Contemporary Cello Technique: Performance and Practice

Read as PDF

Table of Contents

DOI: 10.32063/0611

Alfia Nakipbekova

Alfia Nakipbekova is a multifaceted musician: an internationally acclaimed cellist soloist, chamber musician, researcher, interdisciplinary performer/collaborator and pedagogue. A winner of the Outstanding Mastery of the Cello Award at the Casals Competition in Budapest, Alfia has performed in major venues and festivals throughout Europe, USA, Canada, Russia, Australia, the Middle East and Hong Kong and has recorded major chamber music and solo repertoire, including works by Shostakovich, Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Schubert, Martinù, Ravel, Granados, Charles Ives, Rebecca Clarke, J S Bach and Hans Gal, among many others. Her critically acclaimed recordings for Chandos were featured on BBC Radio 3 and BBC 4. Her Martinù album was chosen as the BBC Music Magazine CD of the year, while her Clarke/Ives album was Gramophone Critic’s Choice for 2000.

Alfia studied with Mstislav Rostropovich at the Moscow Conservatoire (BMus and MMus) and received master classes from Daniel Shafran and Jacqueline du Pré. She completed her PhD thesis ‘Performing Contemporary Cello Music: Defining the Interpretative Space’ at the University of Leeds, and is currently researching the subject of musical interpretation from the perspective of Mikhail Bakhtin’s literary theory at Birkbeck, University of London (Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies).

Alfia has given presentations of papers and lecture-recitals at international conferences at the Universities of Hong Kong, Radboud, Birmingham, Goldsmiths London, Bangor, York, Leeds, Paris and Rome. In September 2017, she organised the RMA Xenakis Symposium at the University of Leeds. She is the editor and contributor to Exploring Xenakis: Performance, Practice, Philosophy, published by Vernon Press in March 2019.

by Alfia Nakipbekova

Music & Practice, Volume 6

Resistance and Affordance

Introduction

During the course of the twentieth century, cello technique developed in multiple ways – from the refinement of traditional methods to the introduction of an array of extended and ‘extreme’ techniques demanded by the contemporary and new music repertoire. Since the mid-twentieth century, cellists have been expanding approaches to contemporary techniques through their own performance practice and, based on this, establishing new traditions. Their practical experiences have formed the foundation for a methodology of performing and teaching in the dynamic environment of contemporary cello playing, embracing a variety of strands in the use of non-traditional expressive tools: new music, cross-genre and interdisciplinary performance (theatre, movement), free improvisation and others. In addition, the exploration of sound produced by extended techniques is a prominent part of the currently flourishing movement of performer/composer collaboration. Composer Liza Lim comments on this development:

Because of the non-standardised nature of the sounds I use (often focussed on fluctuating, morphing qualities) and the unusual techniques required to produce them, my work does often necessitate close collaboration with performers. This process of collaboration to explore so-called ‘extended techniques’ has become quite standard practice since the mid-twentieth century.[1]

Although some aspects of contemporary cello techniques have been investigated, many issues deserve further exploration both theoretically and artistically, broadening out from descriptive and systemising approaches towards the performative, philosophical and inter-disciplinary domains of research. Among the elements that need to be considered is the problem of a terminology that could be applied in the complex area of technical styles – from established extended methods to compositional approaches where the cello is a ‘found object’, an ‘assemblage’, a flexible apparatus with ‘movable’ parts and properties,[2] and an objet musical – the concept embodied in Helmut Lachenmann’s Pression (1969).[3] Valerie Welbanks uses the term ‘adapted’ for defining the transitional nature of some techniques that link the distant points within this spectrum:

[W]hen considering extended techniques in the context of a 300-year history, two large categories naturally emerge. Adapted Techniques are those created by modifying traditional techniques, either by expanding their scope or isolating and rearranging their physical parameters. These form a bridge between traditional type of technique playing and Non-traditional Techniques, which involve using an instrument in ‘a manner outside of traditionally established norms’ and depart significantly from traditional cello playing.[4]

This article explores the approaches to contemporary techniques with particular reference to Nomos alpha for solo cello (1966) by Iannis Xenakis. One of the most theoretically analysed works, Nomos alpha embodies abstract and extra-musical concepts involving the performer’s intellectual, physical and imaginative capacities to the full.[5] My practice-led research is centred mainly on my performance experience with Nomos alpha; the process of mastering this composition provoked re-evaluation of the sound and physicality of playing the cello through examining the foundations of the technique in a historical sense, as well as re-conceptualising the technical aspect as an integral part of the interpretative space.[6]

To define some of the particularly challenging modes of playing demanded in Nomos alpha, I have employed the term ‘extreme’ techniques, referring to the combinatorial procedures utilised in the work. Xenakis uses the full gamut of ‘traditional’ extended techniques (glissandi, harmonics, sul ponticello, microtones, battuto bowings, etc.) combining them into tightly-packed complexes and fragmenting the music’s overall texture. The dense score demands an extremely high level of technical agility, concentration and stamina in order to realise their permutations expeditiously in the prescribed tempi.

The article also addresses the relevance and practical use of preparatory studies designed to establish and refine traditional and contemporary techniques, and their interactions and interconnections. Focusing on the contemporary studies from Pro musica nova: Studien zum Spielen neuer Musik: für Violoncello (1985) compiled and edited by Siegfried Palm and Ten Etudes (Preludes) for solo cello (1974) by Sofia Gubaidulina, I will examine the selected studies within the framework of the expressive potential and instrumental approaches to the extended techniques and practice methods for mastering these techniques. The traditional etudes from David Popper’s High School of Cello Playing Op. 73 (1901-1905) will also be discussed in this context.

Traditional and Contemporary Techniques: interactions and interdependencies

The abundance of publications for developing cello technique in the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries reflects the rapidly evolving role of the cello as a solo instrument at the time.[7] Similarly, so-called extended techniques have been developing rapidly since the beginning of the twentieth century as composers have explored new sonorities, textures and various extra-instrumental effects. Traditional studies, together with scale practice, remain a valuable tool for the contemporary cellist for focusing on particular technique(s).[8] In a traditional etude format, the main type of technique often takes the form of the repetition of a particular pattern with some melodic content – the Popper 40 Etudes exemplify this approach. Revisiting the studies while working on the idiosyncratic extended techniques found in Nomos alpha and Liza Lim’s Invisibility (2009), I came to discern subtle links in the physicality of executing left- and right-hand movements within the coherently ‘mapped’ traditional fingerboard. The enlarged palette of sonorities attained through the combinatorial techniques and singular expressive devices such as micro- and quarter-tones, the extensive array of glissandi, extreme ranges of dynamics and registers, the circular bow etc. remains ‘rooted’ in the ground of the repertoire of physical responses that has been accumulated through the global development of the cello.

The traditional system of establishing and refining technical mastery in Popper’s method aims to induce a high degree of precision in the left-hand position changes, co-ordination and, importantly, instrumental stamina; the variety of tonal colours attained through the technical stability and clarity of articulation are still relevant to much of the contemporary and new music repertoire. Adriana Venturini considers the significance of Popper’s contribution as a crystallisation of the principles of cello technique for twentieth-century cellists:

Since the publication of Popper’s Hohe Schule des Violoncello-Spiels, the frequency of publication of etudes dropped significantly. […] Popper was one of the greatest cellists of the nineteenth century and through his etudes, he lives on today in every virtuosic cellist’s muscle memory.[9]

By focussing on this aspect of muscle memory, rather than upon the actual musical patterns employed, the ‘old’ studies can be used as reinforcing exercises in the context of extended and extreme techniques. This may occur in a variety of ways. For example, some of the etudes are designed for developing security in a particular technique; Popper’s Etudes Nos. 12 and 33 are a case in point. By utilising the ‘waving’ patterns which they employ in the in the left hand and the bow, an evenness of semiquavers in the left hand can be achieved. This is done by combining stability of the bow in string crossing (attained by focusing on legatissimo motion) and the minimal adjustments of the bow angle with elasticity in the left hand in position changes supported by clearly articulated thumb positions. Cultivating the awareness of these two planes – horizontal (in the bow arm) and vertical (in the left hand) – integrates the physical motions and develops an instinctive adaptability to the playing ‘zone’.

The practice process can be reinforced by adding layers of complexity to the studies: for example, by experimenting with chromatic transpositions to different keys, similar to the method employed by jazz instrumentalists[10] or by lengthening the slurred phrasing over two bars or more (Etudes Nos. 2, 3, 9, 10, 12 etc.) so as to refine bow distribution in extremely slow motion. Regarding the instrumental stamina that the method helps to develop, Charlotte Lehnhoff makes the following general observation:

[T]here is simply no let-up in the etudes. This quality, of not stopping, is doubly reinforced by the absence of contrasting or different thematic material. Not being able to stop, along with the absence of contrast, provides yet another very important contribution to the development of virtuosity, namely, building up the stamina needed to play through an entire work.[11]

The popular encore piece Dance of the Elves is another example of the ‘Popper’s patterns’ method that can be used for developing these qualities. The piece provides training material that is organised into clear blocks of symmetrical patterns moving rhythmically upwards and downwards. The technical skills it encourages include:

- Coordination between the bow and left hand;

- Spiccato bowing;

- Developing stamina, which is essential for sustaining an evenness and consistency in spiccato, combined with accuracy of intonation in high positions.

