Working Together

– an interview with Roberto Fabbriciani

Read as PDF

Table of Contents

DOI: 10.32063/0405

Bjørnar Habbestad

Flutist, curator and researcher educated in Bergen, London and Amsterdam. Habbestad has performed across Norway and Europe with a repertoire ranging from contemporary classics such as Ferneyhough and Sciarrino through electroacoustics, improv and noise. His research at NMH targets composer-performer collaborations. Habbestad is the current Artistic Director for nyMusikk.

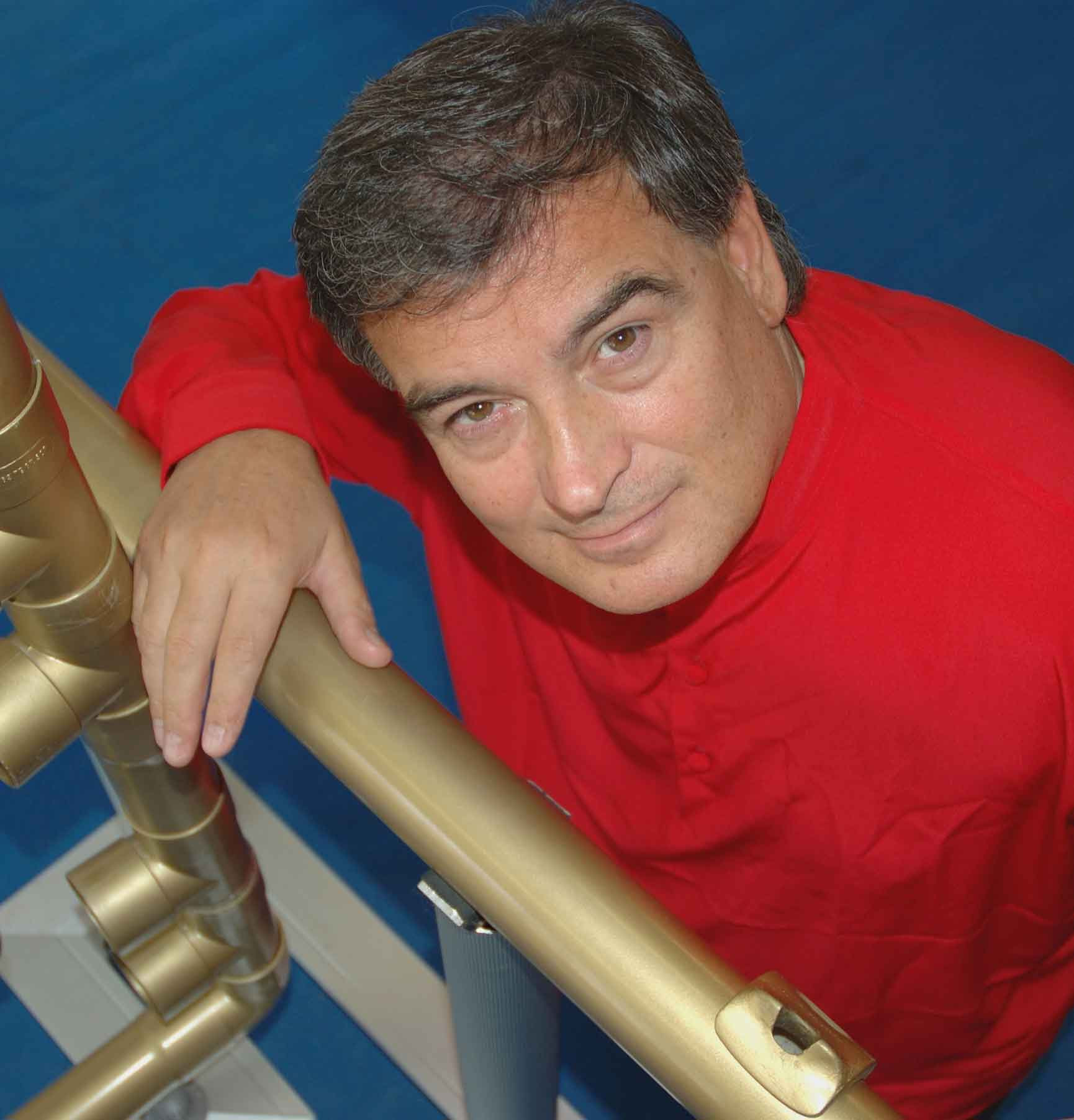

Roberto Fabbriciani

Flutist, improvisor, composer and instrument inventor. Collaborator and performer of the music of a cross-section of musical modernists from Berio, Boulez and Ferneyhough through Maderna, Nono and Sciarrino. As a soloist he has given recitals and performed with major orchestras and conductors around the world, recorded more than 80 albums, and taught at several conservatories. Fabbriciani is also the inventor of the hyperbass flute, for which he has composed and recorded several works.

by Bjørnar Habbestad

Music & Practice, Volume 4

Exploratory

Introduction

The list of flutist Roberto Fabbriciani’s premieres and collaborations is too long to itemize here.[1] His sound and technique have inspired a host of the most prominent post-war composers, ranging from first-generation modernists like Berio, Boulez, Ligeti, Cage and Stockhausen, through Asian composers like Hosokawa, Takemitsu and Yun to the second-generation or post-modernists like Ferneyhough and Rihm. Despite this broad scope and more than 80 recordings to his name, his most important is probably his close collaborations with his countrymen Salvatore Sciarrino (1947–) and Luigi Nono (1925–1990). The relationships between the three, and their interaction in the development of a body of works that can be said to have redefined the sound of the flute as a musical instrument, sets the frame for our talks and discussions.

This interview took place over several months,[2] starting in Fabbriciani’s study in Florence, surrounded by books, scores and posters. Over four intense hours we played through Sciarrino’s Opere per flauto vol. 1. Talks, espresso and a meal followed, and I returned the next day to work on Das atmende Klarsein by Nono. After the meeting in Florence, we corresponded by email until I returned to Italy five months later to hear Fabbriciani premiere a new work by Nicola Sani at the Venice Biennale. These meetings – with or without flutes, in person or in writing – were complicated by our language barrier. A street café at the piazza in front of my hotel was host to our lengthy talk on the second occasion, when I was armed only with a Dictaphone. We communicated in two or three languages and none of them are thoroughly shared between the two of us. Still, as I left Venice after our long espresso-fuelled talk, I made a note to myself stressing the paradox of understanding so much from so little.

The following is a synthesis of transcriptions and translations from our diverse meetings, organized thematically for the sake of clarity.[3] Some keywords keep resurfacing as we get to know our shared interests in different notions of sound, of creative processes and of performing composed as well as improvised music for flute: the sonic orientation in contemporary music, the act of listening, the importance of experimentation and the necessity of risk-taking. But first and foremost we talk about the creative and musical potential in collaboration.

