time between Walshe and “Granma”.

Conclusions on the Scope of Performance Studies in Musicology

The intermedia and performative developments in artistic practices in the field of contemporary music since the 1950s, which are outlined in this article, draw attention to one desideratum in particular: musicology must respond to these developments. Intermedia art practices in the 1960s and 1970s, from Fluxus to Conceptual Art, emerged as a rejection of the concept of the ‘pure medium’ residing separately in different art genres.[47] The extended performance practices of contemporary music can be seen as echoing the rejection, cited above, by Peter Osborne of four aspects in particular: they break free from material objectivity, from medium specificity, from audibility (instead of Osborne’s visuality) and from autonomy.[48] In extending the traditional understanding of a musical artwork, they rehabilitate the role of the body and of physicality owing to their intermedia and performative concert-settings. In such environments, the various media of artistic practices are no longer just means to an end, but come into focus, in particular, upon the body as the medium in which they are united.[49]

It is partly because of this embodied focus that cultural questions about identity and rituals have also become important in the analysis of contemporary works that employ extended performance practices.[50] For example, the philosopher Sybille Krämer states that the performance of the voice is identity-creating – it is a trace of the body in the language, it expresses the unsayable.[51] Walshe shares this awareness:

Gender, sexuality, ability, class, ethnicity, nationality – we read them all in the voice. The voice is a node where culture, politics, history and technology can be unpacked.[52]

Cultural studies related aspects must be considered as well when attempting an analysis of Walshe´s works with questions beyond those relating to aesthetic claims, asking not just how but why she uses a range of technical reinforcements such as (contact-) microphones, samplers, vocoder, autotuner and other effects in her vocal performances.[53] Just as the composer-performer working in a multimedia context must be appropriately multi-skilled, the same requirement applies to the critic or scholar commenting upon the works produced in this milieu. The ‘performative turn’, proclaimed in the field of cultural studies at the end of the 1990s, made the concept of performance an umbrella-like one under whose span are included both performativity and staging. In this context, the question of mediality and the materiality of performative acts of embodiment in diverse media becomes a central one.[54] Even assuming that they still employ something resembling a score, the analysis of intermedia and performative works of contemporary music purely on the basis of their supposed identity as autonomous musical works is clearly insufficient. When analysing extended performance practices in contemporary music, the definition of the term performance, the scope of what is understood by performance studies and the range of tools available to the analyst must all be correspondingly expanded if the field of musicology is to keep pace with that of the performances it purports to study.[55]

References

Brüstle, Christa, Konzert-Szenen, Bewegung, Performance, Medien. Musik zwischen performativer Expansion und medialer Integration 1950-2000, (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2013), [Beihefte zum Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 73]

Brüstle, Christa, article on ‘Performance‘, in Jörn Peter Hiekel and Christian Utz, eds, Lexikon Neue Musik, (Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, 2016), pp. 503-506

Ciciliani, Marko, ‘Music in the Expanded Field – On Recent Approaches to Interdisciplinary Composition’, in Michael Rebhahn and Thomas Schäfer, eds, Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik 24, (Mainz: Schott Music, 2017), pp. 23-35

Drees, Stefan, Körper, Medien, Musik. Körperdiskurse in der Musik nach 1950, (Hofheim: Wolke Verlag, 2011)

Fischer-Lichte, Erika, ‚Grenzgänge und Tauschhandel. Auf dem Weg zu einer performativen Kultur‘, in Uwe Wirth, ed., Performanz. Zwischen Sprachphilosophie und Kulturwissenschaften, 6th ed., (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2015), pp. 277-300

Friedman, Ken, ‘Fluxus and Company’, in Ken Friedman, ed., The Fluxus Reader, (Chichester: Academy Editions, 1998), pp. 237-253

Goldberg, RoseLee, Performance Art. From Futurism to the Present, 3rd edition, (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2001)

Higgins, Dick and Hannah Higgins, ‘Intermedia’, in: Leonardo 34/1 (2001), p. 49-54

Schröter, Jens, ‘Das ur-intermediale Netzwerk und die (Neu-)Erfindung des Mediums im (digitalen) Modernismus. Ein Versuch’, in Joachim Paech and Jens Schröter, eds. Intermedialität Analog/Digital. Theorien – Methoden – Analysen, (München: Wilhelm Fink, 2008), pp. 579-601

Katschthaler, Karl, From Cage to Walshe: Music as Theatre, in Fiona Jane Schopf, ed., Music on Stage, (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015), pp. 125-139

Kloos, Franziska, Jennifer Walshe. Spiel mit Identitäten, (Hofheim: Wolke, 2017)