For developing the stamina needed for a high quality spiccato in a consistent tempo, the Soviet virtuoso cellist and pedagogue Daniel Shafran recommended projecting one’s practice beyond the required parameters, e.g. playing the piece twice (which will naturally increase the tempo) as if it was a single piece – contracting the perception of the speed and duration.[12] Played in a faster tempo, the spiccato bowings will be modified into the sautillé mode of a bouncing bow motion. As outlined by Vladimir Grigoriev, sautillé emerges from the accelerating détaché stroke; when decreasing the bow’s weight on the string is combined with using a smaller amount of the bow, regular oscillations of the string occur.[13] The ‘shimmering’ quality of the spiccato/sautillé stroke is determined by the fine balance between the density and lightness in the interactions of the bow’s hair with the string, and between the natural elasticity of the bow stick and a controlling motion of the right arm; in addition, it is necessary to avoid any tension in the shoulder for sustaining the delicate state of ‘stillness in motion’.[14]

Performing Nomos alpha is an intense and strenuous act that involves totality of the performer’s senses, physical (muscular) strength and meta-fast responsiveness; precision of the pitches in rhythmical patterns and their kaleidoscopic transitions can be approached from the base of traditional technique outlined above. Discussing one of the most radical compositions for solo cello by Helmut Lachenmann Pression, Liza Lim comments:

One of the interesting things that comes out from the extensive literature around this piece is the realisation that the gestures, for all their radicalism, still point to the classical performance; the performer is still drawing the bow over the instrument, and even if that movement or lifting the bow creates a noise […] it still has this relation to traditional past.[15]

One of the practical questions related to learning Nomos alpha is the work’s seeming incompatibility with traditional repertoire: the ‘unnatural’ techniques, the physical condition and intellectual effort required during the process of practising and performing. At the beginning of my experience with the piece I had to isolate my practice of Nomos alpha from all other repertoire; later on, as the time passed and my learning process evolved, deepened and became informed by the experience of several live performances in various conditions, I was able to incorporate this new knowledge of the cello into my daily practice. For example, I was able to juxtapose Robert Schumann’s Concerto op. 129 (1850) with Nomos alpha, practising short sections from each piece in turn. With time, working on various styles of music alongside Nomos alpha felt invigorating for the hands and seemed more natural than playing the piece exclusively for extended periods.

In a process such as this, the daily exposure to diverse and ‘incompatible’ techniques functions as a catalyst for effectuating new ideas and creating unexpected possibilities. Clarinettist Lori Freedman re-affirms this point from his own experience of performing Xenakis’ music:

Certainly for the performer this music insists on a state of absolute presence unprecedented in the repertoire. Perhaps it is this quality, one of such fundamental focus that singularly forces me back to the basics of clarinet playing.[16]

Indeed, working on Nomos alpha has given me a fresh stimulus for investigating the ‘reverse’ connection between the domains of traditional and contemporary techniques – how working on the extreme techniques is re-structuring my instrumental reflexes and my global perception of the playing process. Through the continuous search for the appropriate technical methods and psychological readjustments, the problem of a particular physicality associated with the piece – its ‘brutal’ approach towards the instrument (manifested in some percussive techniques and recurrences of abrupt de/re-tuning C string that ‘upset’ the cello) – can be resolved through individual practical experience; the intimate knowledge of this process can only be accumulated and passed on, to some extent, by the cellist who is fully committed to the arduous path towards mastering Nomos alpha. At times, I question the problem of inexorable physical ‘violence’ towards the instrument involved in playing the piece; such questioning leads me to search for the most appropriate level of intensity in the interplay of opposing forces: Ferocity/Refinement, Sound/Noise and Precision/Chance.

Xenakis’ writing for cello reveals the authentic depths of the instrument’s technical range; at the same time, it shows the composer’s commitment to expand this range by refining and intensifying every facet of cello playing. The resultant satisfying confluence of the sensual and intellectual – listening through the entire body and understanding with the fingers – can be experienced by the individual performer and incorporated into a new instrumental tradition. The dynamics of the hands moving across the fingerboard generating the shapes, movement and transitory structures, might be perceived as an embodiment of the principle of technique as architecture. Perhaps, Xenakis’ intuitive grasp of the scope of intensity and expression in the domain of the cello is subliminally linked to his architectural thinking and creative practice.

Video clip 1 Xenakis, Excerpt from Nomos alpha (vimeo), performed by Alfia Nakipbekova

Practice Methods: direct and indirect approaches

My own experience in grappling with these issues has brought to the fore a multitude of questions regarding practising generally and, more specifically, in the context of preparing meta-complex works. In Nomos alpha I would single out two elements that demand a re-evaluation of learning and practice approaches. These are: 1. individual units (events) assembled by combinatorial techniques; 2. transitions between these micro-structures. As pointed out above, the combinatoriality of techniques within the units and their progression is complicated by the ‘unrealisable’ (utopian) tempi.[17]

Muscle memory relies on repeated physical gestures and their patterns; one of the elements in learning the piece is delineating the patterns within the work’s pulse to clarify and organise (intellectually and instrumentally) the multiplicity of transitional spaces. Practising in groups of gestures is one of the methods for building the level of one’s reliable instrumental ‘athleticism’.[18]

To give an example, in bars 80-94 of Nomos alpha, there are three distinct gestural groups. The first two are characterised by their clear direction: in the first, this consists of a downward movement, pizzicato, with upward mini-slides (in fast tempo, these ‘ornaments’ are executed by vibrato-like stresses on each double stopping); in the second, this pattern of downward motion is repeated, but with figuration that provides a momentary sense of stability before the scintillated cluster of glissandi sul ponticello in the third group, whose overall direction is slightly upwards. For the performer, another factor distinguishing the first two groups from the third is that they are played in thumb position (artificial harmonics), which gives a sense of continuity in the left hand; the following group is played with the third finger moving rapidly within the area of the fourth interval (G to C) on the D string. In this latter sequence the reference points are the two instances of dynamic marking fff where the focus is transferred to the momentary increase in bow pressure.[19]

Non-traditional techniques such as these can be mastered through working directly on the compositions, without any preparatory stage of learning through contemporary studies. However, some introductory exercises could be useful for focusing on techniques that might be new to the cellist, e.g. a variety of glissandi, harmonics and tremolandi, fast ‘leaps’ into the high positions, fine bow control in variations of sul ponticello and sul tasto, and other expressive devices. The preliminary direct (‘technical’) work will be enlivened and deepened by an indirect approach (at an appropriate stage, as a part of an evolving interpretation) that I have termed Associative Method. With this term, I aim to define a way of internalising a composition (encompassing a totality of intellectual and physical capacities of the performer) through the intuitive links and subjective associations with various arts genres, philosophy, nature, etc. – the domains of imagination and thought – that resonate with the performer’s artistic temperament.[20] The cellist might choose to work on preparatory technical material as part of his/her direct approach. The two distinct examples of the ‘traditional contemporary’ studies designed for the cellists wishing to study extended techniques and those in a contemporary idiom – Pro musica nova: Studien zum spielen neuer Musik für Violoncello edited by Siegfried Palm and Ten Etudes by Sofia Gubaidulina – are valuable contributions to the corpus of cello methods.

Contemporary Studies: Palm and Gubaidulina

As an active soloist and educator, Palm followed David Popper’s example in providing cellists with a compendium of the latest technical methods and expression. As in Popper’s case, Palm’s 12 Studies reflect his own virtuosity and understanding of the instrument’s expressive potential. He conceived the idea of creating a set of etudes to help the new generation of cellists to master techniques that are required for the new repertoire of the second half of the twentieth century. All the pieces were written by composers invited by Palm, ‘who have sought to build a bridge between the inexperience with contemporary instrumental techniques and the demands made by contemporary composers in their works’.[21] Stressing the current need for establishing the pedagogical practice of teaching non-traditional techniques, Palm asserts that:

The students of today can find enough etude collections to help them learn the masterpieces of the past […] However, we do not have a compendium of etudes for the music of our own day which would help us overcome the difficulties which appear to many of us as insurmountable’.[22]

For each piece, Palm offers a commentary on what are, for him, the key expressive and technical issues, giving us an insight into his approaches to practice and performance.