The sound of the twentieth-century flute

Bjørnar Habbestad It’s a common notion that the flute repertoire of the twentieth century emanates from Debussy’s solo piece Syrinx, and the lush sonority found in his orchestral flute solos of Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. But today, timbral transformation takes place not as an exotic embellishment of certain pitches, but as compositional matter in its own right. Looking back at your many collaborations, how would you describe this change in the sound of contemporary music?

Roberto Fabbriciani I think each era has changed the sound of music. In our time, it changed when it was affected by atonality and the development of instrumental techniques and effects. Great composers have always looked ahead, thanks to the way they imagined sound. The flute, a monodic and cantabile instrument, has now become full of sonic resources, something that also has changed the point of view of composers.

How do you think this has changed the role of the performer?

After 1960, music became more standardized, because composers were looking for a common, ideal language that was no longer personal or even national. Although each one tried to use personal techniques, this does not mean that they did not adhere to certain common instances. Performers began to have a different and a more active role, not only as they tried to cater to more sophisticated sound expectations, but also by proposing solutions and innovations.

You have personally contributed to advancing the sonic repertoire of the instrument. Which techniques do you find most important or influential for music today?

I think the most influential techniques in today’s music are Sciarrino’s acoustic sounds and Nono’s innovative use of amplification and live electronics. In the 1960’s I started to develop multiphonics, cooperating with Bruno Bartolozzi[4] amongst others. My teacher Severino Gazzelloni and the composers I was in touch with, such as Bruno Maderna,[5] influenced this research, which led me to reinventing the flute.

Do you find that these developments in instrumental technique have found their way into conservatories and music academies?

Not yet! As far as I can see, students in conservatories study mainly historical music literature. There are some departments where contemporary music is studied, but rarely specifically instrumental and for flute. I think new music needs performers to play an active role. They may not only be performers, but also co-creators, as they now have many more opportunities to create sounds than in the past. Here, the relationship between composer and performer becomes absolutely and necessarily complementary and interactive. The fantastic and boundless ideas of the composer arouse the performer’s creativity and push him/her to the extreme and unusual boundaries of his/her art using the instrument.[6] The performer’s ability and imagination to conceive and to create new sounds becomes very important in the development of and innovation in the musical language.[7] Nono spoke of my sound as ‘surprising innovations’ and wrote that ‘he [Fabbriciani] was … immersed in the Freiburg studio, and I [Nono] was immersed in his mastery’. Maybe this way of thinking should find its way into the curriculum.

This makes me think about a statement from Luciano Berio, talking about ‘a different virtuosity’ – a virtuosity of sound[8]. Did you discuss this with him?

Berio’s concept is definitely well placed. I had the pleasure to play Sequenza I for him countless times. His writing stimulates the imagination and inventiveness of the interpreter. It promotes interpretative freedom, a crucial feature of the aesthetics that inspires Sequenza I. It addresses the problems of a form of polyphony based on the multiplicity of the action. Berio used the flute to its full potential. He was interested in the phonic quality of the sound material, both acoustic and linguistic – i.e., its evocative meaning, resulting in the rhetoric of pastoral metaphysics. With respect to the interpretation of Sequenza I, Luciano Berio told me that beyond the accurate research of the technique and the phrasing, it would be necessary to listen to Severino Gazzelloni.[9]

Did you also discuss with him the background for the revised version of the Sequenza (1992) where he reconstructed the rhythmic structure, from a space-time notation to a traditional metric notation?

At the occasion of one of our concerts, Luciano Berio expressed some dissatisfaction with the manner in which many flutists would perform the Sequenza I. In our discussion, I mentioned to him the idea of a version with traditional notation to facilitate the preparation of the piece for younger performers.

Do you know if Berio discussed this with Gazzelloni? Do you know what he thought about this change?

Absolutely no. Gazzelloni loved the time-space writing as it allows more freedom and imagination. Also, the original and amicable dedication ‘a Severi’ is a sign of great friendship.

Speaking of Gazzelloni, Italian flautists seem to connect more strongly to contemporary music, is this a coincidence? Are there any reasons for this?

Well, this is absolutely true regarding Gazzelloni. He was my teacher and he introduced me to the major composers of the time. I think that because of the direct contact, certain performers can consider themselves as collaborators of the composer, that they take part in the creation of new music. The fact that some flautists are interested in playing contemporary music is quite another matter. This does not necessarily mean working in close contact with the composer and taking part in the creation of music.

Is there ‘an Italian sound’ that has developed, or is this sonic development outside of the national trends?

I think Bruno Maderna gave the best answer when he declared the need to return to melody because we are Italian and that this is our essence; a message that has been quite ignored. However, Italian music does show an inherent taste for lyricism. It is an atonal, special, avant-garde lyricism, but still something that distinguishes our music from the others.

There also seems to be a strong connection between Italian composers and the flute, as so many composers here have contributed to the solo literature: Berio, Sciarrino, Nono, Franscesconi, Fedele, etc.

No doubt about it. I think I have contributed to the diffusion of music for flute thanks to a relationship of mutual respect and trust with the composers. Good collaborations arise from a common intent between performer and composer. I could mention the collaboration with Luigi Nono during the writing of Das atmende Klarsein. First we tried at home, without using electronic techniques, and we improvised with acoustic sounds in search of sound solutions. Then, after choosing some of those acoustically performed materials, we experimented with them using electronics. Some were interesting and some were not. Therefore, a further choice was necessary to draft some kind of provisional score. We produced the piece only after some performances.

So the process of collaboration continues after the score is finished ?

In some cases, certainly.

Collaboration

Performers are thought to be ‘true to the work’ – that they have an ethical obligation to put the identity of the work before their identity as artists. This means that there is an ideal where we aim at meeting the new work or the collaboration without bias, trying to understand and relate to it without prejudice. Still, to what extent do you find that you bring something into all musical situations – a sound, an attitude, a material?

Directly, such musical material suggests new ways of expression. By a new technique, yet untested, you can discover unexplored sound worlds.

Do you think that such an artistic bias can be useful in collaborations with composers?

Rather than prejudice you need an open mind, especially for new music. This important feature allows the collaboration not only among composers but also between author and interpreter.

In improvised music the ethic-of-the-work is exchanged with an ethic-of-the-performer. Could you envision this ethic within the framework of contemporary music?