Knapstein, Gabriele, artcile on ‘Fluxus‘, in Hubertus Butin, ed., Begriffslexikon zur zeitgenössischen Kunst, (Köln: Snoeck, 2014), pp. 89-93

Krämer, Sybille, ‘Was haben ‚Performativität‘ und ‚Medialität‘ miteinander zu tun? Plädoyer für eine in der ‚Aisthetisierung‘ gründenden Konzeption des Performativen’, in Sybille Krämer, ed., Performativität und Medialität, (München: Wilhelm Fink, 2004), pp. 13-32

Nyman, Michael, Experimental Music. Cage and Beyond, 2nd edition, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999)

Osborne, Peter, Anywhere or not at all. Philosophy of Contemporary Art, (London/New York: Verso, 2013)

Osborne, Peter, Conceptual Art, (London/New York: Phaidon Press, 2002)

Reckwitz, Andreas, Unscharfe Grenzen. Perspektiven der Kultursoziologie, 2nd edition, (Bielefeld: transcript, 2010)

Saxer, Marion: Article on ‘Composer-Performer’, in Jörn Peter Hiekel and Christian Utz, eds, Lexikon Neue Musik, (Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, 2016), pp. 212-214

Saxer, Marion, article on ‘Medien’, in Jörn Peter Hiekel and Christian Utz, eds, Lexikon Neue Musik, (Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, 2016), pp. 364-368

Walshe, Jennifer, ‘Die Geister der verdeckten Schichten‘, in MusikTexte 159 (2018), pp. 29-38

Walshe, Jennifer: Die Neue Disziplin, in: MusikTexte 149 (2016), pp. 4-5

Wirth, Uwe, ‘Der Performanzbegriff im Spannungsfeld von Illokution, Iteration und Indexikalität‘, in Uwe Wirth, ed., Performanz. Zwischen Sprachphilosophie und Kulturwissenschaften, 6th edition, (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2015), pp. 9-60

Online:

Walshe, Jennifer, The New Discipline, https://www.borealisfestival.no/2016/the-new-discipline-4/ [retrieval date: 16.10.2019].

Walshe, Jennifer, Ghosts of the Hidden Layer, http://milker.org/ghosts-of-the-hidden-layer [retrieval date: 04.03.2020].

Endnotes

[1] Jennifer Walshe, The New Discipline, https://www.borealisfestival.no/2016/the-new-discipline-4/ [retrieval date: 16.10.2019]

[2] See: Michael Nyman, Experimental Music. Cage and Beyond, 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1999, p. 82

[3] As cited in: RoseLee Goldberg, Performance Art. From Futurism to the Present, third, completely reworked and extended ed., New York: Thames & Hudson 2001, p. 126

[4] See Ibid., pp. 126-127

[5] As cited in: RoseLee Goldberg, Ibid., p. 127

[6] See Erika Fischer-Lichte, Grenzgänge und Tauschhandel. Auf dem Weg zu einer performativen Kultur, in: Performanz. Zwischen Sprachphilosophie und Kulturwissenschaften, ed. by Uwe Wirth, 6th ed., Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2015, p. 278

[7] See Ibid., pp. 280-289

[8] Christa Brüstle, Konzert-Szenen, Bewegung, Performance, Medien. Musik zwischen performativer Expansion und medialer Integration 1950-2000, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag 2013 (Beihefte zum Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 73), p. 57

[9] See Peter Osborne, Conceptual Art, London/New York: Phaidon Press 2002, p. 16-18

[10] See Michael Nyman, Experimental Music. Cage and Beyond, 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1999, p. 75

[11] Ibid., p. 80

[12] See Ibid., p. 77

[13] Gabriele Knapstein, Art. Fluxus, in: Begriffslexikon zur zeitgenössischen Kunst, ed. by Hubertus Butin, Köln: Snoeck 2014, p. 90

[14] Michael Nyman, Experimental Music. Cage and Beyond, p. 36

[15] Ken Friedman: Fluxus and Company, in: The Fluxus Reader, ed. by Ken Friedman, Chichester: Academy Editions 1998, p. 251

[16] See Peter Osborne, Conceptual Art, London/New York: Phaidon Press 2002, p. 21

[17] See Gabriele Knapstein, p. 90

[18] Dick Higgins and Hannah Higgins, Intermedia, in: Leonardo 34/1 (2001), p. 49

[19] Ibid, pp. 50-52

[20] Dick Higgins and Hannah Higgins, Intermedia, p. 50

[21] Dick Higgins and Hannah Higgins, Intermedia, p. 53-54

[22] See Jens Schröter, Das ur-intermediale Netzwerk und die (Neu-)Erfindung des Mediums im (digitalen) Modernismus. Ein Versuch, in: Intermedialität Analog/Digital. Theorien – Methoden – Analysen, ed. by Joachim Paech and Jens Schröter, München: Wilhelm Fink 2008, p. 580