Below are my own brief comments on the types of extended techniques that are covered in the studies and their characteristics (Table 1):

| 1. Günther Becker (1968)

Studie zu „Aphierosis“ |

The main focus is on bow technique – variations in articulations: percussive effect (col legno), sul ponticello, staccato, tremolando and playing between the bridge and the tailpiece. |

| 2. Hans Ulrich Engelmann op. 38 (1970)

minimusic to Siegfried Palm |

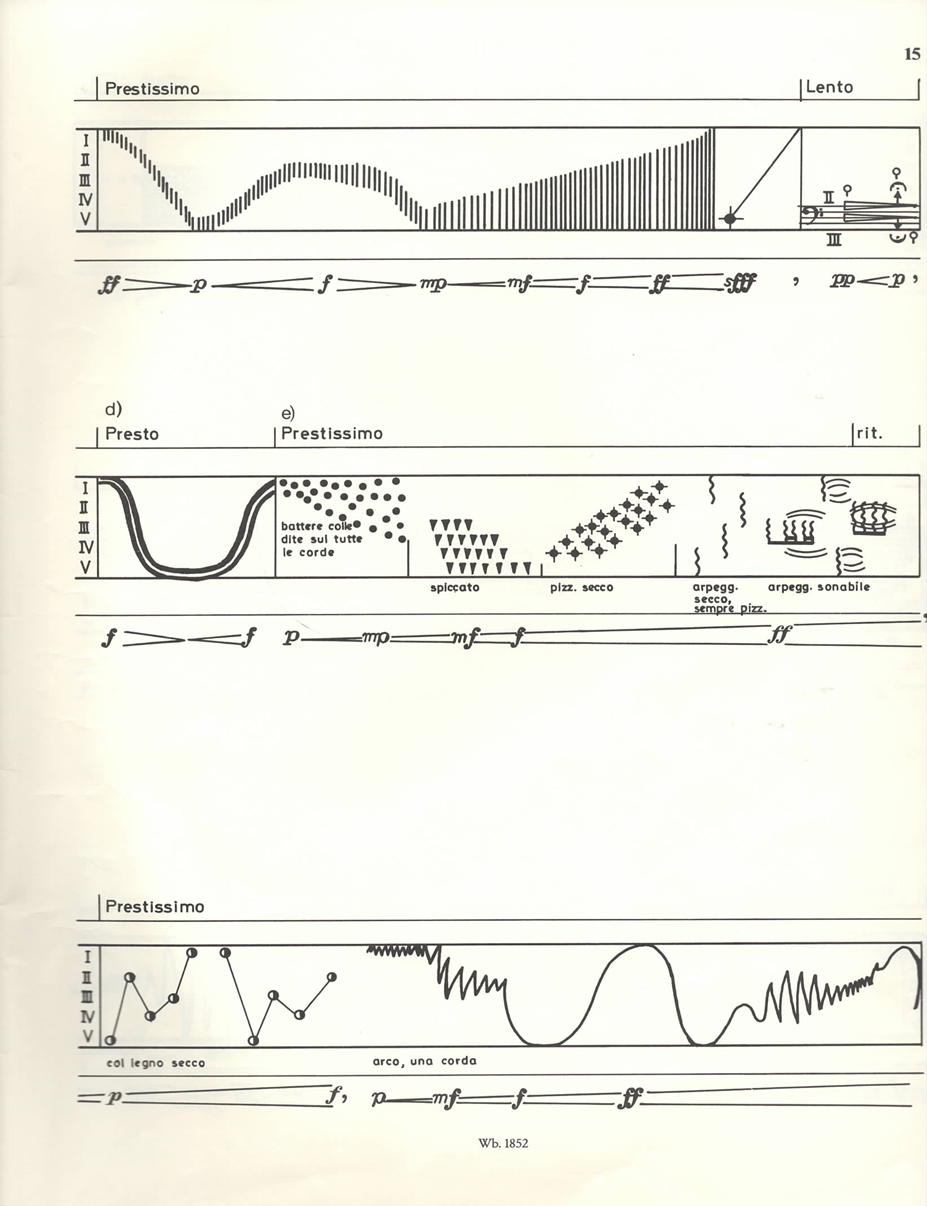

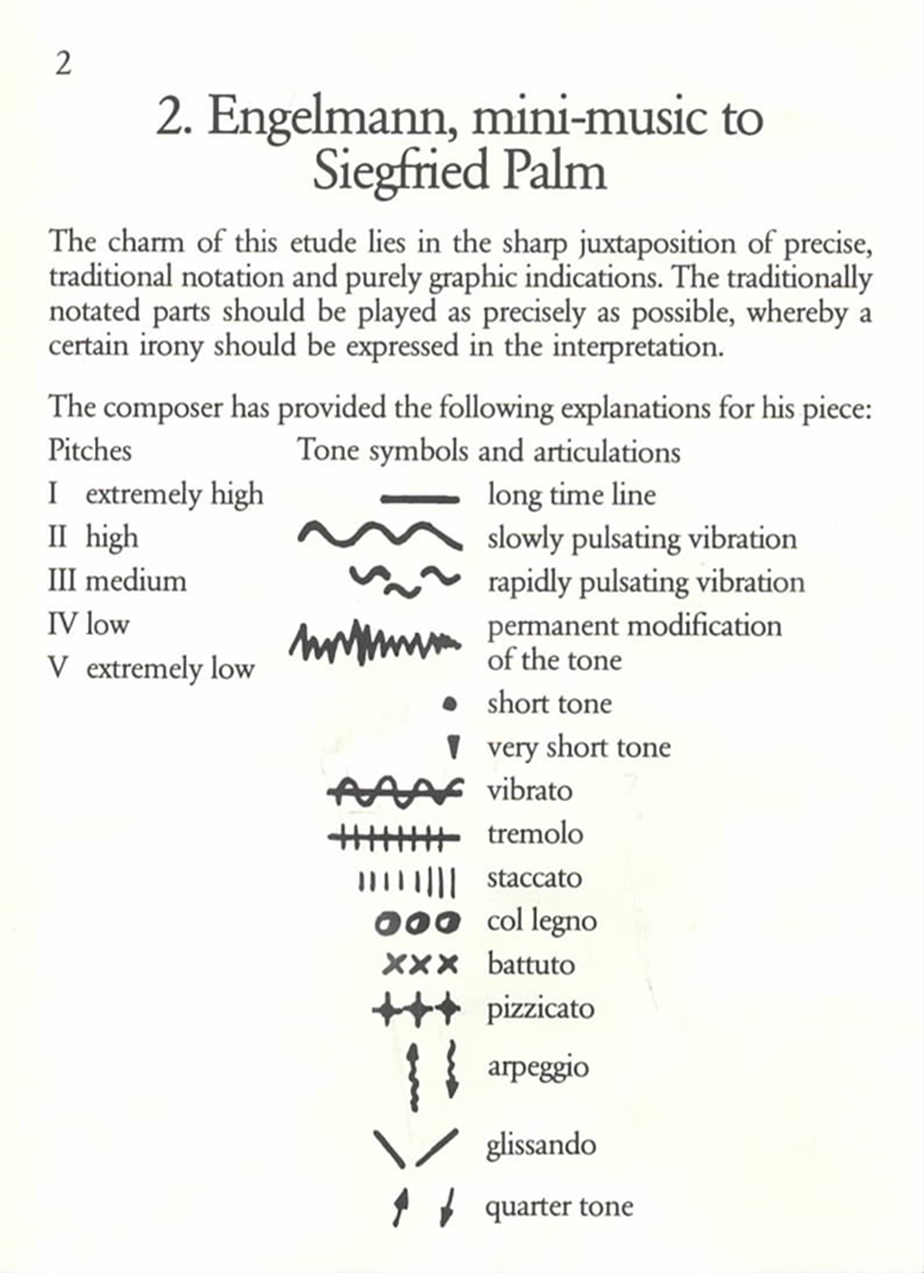

This etude might be used as an introduction to graphic notation (Example 2 and Figure 1), containing one example of aleatoric procedures and experimenting with imaginative application of the array of extended techniques. |

| 3. Wolfgang Fortner

Studie zu „Zyklus“ |

Useful for practising wide intervals combining artificial harmonics and stopped pitches. |

| 4. Michael Gielen (1969)

Passagen aus „die glocken sind auf falscher spur“ |

This short piece requires subtlety in expression, exploring changes in dynamic range, for example, in bar 3, where fff recedes to p during a downward glissando in double stops. It is also a study in rubato – for developing a sense of timing, tonal colours and fluid transitions between the short sections. |

| 5. Mauricio Kagel (1971)

SIEGFRIEDP’ |

Palm considers this piece to be the most difficult in the set, asserting that ‘the composer has included practically every problem which is encountered in the performance of new music.’[23] Among the difficulties presented by the piece are: accurate reading of the score – variations of the row comprising the five pitches (the letters of Palm’s first name), and the issue of a fast tempo necessitating playing from memory. The vocal part requires precision in pitch – this is an additional challenge for many cellists. |

| 6. Milko Kelemen (1969)

Vorstudie zu „Changeant‟ |

To fully benefit from this study, it is important to appreciate the original composition Changeant by Kelemen (b. 1924), who, as noted by the critic, Everett Helm (in 1965), ‘represents the most “radical” trends of younger Yugoslav composers’.[24] Listening to the composition reveals the scope of sonorities in the preparatory study: glissandi combined with trills and ‘floating’ pitches, as well as instances of tonal distortions. |

| 7. Konrad Lechner (1971)

Drei kleine Stüke |

Notable techniques include scordatura (detuning C to B), indefinitely high pitches, striking the strings with the left palm, and battuto bowings moving in opposite direction with glissandi (II, ‘Schnell’, bars 1 and 12). |

| 8. Nikos Mamangakis (1969)

Askisis |

The study develops a sense of timing in rubato and intensity of expression, refining the gradations in vibrato (from non-vibrato to lento vibrato), a variety of chords (pizzicato and arco), double stops, and contrasts between the fast pizzicato sections and longer undulating lines played arco libero, sempre legato. |

| 9. Krzysztof Penderecki (1967/72)

Cadenza aus dem Konzert für Violoncello und Orchester |

Palm considered the inclusion of an excerpt from the Cadenza for Penderecki Cello Concerto No.1 to be beneficial for students learning techniques and expression in the new music of his time. The techniques, which include overpressure (‘hard, tonally distorted, noisy accents’), playing between tailpiece and bridge, knocking on the side of the instrument etc., are not challenging in themselves. The benefit of this piece however, is in using these effects for expanding expressive range, aiming for a broad projection in sound and gestures of playing a concerto. In this context, the articulation and expressive qualities of these techniques differ from those of the other studies. |

| 10. Jacques Wildberger (1969)