Certainly. In contemporary music there is a certain randomness, controlled or free. But beyond this technique, today, the role of the interpreter is more creative, as there are many sounds which require a performer’s creative intervention, such as extended techniques. It is true that this exists in all historic repertoire, as a true interpreter is not a mere executor of notes and symbols, but contemporary aesthetics also refers to the uncertainties and details of sound emission that are not always provided by the composers, on which you can greatly diversify the interpretation of a piece.

How do you feel about ownership to your sounds when collaborating with composers?

I really hope to give this sound to composers, and that everyone can use these new sounds in their music. They’re really new avenues.

But in the contemporary music scene, both the economic and cultural capital often follow the composer, not the performer. In your experience, to what extent is the role of the performer acknowledged by composers, publishers and the musical world in general?

Well, the role of the performer-interpreter, who is a co-author, is often not recognized. This is also a matter of knowledge. It is always necessary to work together, to learn to understand; this is the same issue for all composers: for Nono, for Berio, for all composers of direct experimental music. Learning, working together, knowledge. This is necessary, and composers today know what prestige is but have no concept of the workshop. That is the historical workshop, the Renaissance workshop, like Michelangelo’s. Today we have a similar problem. This is necessary for the future: workshops and direct collaboration, absolutely. What do you think?

In my experience, the relationship between my own and a composer’s contribution in workshop situations are often unclear and unregulated. And in some cases my role, as co-creator or contributor, become highly downplayed.

Yes, yes, this is a problem. It happens to me too. But for me this is not so important, for me it’s history continuing. It was the same problem with Sciarrino. I think what matters, what’s important is the time of the story. For example, All’aure in una lontananza, the first piece with Sciarrino … in 1976 … it revolutionized flute literature. At the time, I didn’t have a ‘Fabbriciani’s method’, I didn’t have anything to publish, but it wasn’t necessary because of the time of the piece, the history. And yes, I could or should have published a book sooner, but today I think it wasn’t necessary for history, because the piece is history itself.

That’s a very generous approach.

Well, thanks. Today I think like this, at a different moment perhaps? But today it’s not necessary – today everything’s clear. That’s the way it is, and perhaps we’ll have the same problem with my hyperbass[10] sounds because that was the first instrument and everything that’ll be new in the future for that music builds on this. But that’s the way it is, isn’t it?

If I look at the repertoire from this period that you mention, from 1974–1978, it really looks to me like the sound of the flute is changing, something new is happening at this time.

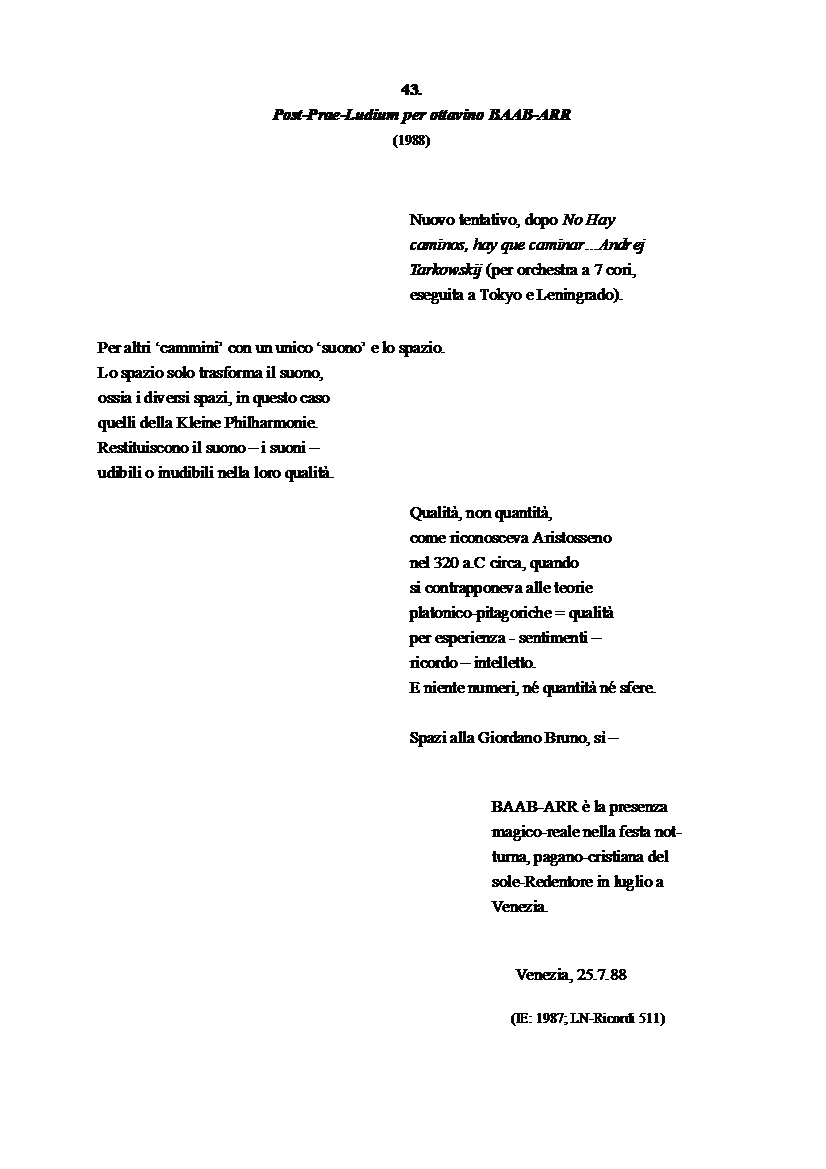

Yes, at the time, it changed; it definitely was a turn. These were very important years because history was changing, the sound was changing. Experiments, research, casual meetings, it was incredible, although many composers couldn’t write, they didn’t formulate this music perfectly. But even earlier – the late 1960s – 1968, 1969 – during this time the way of thinking changed, the way of thinking about music and playing it. I think it was a very important transition time. At the time I was collaborating with Sylvano Bussotti.[11] A great composer of the time, he was one of the most experimental, but his writing wasn’t very detailed – it was more about the beautiful sign: in painting, in writing. Very elegant, but not detailed like Brian Ferneyhough, for example, not analytical. Before Sciarrino, with Bussotti, we experimented – very interesting and important experimentations – but we didn’t write them down.

So you think the score becomes important as an historical document then, a documentation of what actually took place?

Yes, exactly. In those years, with Sylvano Bussotti, I experimented a lot, but we didn’t detail these on paper so much.