[23] See Peter Osborne, Conceptual Art, p. 18

[24] Peter Osborne, Anywhere or not at all. Philosophy of Contemporary Art, London/New York: Verso 2013, p. 99

[25] See Jens Schröter, Das ur-intermediale Netzwerk und die (Neu-)Erfindung des Mediums im (digitalen) Modernismus. Ein Versuch, in: Intermedialität Analog/Digital. Theorien – Methoden – Analysen, ed. by Joachim Paech and Jens Schröter, München: Wilhelm Fink 2008, pp. 591-594

[26] See Andreas Reckwitz, Unscharfe Grenzen. Perspektiven der Kultursoziologie, 2nd ed., Bielefeld: transcript 2010, p. 162-163

[27] See Ibid., p. 172

[28] Ibid., p. 173. [Note: The English translation of the quote is by the author of this paper, who takes full responsibility for any errors]

[29] See Marion Saxer, Art. Medien, in: Lexikon Neue Musik, ed. by Jörn Peter Hiekel and Christian Utz, Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler 2016, p. 367

[30] See Erika Fischer-Lichte, pp. 291-293

[31] See Stefan Drees, Körper, Medien, Musik. Körperdiskurse in der Musik nach 1950, Hofheim: Wolke Verlag 2011, p. 65

[32] Jennifer Walshe, The New Discipline, https://www.borealisfestival.no/2016/the-new-discipline-4/ [retrieval date: 16.10.2019]

[33] Ibid.

[34] See Marion Saxer, Art. Composer-Performer, in: Lexikon Neue Musik, ed. by Jörn Peter Hiekel and Christian Utz, Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler 2016, pp. 212-214

[35] See Jennifer Walshe, Die Neue Disziplin, in: MusikTexte 149 (2016), pp. 4-5

[36] As cited in Marko Ciciliani, Music in the Expanded Field – On Recent Approaches to Interdisciplinary Composition, in: Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik 24, ed. by Michael Rebhahn and Thomas Schäfer, Mainz: Schott Music 2017, p. 24

[37] See Ibid., p. 27

[38] See Karl Katschthaler, From Cage to Walshe: Music as Theatre, in: Music on Stage, ed. by Fiona Jane Schopf, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2015, pp. 126-130

[39] See Franziska Kloos, Jennifer Walshe. Spiel mit Identitäten, Hofheim: Wolke 2017, p. 40

[40] See Ibid., p. 40.

[41] Ibid.

[42] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QkFkDfIdmcU&list=UUUhKlr06M5ZFzZ8kZmPvqNg&index=7 [retrieval date: 25.02.2019]

[43] http://milker.org/thetotalmountain [retrieval date: 20.10.2019]

[44] Ibid., p. 173. [Note: The English translation of the quote is by the author of this paper, who takes full responsibility for any errors]

[45] See Jennifer Walshe, Ghosts of the Hidden Layer, http://milker.org/ghosts-of-the-hidden-layer [retrieval date: 04.03.2020].

[46] Ibid.

[47] See Jens Schröter, Das ur-intermediale Netzwerk und die (Neu-)Erfindung des Mediums im (digitalen) Modernismus. Ein Versuch, in: Intermedialität Analog/Digital. Theorien – Methoden – Analysen, ed. by Joachim Paech and Jens Schröter, München: Wilhelm Fink 2008, p. 580

[48] See Peter Osborne, Conceptual Art, p. 18

[49] See Christa Brüstle, Art. Performance, in: Lexikon Neue Musik, ed. by Jörn Peter Hiekel and Christian Utz, Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler 2016, p. 503-504

[50] Erika Fischer-Lichte, p. 291

[51] Sybille Krämer, Sprache – Stimme – Schrift: Sieben Gedanken über Performativität als Medialität, in: Performanz. Zwischen Sprachphilosophie und Kulturwissenschaften, ed. by Uwe Wirth, 6th ed., Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2015, p. 340

[52] See Jennifer Walshe, Ghosts of the Hidden Layer, http://milker.org/ghosts-of-the-hidden-layer [retrieval date: 04.03.2020].

[53] See Jennifer Walshe, Ibid.

[54] See Uwe Wirth, Der Performanzbegriff im Spannungsfeld von Illokution, Iteration und Indexikalität, in: Performanz. Zwischen Sprachphilosophie und Kulturwissenschaften, ed. by Uwe Wirth, 6th ed., Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2015, p. 39-42

[55] I should like to thank Carina Steger for her help with the English translation and Jeremy Cox for his comments on, and his editing of, this paper.