Studie |

This piece is marked by a focus on transitions – in: 1. the bow (at the opening the tremolo is indicated as an unbroken transition from the pp at the tip of the bow moving downwards towards the bridge crescendo and returning to the preceding tone); 2. the left-hand (the passage with the pitches and direction indicated by the graph transiting without a break to the notated sequence and returning to the graph). Another feature in this study is percussive noise produced by tapping the left fingers on the table and the side of the cello as well as on the indicated pitches on the fingerboard. |

| 11. IsangYun (1970)

Studie aus „Glissées‟ |

This work is a companion piece for the longer score Glissées (1970) by Korean composer Isang Yun, who employed a traditional Korean music idiom in writing for cello through his use of glissando. Palm provides some instructions regarding the execution of glissandi and the way of working on the ‘technical’ difficulties before ‘adding’ the dynamics. However, in my view, the totality of expression must be practised simultaneously so as to establish technical and mental clarity in terms of the musical direction and connective ‘tissue’ of the piece. The work is also notable for its use of individual dynamic markings for each string in the double stoppings – this singular device had already been investigated and honed by Xenakis in Nomos alpha in 1965. |

| 12. Bernd Alois Zimmermann

Vier kurze Studien |

The four contrasting pieces provide useful practising material for the refinement of a particular technique in each study. The first piece requires coordination between the two contrasting bow strokes in an irregular sequence, in the second one, the variety of pizzicati (right- and left- hand, sul tasto, and combined with harmonics) gives an opportunity to understand the pizzicato techniques, which are generally not sufficiently covered in studies as distinct technical skills; the third etude develops coordination and alertness in changing from heavy spiccato at the frog to the tied notes and left-hand pizzicato; the final piece is remarkable in its concept of aligning the ‘geography’ of the fingerboard with timing – as described in the annotations: ‘The duration of each note is determined by the distance between the notes.’ |

Table 1 Siegfried Palm, 12 Contemporary Studies

To give an indication of the kind of scores contained in the collection, and the ways in which Palm’s comments seek to guide the cellist through both the notational and performative challenges, I shall offer an example drawn from the second of the pieces, Engelmann’s mini-music to Siegfried Palm. In the example and figure below (Example 1 and Figure 1), first, there is a reproduction of a section of Engelmann’s score; then Palm’s commentary on the whole work is provided; finally, I have included a sound clip of my own performance of the section of the piece corresponding to the score extract:

Example 1 An example of graphic notation from Engelmann, mini-music to Siegfried Palm © 1971 by Musikverlag Hans Gerig, Köln © 1980 assigned to Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden

Figure 1 Palm, Instructions for mini-music to Siegfried Palm© 1971 by Musikverlag Hans Gerig, Köln © 1980 assigned to Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden

Sound clip 1 excerpt from Engelmann’s mini music to Siegfried Palm. Performed by Alfia Nakipbekova

Sofia Gubaidulina’s Ten Preludes (originally titled Ten Etudes) for solo cello is another outstanding example of a contemporary set of studies that can be productively included both in teaching material and as part of a concert repertoire. The composer describes them as ‘sketches’ for her future compositions and as part of her own study of the cello’s expressive possibilities.[25] Paradoxically, the set is also one of the most effective for introducing the elements of non-traditional technical skills – as confirmed by my own pedagogical experience.