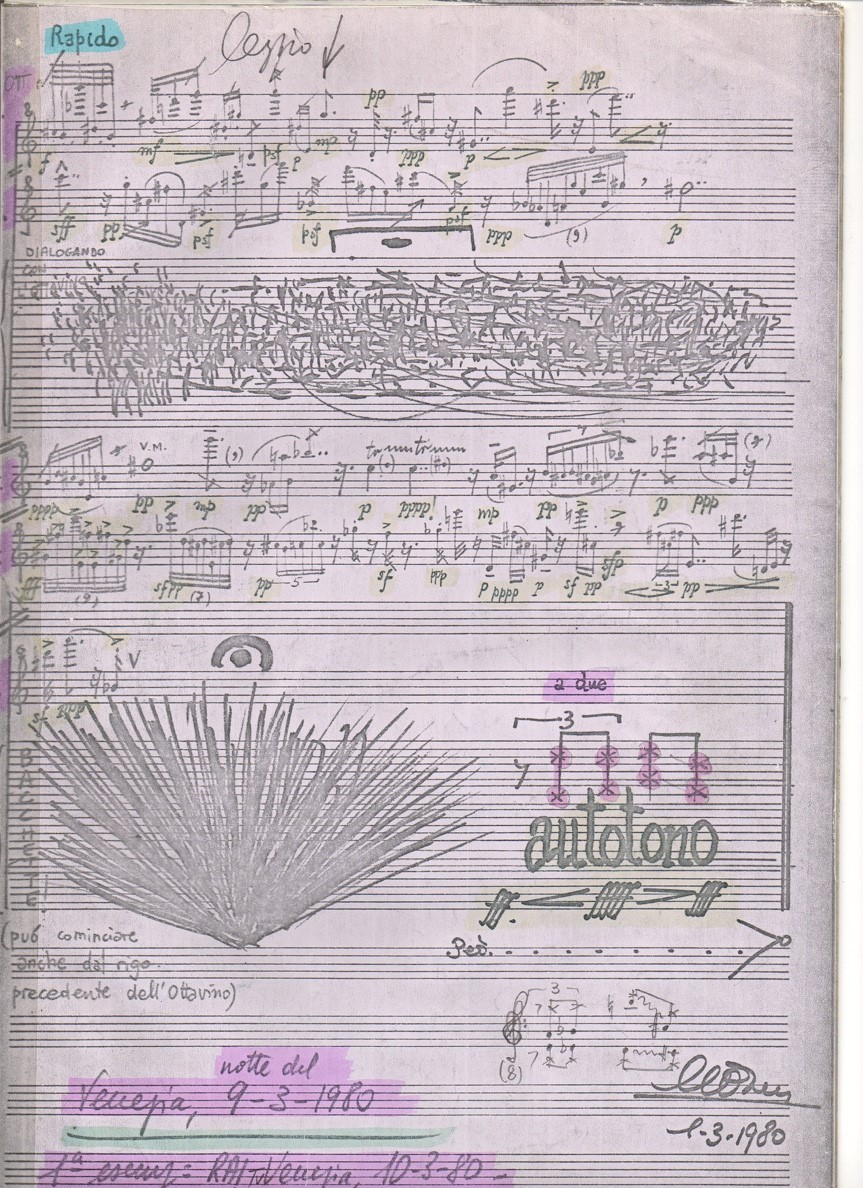

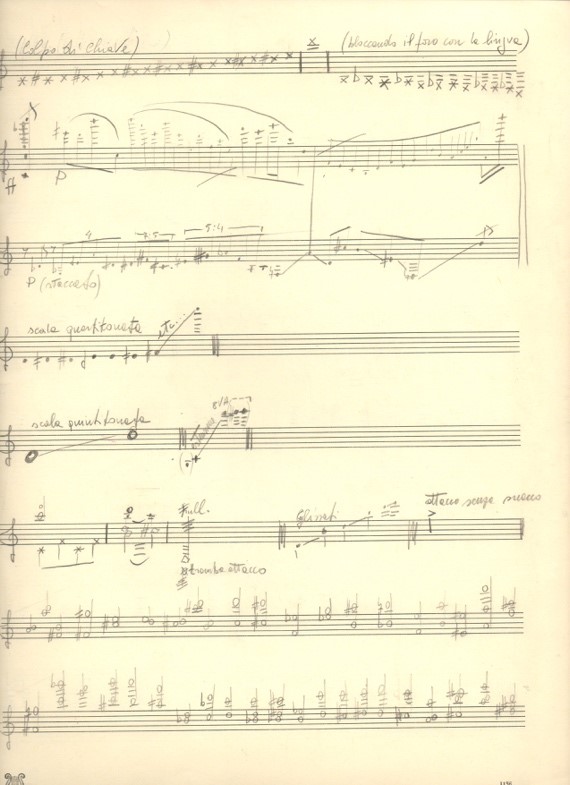

Figure 1 Excerpt from manuscript, Sylvano Bussotti: Autotono (1980). From the private collection of Roberto Fabbriciani

You know, ten years before I started working with Sciarrino, I collaborated with Bruno Bartolozzi, who wrote the well-known manual New Sounds for Woodwinds.[12] For me this was the first experience with a composer. He was perhaps not a great composer, but he was a great musician. And his book was a very important achievement at the time. We met when I started playing in the orchestra Maggio Musicale Fiorentino in 1964, I was very young, only 15, and the average age of the musicians was perhaps 64 (!). But there he was, Bartolozzi, as a violinist. He would invite me to his house and say ‘Roberto, play’. At the time I played many, many multiphonic pieces – I had a large catalogue of repertoire then, and we worked together. He was an enthusiastic man, and I wrote for him the quarter-tone scale, not only for open-hole, but also for closed-hole flute. This experience was very interesting for me. I learned a lot, it is a good cultural baggage. And it’s not just casual, I mean, it’s solid knowledge.

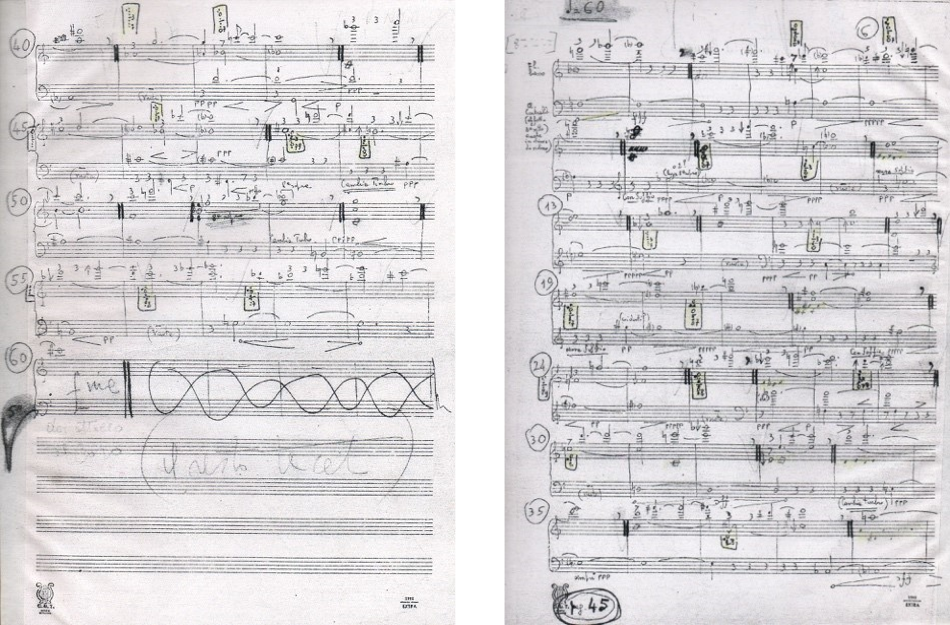

Figure 2 Multiphonic notation from collaboration with Bruno Bartolozzi. From the private collection of Roberto Fabbriciani

Actually, we played only by ear, we didn’t have any electronic instruments at the time. For the multiphonics we had to listen; one pitch at the time. We would experiment carefully and with an attentive ear, trying the same position but changing the air and embouchure pressure, and the position of the lips on the mouthpiece. The result would change, and it was difficult to determine precisely the pitches. A mad work, extraordinary, but Bartolozzi … he had an orecchio assoluto, do you understand? Perfect pitch.

Are you quoted as a source in any of his publications?

Yes, as a performer of his pieces for flute, e.g. Cantilena for alto flute, Per Olga for solo flute and Sinaudolodia for four flutes, which he all wrote for me. But not for the publications. I soon left Florence to move to Milan to the La Scala Orchestra and I did not have the opportunity to go any deeper in my work with Bartolozzi, who continued with my fellow flautist Pier Luigi Mencarelli. But I still have handwritten notes from our sessions (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 3 Sketch from collaboration with Bartolozzi. From the private collection of Roberto Fabbriciani

Improvisation and risk-taking

The experiments that don’t manifest themselves in scores, but remain important for how composers and performers alike think and listen intrigue me. I find there is too little value given to these types of processes. If we narrow this down even more, to the moment when you experiment with the instrument, how do you think about creating something new? What kind of process is this? What takes place?

It’s a very interesting question. I have never thought of this in this way, but I think I to a certain extent have followed the norm. However, this makes me reflect because sometimes I went very far, a long way, and I got extraordinary results. But I’ve never thought to record or to write it down. And spontaneous improvisation is a very important way to express oneself, because all the knowledge you have inside can be expressed in a liberating way. It can set you free and produce exceptional results. Especially when I play for myself. Of course I have improvised a lot for and with composers, for others, but that’s more constrained, you know? Your control is more constrained when you improvise for others.

So the improvisation becomes a way to condition your future behaviour?

Well, when you improvise with composers it’s more restricted. When I used to improvise for Nono I wasn’t thinking about him, I improvised freely, but there was still some constraint. Whereas when you improvise for yourself, on your own, it’s a much freer way to do it, it’s liberating, frei, you do it because you need it, as a need. It’s what I need to do for myself.

Nono must have been preoccupied with the relationship between thinking, listening and doing, between imagining and changing sound, and to me this seems to rely on improvisation. It seems natural that as a performer you have to develop that skill?

Exactly, and the levels of improvisation are endless, there are infinite possibilities. That is, you improvise in a traditional way, you can improvise historically, you can improvise in jazz and then you can improvise while experimenting. I think improvisation in experimentation is something more adventurous and you can really discover new worlds by doing so. But it’s also more difficult because you need not only the professional talent for playing, but also the ability to be creative and imaginative, with all its risks.

To me this is really of essence, the ability to risk something.

And this, this is a special talent that not all musicians have; not all musicians have this skill. You always need a lot of courage, and I always take chances, even during public performances, without problems. When I played the last piece for Nono, the Baab-Aar,[13] in Berlin, I didn’t have the score, no, I had nothing. This takes artistic courage, but also knowing how to manage risks, knowing how to take chances. This was a very important subject with Nono but also with other composers. Composers who love risks, adventure, and the chance to have a miracle – if it turns out well, it’s great, – but it can also be a disaster. But I’m a musician who takes risks, I take my chances, I love the risks and they are necessary. Yesterday (at a performance) I took a chance, a small one, but a risk nonetheless. And here is the difference – performers can be very good, professional, fantastic – but this is beyond academia, over academia, this is the difference between performers.

In your article ‘Walking with Gigi’ you write ‘Losing the fear of taking a wrong path allows error to become a further stimulus in the search for new horizons’. Could you expand a bit on how this process was for you? Have you always been fearless in this respect, or was there a development, a transition?

In the moment of losing the fear, you explore, and can also take wrong paths. But this is not bad art, because the wrong road led you to new knowledge that the right way would not have given you. Essentially, in creative exploration it is worth also to make mistakes as in the error you can find new knowledge. The error becomes a positive fact, generating new, right ways.

Earlier you wrote to me about how knowledge – of languages and technique – and creative imagination were the two most important types of skill when improvising. Do you not find that knowledge and risk-taking are opposites in this context?

I believe that knowledge provides the opportunity to arrive at ‘risk’. Without knowledge it is impossible to explore the unknown, and therefore risk itself.

Virtuosity of sound

Coming back to the role of experimentation, and its relation to the development of new sounds, how do you look upon the role of technical manuals in contemporary music? I have always felt there to be a contrast between the dry, seemingly objective way that this knowledge is categorized and presented and the creative and sonic potential or even freedom that lies within the sounds that are described.

Technique manuals are useful, they let you mature and grow from the instrument’s point of view. However, owning your sound own sound world is something quite different.

Could you elaborate on this? What does it mean to ‘own your sound world’? And how does that relate to the idea of ‘sonic virtuosity’ mentioned by Berio?

The new texts are useful for understanding, to indicate the paths of the new, but it is important to have a personality and a creative aspect in approaching their sound, to engage in works as complex as those by Nono, where virtuosity is given from the emission of the same sound, colour or timbre. The virtuosity in the works of Berio is very different and is derived from the idea of the romantic virtuoso interpreter, an idea that was expanded during the twentieth century. Or the virtuosity of great technique, high velocity or difficulties with reading. Nono’s virtuoso also works on just one sound that is constantly changing, on a single note. A virtuoso of quality and not quantity.

Do you think there is a relation between the development of electronic music and the instrumental sound of the contemporary flute?

All electronic music has influenced the way of conceiving the sound of acoustic instruments (like in some of the symphonic music by Ligeti, i.a.). It has made us rethink acoustic instruments in terms of their sounds and dynamics. Also, electronic instruments for sound analysis have created knew knowledge about listening, about sound awareness.