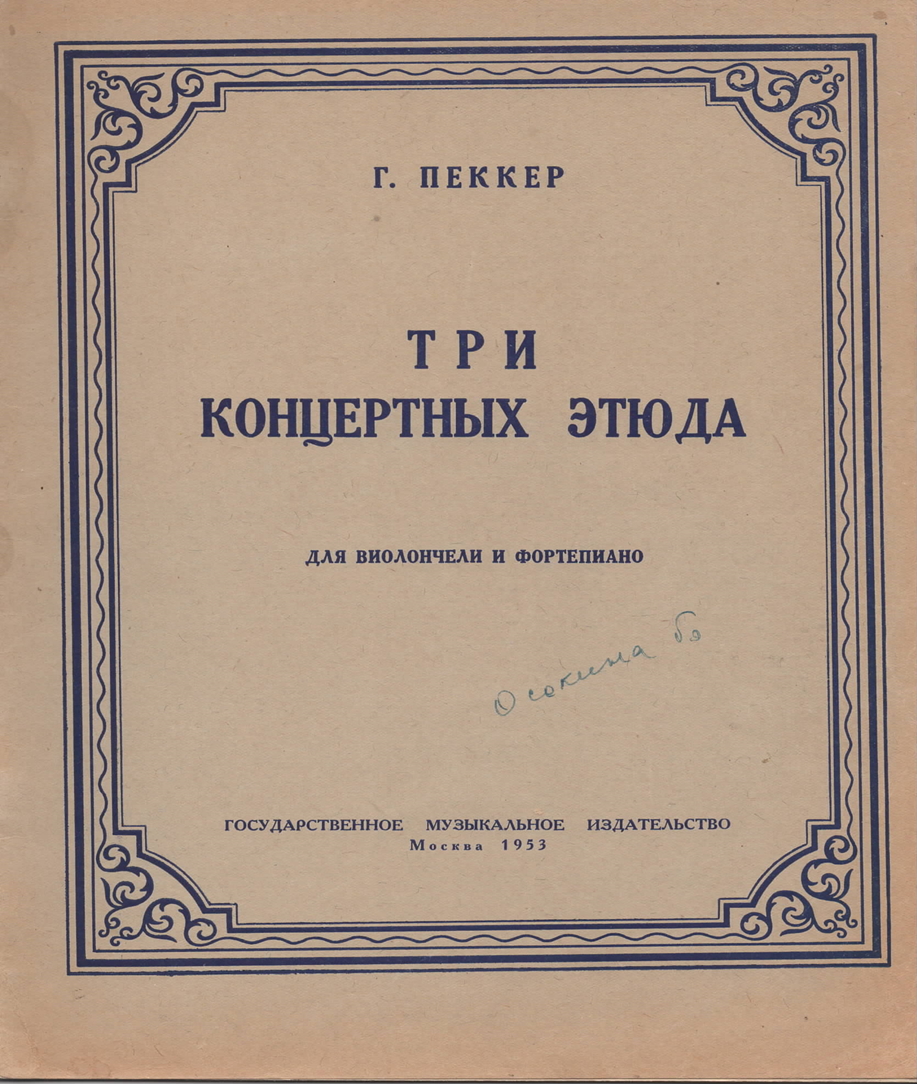

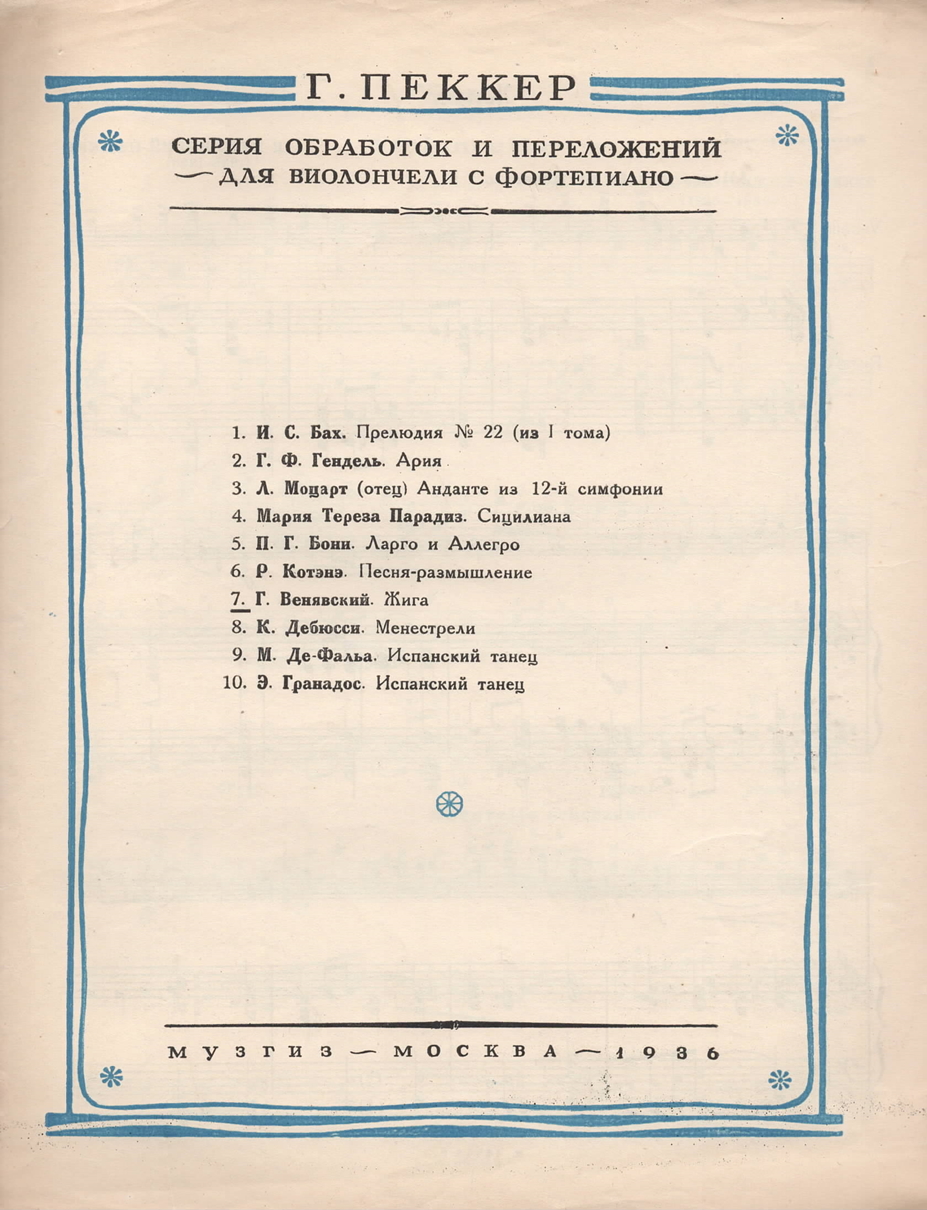

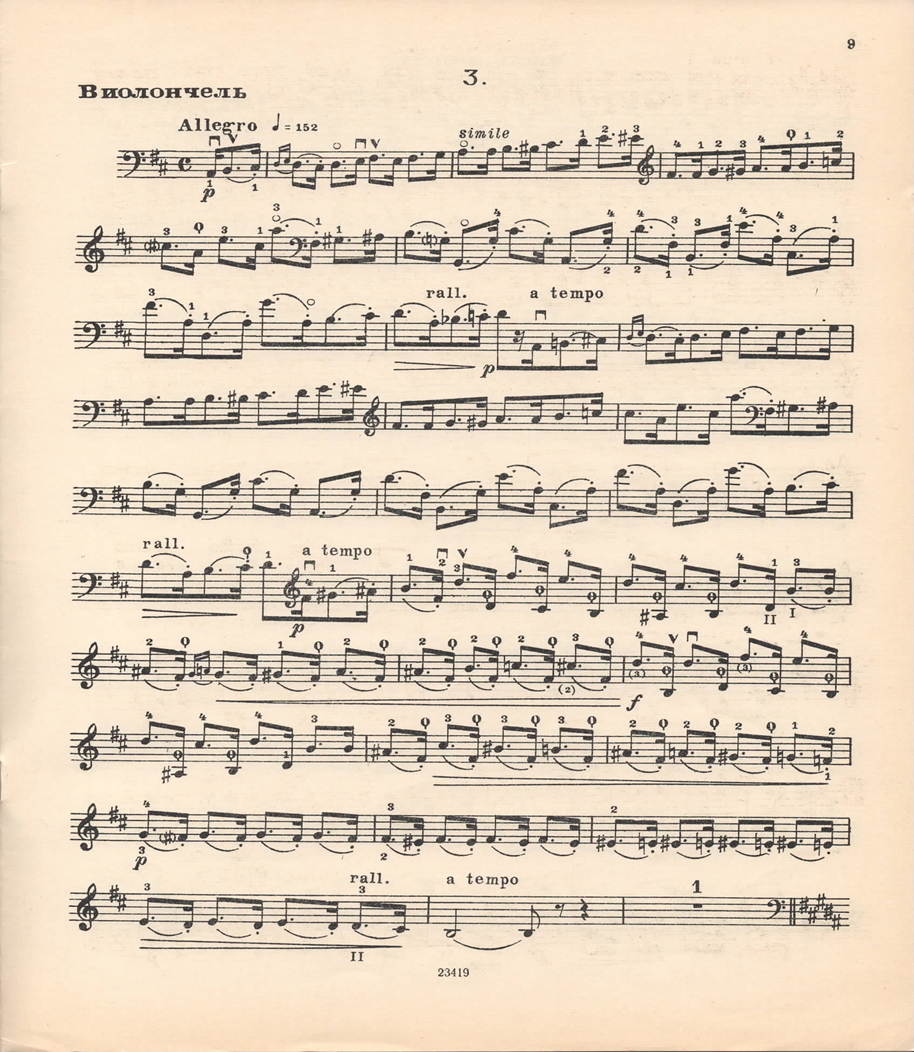

The Ten Etudes were commissioned by the Russian cellist Grigory Pekker (1905-1983) in the early 1970s, as he was looking for new study material for his students at the Novosibirsk Conservatoire. Born in Kazakhstan, Pekker studied at the Petrograd Conservatoire and later in the Leipzig Conservatoire with Julius Klengel (1927-1929). Pekker is known as the first performer, in December 1923, of the Trio Op. 8 by Dmitri Shostakovich (with violinist V. Shor and the composer himself who, at the time, was also a student at the Petrograd Conservatoire)[26]. As a composer and arranger, Pekker made a substantial contribution to the pedagogical and concert repertoire for the cello. His works include Three Concert Etudes for cello and piano (published in 1953, Figure 2) and various arrangements of popular pieces for cello and piano (published in 1936, Figure 3). He also edited Popper’s Studies Op.73 (in an edition published in 1983), the cello part of the Antonin Dvořák’s Cello Concerto Op. 104 (published in 1977), and other works.[27]

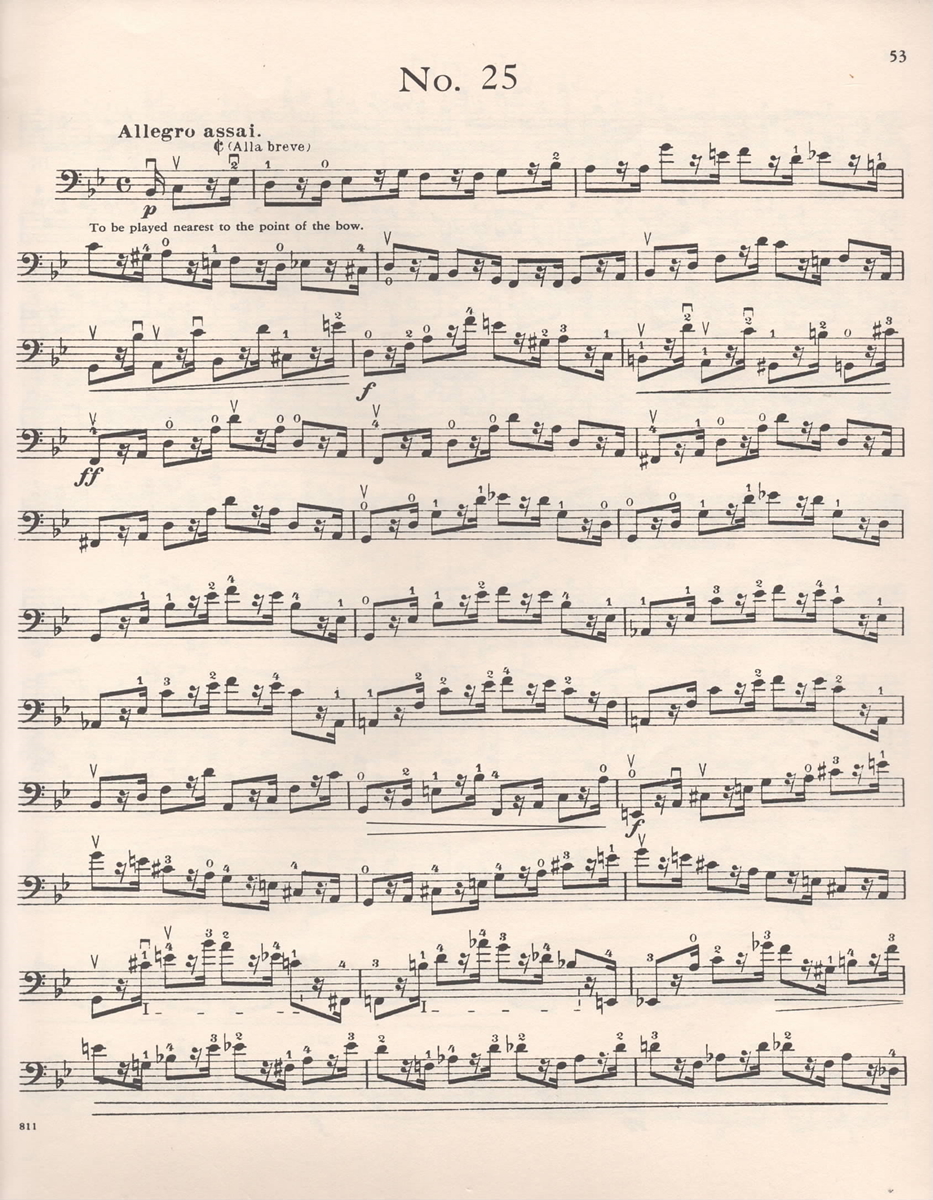

In their compositional style and approach to technique, Pekker’s Etudes show the influence of Popper’s traditional method, as illustrated by the following two examples, the first from Pekker’s Etude No. 3 and the second from the Etude No. 25 by Popper (Examples 2 and 3):

According to Michael Kurtz, Pekker approached several composers, including Sofia Gubaidulina, with the idea of creating a compilation of studies for his cello students. He received the Ten Etudes from her in 1974. However, ‘because Pekker had never studied contemporary music, he did not know what to do with the score he had been sent and simply ignored it’.[28] The composer clarifies her intention:

The story is that he wanted the etudes for cello to be for specifically pedagogical purposes. But for this purpose, the etudes don’t work. They are my fantasy rather than etudes examining a pedagogical aspect.[29]

As in the case of Popper’s studies, Gubaidulina’s Ten Etudes are concise and simply structured; additionally, the title of each etude indicates the primary techniques featured – this renders them easily understood by the students who might be new to contemporary styles. In that sense, the set ‘fulfills these traditional expectations by exploring contemporary cello techniques […], the way a David Popper etude might explore a fingering pattern in thumb position’.[30] At the same time, the pedagogical usefulness ‘is simply a byproduct of their primary function as a playground for Gubaidulina, in experimenting with larger compositional ideas’.[31] This fine balance between practicality in pedagogical practice and the highly successful compositional experimentation makes the cycle unique.