For me personally, electronic music led to new ways of listening to sound timbres and dynamics. Experimenting with sound and ‘seeing it’, not only listening to it, with instruments such as the Sonoscope[14] allowed me to explore and control all aspects of its emission.

As the name suggests, the Sonoscope makes us ‘see’ the sound. The emitted sound is captured by the microphone and ‘showed’ on the screen, in real time. By reproducing the sound image, the Sonoscope shows the transformation of the timbres and dynamics, and the emission control. It is a kind of ear training through sight.

The first collaboration – tracing Das atmende Klarsein

Your work with Nono seems to me to be a very good case study for investigating different types of interaction between performers and composers, and more specifically, the process of creating and performing Das atmende Klarsein in the period between 1980 and 1990 is a fascinating window into the methods and ideas of ‘the late’ Nono. Could you tell us something about the developments of this piece?

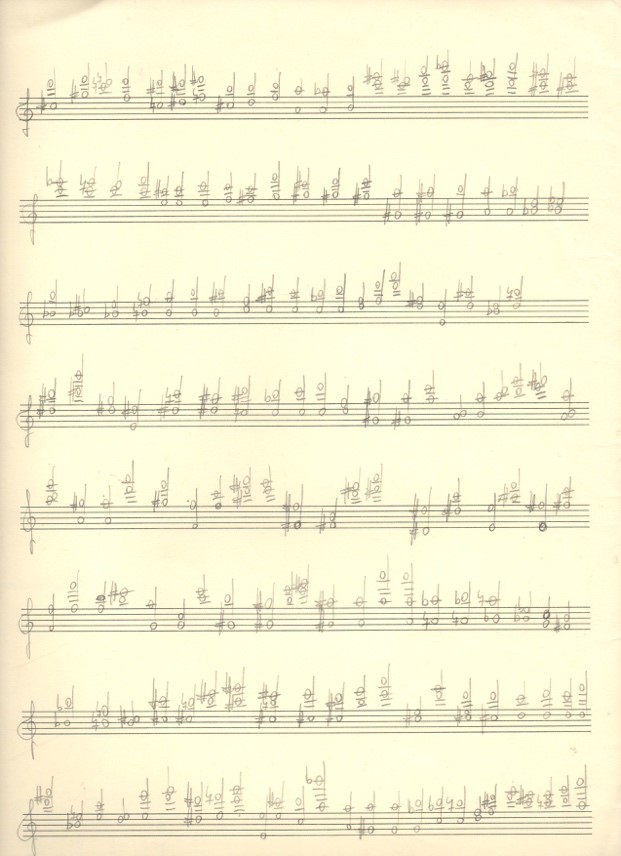

Das atmende Klarsein is the first of Nono’s compositions of the 1980s which lead to Prometeo.[15] The bass flute part underwent several changes and cuts with the various executions, and the handwritten flute part testifies to this transformation. After Luigi Nono and I visited Studio di fonologia musicale di Radio Milano in 1978, we went to the Experimental studio of the SWF Heinrich-Strobel-Foundation in Freiburg-Bresgau at the end of 1979.[16] Thus, the long collaboration with the Freiburg Studio began. I would improvise for Nono without electronic music, then I’d repeat with it. The first draft of Das atmende Klarsein was full of sound events. Even the succession of flute and choir moments was different. Materials became thinner and thinner with time and executions. I remember that in the first draft of Prometeo certain parts of Das atmende Klarsein were included in the score. The score would be reduced after the executions, and many parts would be eliminated.

Figures 4 and 5 Excerpts from unpublished version of a duet from Prometeo (1981 version). From the private collection of Roberto Fabbriciani

Looking at it from the outside, it’s almost as the performances could be seen as part of the creation process, as if the work originated not only from being composed but also from being performed.

Well, Nono’s reflective process was deep and slow. This is a good thing, although he could sometimes have second thoughts. Our experimentations were long, sometimes lasted for many days, when we recorded, catalogued and took notes about the results of our experimentations, in order to use them organically in the writing process. The gestation of the score was long and represented a radical turning point for Nono.

This is a radical conception of a work or a composition, that it holds the potential for continuous change and development. Did you discuss this idea with him in relation to the metaphor of the wanderer from Hay que Caminar, and his knowledge that traveling itself, and not the arrival, is the goal?[17]

Well I think that the metaphor of the wanderer is an assumption established by Nono looking back to this creative process.

How do you see future interpretations of Das atmende Klarsein? Should the last version from Ricordi be thought of as the ‘end’ of the development process, and should future performances adhere to this definitive edition and that recording?

The reference recordings of Das atmende Klarsein are certainly very useful as a study in performance practice. Some of Nono’s scores are not exhaustive, and so a performance tradition is necessary. Nono’s scores from the 1980s have often been changed since their first executions[18] until a level of conviction was reached. New performers will have to apply themselves to this performance practice, thinking of music as constantly transforming due to the risks in performing it and its interaction with live electronics and space. In Nono’s scores, performers are required to use their sound imagination, creativity and fancy. I think this is difficult, if not impossible, for performers who have not experienced a collaboration with the composer or with the original performers and technicians.

So how do you look upon future performances of these works, when the original performers and technicians are no longer active? Should the performance of Nono’s later works be a faithful recreation of the sound of the 1980s performances or should performances keep developing into something new?

I think it is necessary to create a performing tradition for these works. It is important that the interpreters have a solid cultural background and look for a philological interpretation. In this way music, with its parameters, its interaction with live electronics and space, is turning into something new.

How does the role of the tape relate to this issue?

The tape is a kind of ‘guided’ improvisation where the flautist interacts with the magnetic tape; sometimes following it and sometimes going against it, reinventing him- or herself each time. In that way you could say that it is similar.

This focus on the potential of change in the music, did it also affect how you would rehearse?

With Nono there wasn’t so much rehearsing, like many others do. Because a lot of rehearsals would take away the pathos of music. He worked a lot, but in different moments, in different moods and with great potential. The complexity was created mainly due to the diversity of the group of musicians and technicians used. We were very close-knit, in tune with each other so to speak, and this is very important, because we could express the thought of the composer more univocally, in a more cohesive way. I find this quite important, the relationship between the thought of the composer and that of the performers.[19]

What kind of complexity are you referring to here?

In a sense I have already answered; the complexity is given by the unusual, by the sound, the temporality suspended from the dynamics and not by what we commonly call the complex: a myriad of notes that on one side highlights the acrobatics of the interpreter and on the other allow the composer to present (familiar) techniques. This is far from Nono’s ideas.