The simplicity of the Etudes’ titles seems to indicate their purely didactic nature:

I. Staccato, legato

II. Legato, staccato

III. Con sordino, senza sordino

IV. Ricochet

V. Sul ponticello, ordinario, sul tasto

VI. Flagioletti

VII. Al Taco, da punta d’arco

VIII. Arco, pizzicato

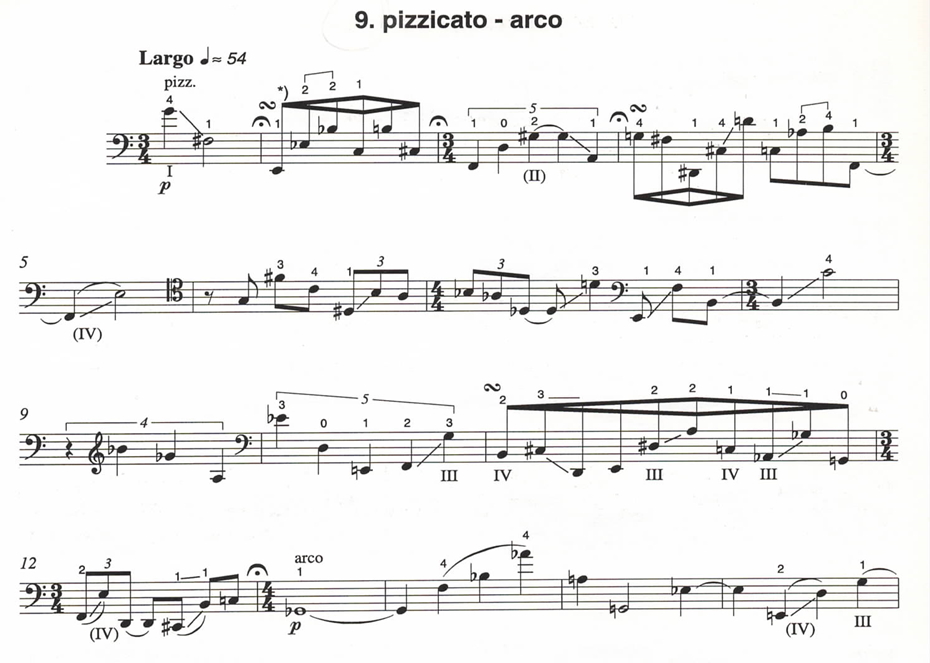

IX. Pizzicato, arco

X. Senza arco, senza pizzicato

However, I consider this set of short pieces to be one of the most effective examples of a volume of contemporary studies that transcends a purely pedagogical application, integrating ‘technique’ and ‘musical content’. Gubaidulina makes an important comment regarding her perspective on the ‘techniques’ she employs:

I examined these etudes as not only a sampling of various types of sounds [on the cello] but the idea of a two-part form fascinated me. Say, from one type of transition to another. This really interested me. For example, at the beginning, playing the bow at the frog and then eventually coming to the tip of the bow; this creates a two-part form.[32]

From this statement, the two factors may be drawn that are significant when practising and performing the cycle:

- The technical features are central to the structure of each piece

- The focus on transitions adds an idiosyncratic dimension to the technical fluency called for in each study.

Biber elucidates the structural concept of the etudes:

While two-part forms are common in music, their structure is less often dictated by timbre or articulation. Such musical elements are typically considered surface material rather than structural. Gubaidulina regards these elements as equally important to elements of harmony, rhythm, and texture.[33]

This concept finds echoes in several of the major works that employ extended techniques. For example, in Nomos alpha the textures produced by the extended techniques, mould the structure of the piece:

Since there can be no elaboration of thematic, melodic or harmonic development, colour and texture occupy the stage. Particular modes of playing such as pizzicato, col legno, battuto, sul ponticello with tremolo, harmonics and so on, traditionally of secondary importance take on a primary function – not textural filling but as geological features forming the crust of this landscape.[34]

Similarly, Tanja Orning in her study of Lachenmann’s Pression notes that:

[I]n Lachenmann’s music these sounds do not appear merely as extra-musical sounds or extended techniques but have become the very structural foundations of his composition.’[35]

Extending this interpretation of the interactions between the articulation and structure, we can rethink one of the fundamental bow techniques, legato, as a structural tool. Grigoriev points to the inner liveness of the legato sound where ‘each tone is living independently in various degrees’ while, at the same time, flowing into the next sound shaping the global arch of the piece in the process of performance:

In Fritz Kreisler’s view, any legato bow stroke contains within it a hidden portato, that is realised through the impulse in vibrato for articulating the beginning of each sound, micro-glissando in the finger, supple, slightly uneven bow motion (and even employing vibrato in the bow). […] David Oistrakh asserted that legato must retain a conspicuous impulse in the bow […] this will result in a powerful, expansive sound […] and ‘breathing quality in phrasing’.[36]

Sound clip 2 ‘The inner liveness of the legato’. D. Popper Etude No. 29. Performed by Alfia Nakipbekova

Transitions and ‘stuttering’

One of the significant benefits I feel I have obtained through working consistently on Nomos alpha is a considerably enhanced awareness and practical knowledge of performing transitions. In the arduous process of preparing the piece for performance, I recognised the exigency of focusing on the ‘liminal’ spaces located within the textures and events, the micro- and macro-pauses (moments of silence) that have a multitude of functions, expressive properties and technical complexities; this focus becomes intensified on a granular level – in the rapid transitions between the pitches within events.[37] In Matossian’s analysis, the events’ durations vary between 1 to 30 seconds, with an average of 5.3 seconds.[38] Discussing the extraordinary technical difficulties presented to performers, who, at times, feel that they cannot reproduce scores precisely as written, meaning that the performances have to be an approximation, Xenakis states:

My works are to be performed according to the score, in the required tempo, in an accurate manner. […] I do take into account the physical limitations of performers […] but I also take into account the fact that what is limitation today may not be so tomorrow. […] The artist can live during a performance in an absolute way. He can be forceful and subtle, very complex or very simple, he can use his brain to translate an instant into sound but he can encompass the whole thing with it also.[39]

The state of ‘living during a performance in an absolute way’, with each moment simultaneously encompassing the global structure, can be assisted in its realisation through a focus on, and awareness of, the transformational intersections in textures and silences. With this in mind, and in order to offer a concrete example, when approaching Gubaidulina’s Etude/Prelude No. 9 through a focus on its transitions, I find that I experience it as a ‘living’ entity with a contracting/expanding body formed by the moving elastic ‘threads’ (glissandi) within its inner core (Example 4).

Example 4 Gubaidulina Prelude No. 9, pizzicato – arco, bb. 1-16. By kind permission of © 1977 MUSIKVERLAG HANS SIKORSKI, Hamburg

Visually, these inner permutations are traced as the lines in the score indicating glissandi. In performance, the micro- and macro transitions are embodied by particular physical gestures required for connecting the pitches on the fingerboard; the physicality of the sliding motions is an expressive component of the piece. Michel Berry argues for the significance of the physical gestures in Gubaidulina’s compositions in terms that resonate with my intuitive understanding:

Sofia Gubaidulina is one of many composers whose music features an increased attention to the body. Some of her works require spatial separation of performing forces; others require interaction between live music and recorded sound. Both techniques rely on the audience’s visual inspection of the performance arena. In some instances, I would argue that practical bodily gestures – those movements of the body that are concerned with producing sound from one’s instrument – are actually more important to the work than the resulting sounds.[40]

Thinking of gesture as a component of theatrical performance,, it is perhaps significant that Gubaidulina’s approach to the various ‘techniques’ extends to her perception of them as ‘characters’ in a play:

These miniatures, which evoke polar opposites in the sphere of sound production on a string instrument, are little scenes in which the heroes are: 1) certain aspects of string instrumentation, 2) methods of sound production, and 3) various bowings… In almost all of the pieces the opposites interact in pairs.[41]

Awareness of context, of subjective associations and of the imagery evoked by the composer’s comments deflects the intensity of focus away from being based solely on the technical details of playing and, instead, channels it into animating the gestures. Cellist Didi Chang-Park characterises the liberating nature of his experiencing the quality of ‘liveness’ in performing Lachenmann’s Pression and Sept Papillions (2000) for solo cello by Kaija Saariaho as a form of ‘stuttering’ (after Craig Dworkin’s Stutter of Form):

Sept Papillons is not at all self-consciously and radically experimental or performative. Yet in the piece, I intuited a stutter. I found in Sept Papillons a certain kind of stuttering, more subtle and more persistent than that of Pression, a stuttering that led me closer to a new way of being with my body and the instrument, and with sound.[42]

By construing the instrumental ‘techniques’ as gestures, the performer enlarges the performative space, centring it on his/her corporeal presence such that, in Orning’s definition, ‘the body of a musician becomes an inseparable part of the music in the moment of performance, through physical and indeed almost choreographed work.’[43]

Conclusion: total technique

We might think of new techniques as occupying a special area that needs a separate method of learning, arranged progressively from simple to difficult, or framed as a set of special rules and approaches for each physical movement (correlated with the particular technical device with which it is associated). However, extended techniques can be mastered from the base in conjunction with traditional techniques, as well as within the context of each piece that requires them; any short contemporary piece can be used as a ‘study’ for exploring a particular technique or expression.