I started alone with Nono, working together with him for three to four years. As the idea of a group was born, we thought about personalities, we were looking for the right people and the right type of performer for this situation. We needed people who were very close, psychologically and instrumentally, someone who could express this thinking. Later, after we wrote Das atmende Klarsein as a solo, the next piece, Io, fragment dal Prometeo was for two instruments. First I proposed my friend Ciro Scarponi,[20] then more and more musicians – [Giancarlo] Schiaffini[21] as the tuba player, and Susanne Otto as the singer – and we became almost a small ensemble. An ‘Ensemble of Trust’. And this is very important, trust is fundamental for this kind of work. Nono as a composer could be expressed more strongly because we all trusted each other. This is the compositional process, and then it all becomes easier, you know? Because it comes from provocation, from provocation to provocation: me, him, everyone.

An ensemble of trust

This ‘Ensemble of Trust’ proved vital for Nono’s entire output over his last ten years as a composer, and already in Prometeo I think you can see that there is a new performance practice approaching. The writing for orchestra, choirs, singers and instrumental soloists respectively is very different, also at the notation level. I like to talk about this as a layering of different musical practices. This quality, this richness is something I think partly lacks in current performances. Why do you think this is the case?

Now we face a very big problem, because Prometeo has completely changed. Actually, I don’t feel like talking about this. It’s important to say that I don’t speak for personal interest here. What is important is Nono’s music.

I think the quality of Prometeo. Tragedia dell’ascolto and the thinking of Nono as it comes through today is something very different from the original. Why? Because after Nono’s death in 1990, the score changed, as it wasn’t complete. Now it’s not complete either, many things are still missing … both performance-wise and sound-wise. There has been an adjustment, they have formalized an academic manner of playing this piece. This becomes a problem especially in the execution of the solo parts, because they are so much more complex than the way most performers today play: so safe, nice and sedate. These parts are not safe, there are many risks that I’m not hearing. But, again, this is verboten to me, I can’t talk about it.

Why?

Because they’d say it’s because I want to perform it myself. Well, I don’t. For me, playing is not necessary. I used to perform this piece, and it’s okay that it’s over. But the execution … there is no functioning performance tradition for this music. It has been cancelled, now it’s all academic, safe. There’s no fiction, there’s no philosophy, there’s no thought that goes into playing these solo parts. And the problem is especially clear for the soloists. That the orchestra plays very close to the way it’s written is a tradition, just as the for the specialist choir. But for the soloists – flute, clarinet, tuba, and the euphonium – it is very important that it’s done in a certain way. It should not be safe and sedate. Today it’s very sparse, bare, and that’s not the way it’s supposed to be. There is a great tension in Hölderlin’s part for example. This is not only a question about the technique, but there must be a sense of total instability while playing, a sense of utopia. And this I don’t hear today. It’s something undefined that puts you in a special mood, something that only a certain way of playing can give you. Not something an accountant, an engineer, a professor can do. This is pure utopia, just like Nono.

He was a utopian, unconventional, very deep, but a visionary man. And you, as a performer, you have to have a fair bit of vision too, you have to be a visionnaire too. For me, this is the vital difference: to be an Interpreter or a Performer. An interpreter is, as Cacciari says, one who accentuates the text, a cantore del testo, that’s the crucial role of the interpreter. The others are performers, the orchestra are performers, but the soloists can’t be performers, they have to be interpreters. Why? Because even the idea of Prometeo wandering among the islands, his adventures, they are pure utopia. He can’t just be someone who says, ‘Ah, yes, I’ve got a boat, I’ll go here, now I’ll go there’.

This is a psychological and material reduction of Prometeo. If you take the great poetry and deep philosophy of the text and music away from the music, it becomes a normal act. It is no longer a special one. And the Amsterdam Prometeo, the CD Prometeo, unfortunately, is a normal Prometeo.

I’ve even spoken about this for quite a while with Ingo Metzmacher, who is quite clever. When he performed Prometeo in Hamburg and later, after the CD, he called me and said: ‘Can you come to Hamburg to teach, to work … together with the soloist ensemble?’ I went there and the Prometeo in Hamburg was already better, but it’s difficult. It’s important to work together to explain, as a whole thought tradition, a tradition of execution, is partly missing, and this requires a lot of time to restore. It will take a long time for the ‘Nonoesque’ performance practice to become truly known and applied. Facing certain scores without owning these notions means that in the end, the music is not adhering to Nono’s thinking.

You keep coming back to this phrase, ‘working together’, with Bartolozzi, with Nono, Sciarrino, your fellow Nono-soloists and others. This interests me because I think your descriptions of this can tell us something about how we can play this music today. I find it not only interesting for documenting a historical practice, but relevant for how to continue to approach this music.

This, this is very important. The risk of this music becoming academic, like we discussed, is prominent. In Italian we say impoverimento, impoverishment. I think Prometeo is impoverished, precisely because the creative part is missing. Creativity can’t be constrained. The desire to limit and polish at any cost in order to create something is very unimaginative.

Do you think this kind of reduction is a general problem of contemporary music? Is the knowledge from the original interpreter(s) lost in the second generation of performances?

Well, the fear of losing something could be relevant in certain situations. But then again, perhaps in a different situation something changes and can become even better. But yes, in general, I think you lose something – not always, but in general. Because history becomes myth and then crumbles, it fades. In real time, a minute is 60 seconds, but one minute after 20 years is something different. Everything is reduced as time goes by, it is resized, there’s a reduction of everything. There could certainly be future performance where something gets better, but this we don’t know. But one thing is certain: something gets lost.

This is like baroque music – it was normal to improvise, to always change. Playing only what is written is a Romantic concept, and I think that the idea of freedom of expression was stronger in the past. It is a reduction of time. But I think that contemporary music is similar to baroque in certain ways. Certain techniques – in the flute, for example … there is the art of articulation of the tongue; there were many ways of attacking the sound, not just one system, like todays tucutucutucu–but rather lerelerelere, deredere, buruburu or duruduru … an infinite number of variations. And this is a freedom that today’s music, contemporary music has recovered.

Also, there were performers who created more personal positions. The creation, la création of the ancient performer is like Paganini for example. He had secrets, he used to break, to tear the strings, he’d play with just one string to show the possibilities. Paganini had a disease, a deformation, and nevertheless his hand did things that others normally couldn’t do, you know. So, in short, each performer would invent their system. Flutists like Briccialdi[22] was at odds with Boehm, because the latter used his system, the Briccialdi system. So everybody changed [it]. In the nineteenth century, there were thousands and thousands of system flutes, almost one system per maker. And Ziegler,[23] Briccialdi, then everybody would customise them with different materials, glass, metal, wood, ebony, all, many syst[ems], bone, ivory, all different with large holes, more or fewer keys, in other words different systems, especially in 1800, before the Boehm system was definitively adopted. So everybody created … that’s what I mean, a creativity of performers in order to gain new and different possibilities.