The ‘new’ virtuosity, with its own diverse historical background and traditions, is in the process of dynamic expansion and development. The prominent performers in this field (Siegfried Palm, Rohan de Saram, Frances-Marie Uitti, Christopher Roy and many others) and the performance traditions established or still evolving through compositions such as Lim’s Invisibility, Saariaho’s Sept Papillions, Xenakis’ Kottos and Nomos alpha and Lachenmann’s Pression, are all part of this new rich tradition. To express these works’ visceral virtuosity and expressive depths, innovative ways of practising must be researched that integrate into a single extended ‘method’ traditional cello repertoire and individual experiences in the domain of contemporary music. The idea of using a focus upon transitions within the pieces as a practical tool that is potentially applicable to the global body of the cello repertoire, spanning three centuries of development of the cello, might be considered as a principle of a highly developed total technique. As confirmed by my own experiences, the ‘cross-pollinating’ of the various technical schools, methods and artistic directions refined by generations of cellists, brings to fruition a new quality in one’s physical relationship with the instrument and an openness in attitudes and ways of performing, listening and communicating.

In attempting to define the contemporary cellists’ technical prowess, terms such as ‘new’, ‘transcendental’ (Arne Deforce) and ‘mycelial’ virtuosity (Nakipbekova), among others, have been used. They share the aim of improving upon the term ‘extended techniques’, which does not fully convey the complexity of a phenomenon that demands a distinct quality of new expression and sound. Perhaps a term such as expressive modes, in that it pertains to the amalgamated domain of conceptual and instrumental elements, might give a fuller definition of the contemporary cello’s expressive range.

Another aspect of this kind of virtuosity relates to the cellist’s ability to read and ‘adapt’ to complex scores – a skill which can only be acquired through numerous experiences of working with and performing contemporary compositions that are notated in a variety of styles. This particular skill is extensively developed by those performers who specialise in this area of music; however, I consider the techniques of fluent reading of non-traditionally notated scores to be part of a general instrumental training.

In performing new music, contemporary cellists participate in co-creating a composition. This may either take place directly, when the performer works with the composer and makes a substantial input into the composition by experimenting with sound, or it may occur indirectly, when he or she consciously engages in the fullest exploration of the interpretative space, which, depending on the nature of the composition, might include extra-musical or theatrical elements or a heightened level of intellectual challenge in terms of understanding the conceptual space.[44] In this sense, the current stage in the development of the cello is a dynamic one, during which the very notion of what constitutes cello playing is being expanded. At the same time, I firmly believe in the value of instigating a re-evaluation of established techniques with a view to integrating them as organic components that provide a significant part of the momentum for this expansion.

Bibliography

Alexanian, Diran, Complete Cello Technique: The Classic Treatise on Cello Theory and Practice (New York: Dover Publications Inc., 2003)

Berry, Michael, ‘The Importance of Bodily Gesture in Sofia Gubaidulina’s Music for Low Strings’, Music Theory Online 15. 5 (2009)

Biber, Julia A., ‘Ten Etudes for Solo Cello by Sofia Gubaidulina’ (DMA, City University of New York, 2016) CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1485

Belonosova, I. V., ‘Grigory Ilich Pekker: Commentary to Biography (1916-1934)’, Mezhdunarony nauchno-issledovatelskii zhurnal. 9. 51, 4 (2016) https://research-journal.org/art/grigorij-ilich-pekker-kommentarij-k-biografii- 1916-1934/ doi: 10.18454/IRJ.2016.51.124 [accessed 18 July 2019]

Boykova, Vasilisa, ‘Extended techniques in XX century: a case of systematisation’, Nauchnyj vestnik Moskovskoj konservatorii (Journal of Moscow Conservatory), 4, 2012 http://nv.mosconsv.ru/rasshirennyie-tehniki-igryi-na-violoncheli-v-xx-veke-opyit-sistematizatsii/

Chang-Park, Didi, ‘Sept Papillons: A Performance Process’ https://www.academia.edu/31915925/Sept_Papillons_A_Performance_Process [accessed 2 August 2019]

Ewell, Philip A., ‘The Parameter Complex in the Music of Sophia Gubaidulina’, Music Theory Online, 20. 3 (2013)

Fallowfield, Ellen, ‘Cello map: a handbook of Cello technique for performers and composers’ (PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, 2010)

Freedman, Lori, ‘Potent’, in Sharon Kanach, ed., Performing Xenakis (New York: Pendragon Press, 2010)

Grigoriev, Vladimir, Methodology for Teaching Violin (Moscow: KLASSIKA-XXI, 2006)

Gubaidulina, Sofia, 10 Preludes for violoncello solo, revised version 1999 (Hamburg: Edition Sikorsky)

Helm, Everett, ‘Music in Yugoslavia’, The Musical Quarterly, 51. 1 (1965), 215–224

Hill, Jackson, ‘Changeant für Violoncello und Orchester (1967-68) by Milko Kelemen’, Notes, 27. 2 (1970), 339–339

Kurtz, Michael, Sofia Gubaidulina, a Biography, trans. Christoph K. Lohmann (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2007)

Le Guin, Elizabeth, ‘“Cello-and-Bow Thinking”: Boccherini Cello Sonata in Eb Major “Fuori Catalogo”’, ECHO, 15.1 (2019), http://www.echo.ucla.edu/cello-and-bow-thinking-baccherinis-cello-sonata-in-eb-minor-faouri-catalogo/ [accessed 12 August 2019]

Lehnhoff, Charlotte, ‘The Popper School of Cello Playing’, Internet Cello Society, http://www.cello.org/Newsletter/Articles/poppercl.htm [accessed 12 January 2018]

Lim, Liza, ‘A mycelial model for understanding distributed creativity: collaborative partnership in the making of “Axis Mundi” (2013) for solo bassoon’, 6, in CMPCP Performance Studies Network Conference, Cambridge, 4–7 April 2013, University of Huddersfield Repository

Mantel, Gerhard, Cello Technique: Principles and Forms of Movement, trans. Barbara Haimberger Thiem (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995)

Matossian, Nouritza, Xenakis (Lefkosia: Moufflon Publication, 2005)

Nakipbekova, Alfia, ‘Performing Contemporary Cello Music: Defining Interpretative Space’ (PhD thesis, University of Leeds, 2020)

——– ‘Nomos alpha by Iannis Xenakis: reflections on interpretative space’, in A. Nakipbekova (ed.), Exploring Xenakis: Performance, Practice, Philosophy (Delaware: Vernon Press, 2019)

Orning, Tanja, ‘Pression – a performance study.’ Music Performance Research, 5 (2012), 12-31

Palm, Siegfried, Studien zum spielen neuer Musik für Violoncello (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1985)

Piatti, Alfredo, Twelve Caprices Op. 25 (Leipzig: Edition Peters)

Popper, David, Hohe Schule des Violincellospiels, Op. 73 (New York: International Music Company, 1982)

Solomos, Makis, ‘Nomos alpha. Remarks on performance’, in Exploring Xenakis: Performance, Practice, Philosophy, A. Nakipbekova, ed., (Delaware: Vernon Press, 2019), pp. 109-127

Terje, Moe Hansen, ‘A Modern Approach to Violin Virtuosity’ (Warner/Chappell Music, 1997)

Tortelier, Paul, How I Play, How I Teach (London: Chester Music, 1975)

Varga, Bálint András, Conversations with Iannis Xenakis (London: Faber & Faber, 1996)

Venturini, Adriana, ‘The Dresden School Of Violoncello In The Nineteenth Century’ (BA thesis, University of Central Florida, 2009)

Welbanks, Valerie, ‘Foundations of Modern Cello Technique; Creating the Basis for a Pedagogical Method’. PhD thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London, 2017

Xenakis, Iannis, Nomos alpha, score (London: Boosey & Hawkes, 1967)

Video

Lim, Liza, Best Practice in Artistic Research in Music Keynote – Professor Liza Lim October, 2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JoD_eKVywGY&t=687s [accessed 12 May 2019]

Endnotes

[1] Liza Lim, ‘A mycelial model for understanding distributed creativity: collaborative partnership in the making of ‘Axis Mundi’ (2013) for solo bassoon’, p. 6, in CMPCP Performance Studies Network Conference, Cambridge, 4–7 April 2013, University of Huddersfield Repository.

[2] For example, Liza Lim’s compositions for cello Invisibility (2009) for solo cello and two bows, and an ocean beyond earth (2016) set up in an installation prepared with thread and violin, ‘extends’ the cello beyond its physical boundaries.

[3] Tanja Orning explores this work as a unique example of using the instrument in the context of the musique concrète developed by Pierre Schaeffer: ‘Inspired by Schaeffer’s ideas, Lachenmann adapted his technique for use not with electronic objets musicaux but with acoustic instruments. He developed a rich palette of sounds, many of them physical and almost mechanical sounds similar to Schaeffer’s real-world sounds. […] In Pression the cello as the sound source we know is eliminated, so the cello as a traditional instrument with all its connotations and history is on one level erased through this compositional method. In this respect, we can say that Lachenmann has liberated not only the sounds, but also the instrument and the performer from the weight of the history of the cello’. Tanja Orning, ‘Pression – a performance study.’ Music Performance Research, 5 (2012), pp.12-31(p.15).

[4] Welbanks, ‘Foundations of Modern Cello Technique’, p. 33.

[5] See Nouritza Matossian’s detailed analysis of the mathematical concepts and structure of the composition in Xenakis (Lefkosia: Moufflon Publication, 2005), pp. 231-239. Matossian asserts: ‘In fact to experience a performance of Nomos alpha is to see the intricacies and particularities of cello-playing under a microscope’, p. 237.

[6] In my Doctoral Thesis ‘Performing Contemporary Cello Music: Defining the Interpretative Space’, University of Leeds (2019), I explore the notion of the interpretative space as an integrated domain of physicality and artistry, the ‘technical’ and ‘expressive’ elements in performance. In this article I am isolating the term ‘techniques’ for the purpose of discussion rather than demarcating a separate area in cello playing. This also applies to the ‘technical studies’ as part of mastering the cello. See also Alfia Nakipbekova, ‘Nomos alpha by Yannis Xenakis: reflections on Interpretative Space’, in A. Nakipbekova (ed.) Exploring Xenakis: Performance, Practice, Philosophy, (Delaware: Vernon Press, 2019), pp. 89-107.

[7] Among the collections of studies still widely used in cello pedagogy are: David Popper’s Studies Op.73, the Twelve Caprices Op. 25 by Alfredo Piatti various editions of studies by Friedrich Dotzauer, Schröder’s 170 Foundation Studies; among the methodology publications: Diran Alexanian, Complete Cello Technique: The Classic Treatise on Cello Theory and Practice (New York: Dover Publications Inc., 2003), Paul Tortelier, How I Play, How I Teach (London: Chester Music, 1975), Gerhard Mantel, Cello Technique: Principles and Forms of Movement, translated by Barbara Haimberger Thiem (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995). In teaching my advanced students, supplementary to the Popper and Piatti Studies, I use my arrangements of the Niccolò Paganini 24 Caprices and the method by Terje Moe Hansen, ‘A Modern Approach to Violin Virtuosity’ (Warner/Chappell Music, 1997) that I adapted for cello.

[8] In addition to traditional scales and double stops I include variety of types of scales outside the usual format: pentatonic, diminished, whole-tone, symmetric and extended scales-exercises, i.e. microtonal and combinatorial, as well as variety of patterns, 7th chords in non-linear progressions. This helps to ‘loosen up’ the basic ‘geographical’ sense of the fingerboard and connect to non-classical styles, improvisation and new music expression. For a comprehensive list of the twenty-century etudes for cello see Welbanks, ‘Foundations of Modern Cello Technique’, pp. 283-285.

[9] Adriana Venturini, ‘The Dresden School Of Violoncello In The Nineteenth Century’. 2009, BA Thesis, University of Central Florida.

[10] The examples of the etudes that are suited (with minimal fingerings alterations) for practising chromatic sequences: Nos.12 (C to C#, B), 33 (D to C#, Eb), 13 (Eb to E).

[11] Charlotte Lehnhoff, ‘The Popper School of Cello Playing.’ Internet Cello Society.

http://www.cello.org/Newsletter/Articles/poppercl.htm [accessed 2 February 2017].

[12] Personal communication in a masterclass.

[13] Vladimir Grigoriev, Methodology for Teaching Violin (Moscow: KLASSIKA-XXI, 2006), p. 151.

My translation from Russian.

[14] This is the central principle of movement in the art of Tai Chi, an ancient form of Chinese martial arts. In relation to playing cello, Elizabeth Le Guin describes this mode of ‘balancing and centering’ as ‘active stillness’. Elizabeth Le Guin, ‘“Cello-and-Bow Thinking”: Boccherini Cello Sonata in Eb Major “Fuori Catalogo”’, ECHO, 15.1 (2019), http://www.echo.ucla.edu/cello-and-bow-thinking-baccherinis-cello-sonata-in-eb-minor-faouri-catalogo/ [accessed 12 August 2019].

[15] Best Practice in Artistic Research in Music Keynote – Professor Liza Lim, October, 2017, at 11’35”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JoD_eKVywGY&t=687s [accessed 12 May 2019].

[16] Lori Freedman, ‘Potent’, in Sharon Kanach (ed.) Performing Xenakis (New York: Pendragon Press), 2010, pp. 3-10 (p. 3).

[17] Nouritza Matossian depicts the units as ‘an arduous procession of 192 micro-events, one self-contained unit treading upon the heels of the next, fracture and splinter the temporal course of the music into innumerable fragments and speeds which add to the technical difficulty of playing the piece.’ Matossian, Xenakis (Lefkosia: Moufflon), 2005, p. 238. Makis Solomos identifies 144 events, asserting that the piece ‘remains “difficult” for the listeners: it is submerged in the torrent of 144 micro-events, an extreme fragmentation accentuated by the presence of many silences and tempered only by a few fuller gestures’. Solomos, ‘Nomos alpha. Remarks on performance’, in Exploring Xenakis, pp. 109-127, p.109.

[18] For an analysis of this approach, see my Doctorate Thesis ‘Performing Contemporary Cello Music: Defining Interpretative Space’, Chapter 1; see also ‘Performing Nomos alpha by Iannis Xenakis: reflections on interpretative space’, in Exploring Xenakis, pp. 89-107.

[19] See Iannis Xenakis, Nomos alpha, score (London: Boosey & Hawkes, 1965), bars 80-94

[20] See endnote 19

[21] Siegfried Palm, Preface to Studien zum spielen neuer Musik für Violoncello (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel (1985), p. 3.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Palm, ‘Remarks and Explanation of Signs, 5. Kagel SIEGFRIEDP’, in Studien zum spielen neuer Musik für Violoncello, p. 2.

[24] Everett Helm, ‘Music in Yugoslavia.’ The Musical Quarterly, 51. 1 (1965), pp. 215–224 (p. 221). See also Jackson Hill, ‘Changeant für Violoncello und Orchester (1967-68) by Milko Kelemen’, Notes, 27. 2 (1970), p. 339.

[25] As elucidated by the composer, ‘The etudes are a sketch of an artistic production. But apart from this, I really wanted varietal types of articulation for cello also to fit into this idea. From one point of view it’s an artistic sketch, but from another point of view, it’s definitely a sampling of various types of cello sounds […]. I examine it this way […] these were distinctively my etudes for future pieces.’ Julia A. Biber, ‘Ten Etudes for Solo Cello by Sofia Gubaidulina’ (2016). CUNY Academic Works, pp. 27-28. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1485 Thus, in these compositions the performer and composer ‘meet’ in an indirect collaboration, participating in a continuously evolving process of exploration of the cello.

[26] See Belonosova I. V., ‘Grigory Ilich Pekker: Commentary to Biography (1916-1934)’, Mezhdunarony nauchno-issledovatelskii zhurnal. 9. 51, part 4 (2016), https://research-journal.org/art/grigorij-ilich-pekker-kommentarij-k-biografii-1916-1934/doi:10.18454/IRJ.2016.51.124 [accessed 18 July 2019]. My translation from Russian.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Michael Kurtz, Sofia Gubaidulina, A Biography, trans. Christoph K. Lohmann (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2007), p.132, quoted in Welbanks, ‘Foundations of Modern Cello Technique’, p.317.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid., p. 28.

[32] Ibid., p. 29.

[33] Ibid., p. 30.

[34] Matoussian, Xenakis, p. 238.

[35] Orning, ‘Pression – a performance study’, p. 14.

[36] Grigoriev, Methodology for Teaching Violin, p. 147.

[37] I discuss this subject in ‘Performing Nomos alpha by Iannis Xenakis: reflections on interpretative space’, in Exploring Xenakis, pp. 98-100.

[38] Matossian, Xenakis, p.238.

[39] Varga, Bálint András, Conversations with Iannis Xenakis (London: Faber & Faber, 1996), pp. 64-66.

[40] Michael Berry, ‘The Importance of Bodily Gesture in Sofia Gubaidulina’s Music for Low Strings’, Music Theory Online, 15.5, 2009 http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.09.15.5/mto.09.15.5.berry.html [accessed 17 August 2019].

In parallel, this sense of the intimate bond with the instrument in Popper’s Etude No. 9 where the motion of the left hand executing the melodic line in double stoppings as if ‘caressing’ the strings, integrates the two distant ‘technical’ methods into the universal principle of the cello-playing experience.

[41] Kholopova, Sofia Gubaidulina: Monografiia 137. Ewell, “The Parameter Complex,” paragraph 13, cited in Biber, 32.

[42] Didi Chang-Park investigates approaches to performance from the perspective of a classically trained cellist, with ‘a tendency to aspire for a certain ideal sound’, drawing parallels with literature: ‘In claiming that “everyone stutters,” […] Dworkin immediately displaces the stutter from the limited realm of defect or disability, placing it instead in all bodies (Dworkin 166). […] And it is in this sense that I want to explore the universal stuttering of the body-and-instrument, a living and inanimate body subsumed into one performative entity that stutters two-fold, as a body that amplifies its own stuttering motions as it manipulates an instrument, and the stuttering of the instrument itself as it is manipulated by the body’. Chang-Park, ‘Sept Papillons: A Performance Process, 2017, https://www.academia.edu/31915925/Sept_Papillons_A_Performance_Process [accessed 2 August 2019].

[43] Orning, ‘Pression – a performance study’, p. 22.

[44] The subject of theatricality in new music, a phenomenon that has developed into an important part of contemporary performance, is nevertheless beyond the scope of this article.