Do you think that the uniform sound ideal will become less influential?

Well, this works by assimilation – the French school, the German school, the Italian school etc. And especially for groups, to create orchestras, to create compact and homogenous groups. I think that the soloist, the creative performer should stand out from the crowd, out from an academic performance tradition. Today it’s needed as a novelty, but I think that there has always been an academic division, between normal and extraordinary performers who are creators of new sounds. There have always been utopian musicians, opening up the path of music. Extraordinary people, virtuosos, of romantische Virtuosität, like Ciardi[24] and Briccialdi. They were outside of the norm, because the orchestra would only play their Brahms and Schumann. So when De Lorenzo[25] appears, he’ll grow to have a pupil who’ll play Varèse. This is evolution. In any case, I think there has always been an element of provocation. And today it’s as necessary as ever. Who are the provocateurs today? Who are they? Where are the provocateurs?

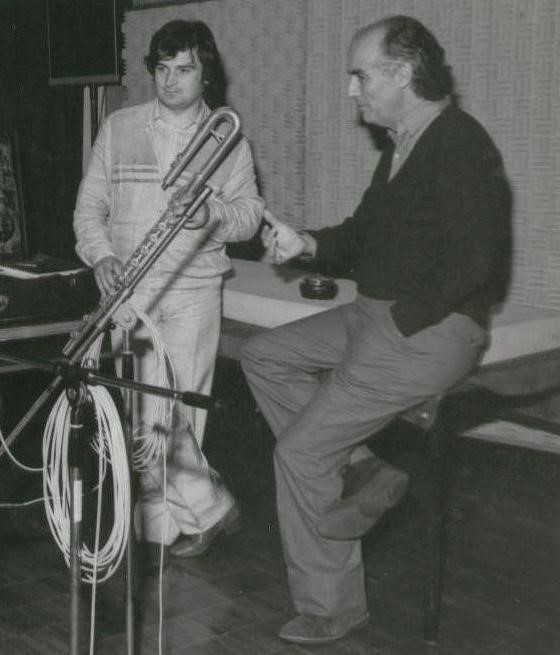

Figure 6 Luigi Nono and Roberto Fabbriciani, 1981. From the private collection of Roberto Fabbriciani

Nono described you through three different types of interpretations of the idea of provocation.

First, provocation through changing knowledge,

second, through continual comparison and

lastly through ‘the qualitative splendour of new dawns’.(Fabbriciani, ‘Walking with Gigi’)

These are strong descriptions, strong characteristics. Have they been of equal use for you, outside the close relation with Nono and his compositional project?

In fact, our relationship, beyond a deep understanding and friendship, was based on the idea of the infinite possibilities that thinking and art allow humans. An idea that has in its articulated premise a revolutionary attitude not merely limited to the aspects of composition.

Can these qualities be perceived as a problem or a challenge in any collaborations?

I do not think that they represent a problem, rather a ‘challenge’ to achieve ever higher and unknown goals.

Earlier, when we discussed different strategies for the performance of Nono’s late works, you described certain tendencies as being representatives of an academische Mentalität – could you explain what you mean by this?

I often hear performances of Nono’s later works that do not take into account his idea of sound and experimentation, that are addressed by performers with traditional academic performance practices. This will affect not only the idea but also the characteristics of sound found in the pieces composed by Gigi.

What would the opposite of academische Mentalität be?

The opposite is to work on the colour, the tone, the individual sound and not on the difficulty presented by the velocity of a piece. Nono did not write special effects to make people hear a collection of techniques. He selected with great care; few sounds, but many worlds.

In the article ‘Walking with Gigi’ you write:

He himself maintained that he did not wish to write definitive laws, which would lead to prescribed methods. He preferred a provocative approach with an openness towards an infinity of potential meanings, ignoring universally codified traditional techniques. The executant’s difficulty is clearly seen here, with the interpretation of his own aesthetics, by the extrapolation of a complex and heterogeneous meaning, from a simple and essential sign, which in turn must not result in a superficial or inaccurate interpretation, after all the executant is both singer and interpreter. This provocative approach was not so much a destabilising doctrine, but rather one to encourage introspection and deep thought. (Fabbriciani, ‘Walking with Gigi’)

This is a very interesting formulation. Could you expand on Nono’s use of provocation in his collaborations. How would he challenge you? Can you give an example where this provocative approach produced unexpected results (for both of you, perhaps)

Nono never presented you a score written in the solitude of an ivory tower, he wrote step by step, while the exchanges took place amongst us. It helped us collaborators to understand if what he had theorized could be viable, and where it might lead. It was a continuous exchange between us of knowledge and ideas.

At the outskirts of the work

Talking about provocations – Could you tell me more about Baab-Aar? We briefly talked about this earlier. How was that work developed? And why, in your opinion, is this no longer available from Ricordi?

Well Baab-Aar is a kind of special story. When Nono was ill, he called me: ‘Roberto, go to Berlin, play Baab-Aar again’. I played it for the second time in Berlin and Nono was very happy … he called me: ‘How was the performance?’ Fantastic, a huge success, I’m happy, I’m very happy … then when Nono died, his family and Ricordi talked to me, and this piece was no longer there.

The reason was that they claimed they had no score for this piece. Well, Ricordi had no score for many pieces. This piece was there, it existed but it was ‘impossible to play’, perhaps because of the issues with the Freiburg Studio, perhaps because Nono at the last minute chose not to use the electronic technique, but only instruments. Actually, Nono told me: ‘From now on, without electronic music, pause, p a u s e’. This was something new, we were to start working on a new project, the Manfred project. ‘Speak only with me for this project’, he said, and Baab-Aar was to be the first piece of this project.

The piece is structured around the movement of the performer throughout the concert hall, playing a single note, a b-flat. The intention was to achieve an ever-increasing rarefaction of writing, corresponding to an increased richness of meaning.

The premiere in Berlin in 1988 explored the spectrum of a single sound with its possible universes. The sound was ‘spatialized’ but without live electronics, using the large available range of emission techniques and the movements of the performer in the space. One of Nono’s goals was a more heightened and aware way of listening, aimed at savouring every little meaningful change, against any academic form. It was a beautiful experiment, wonderful.

Which emission techniques in specific are you referring to?

These are the new sound emission techniques which allow the spatialization of sound independent of live electronics.

Haller writes that the Berlin premiere of Baab-Aar included electronics. Was this the case? If so, was it only the second version of the piece (1989) that was done without electronics?

To produce the sound we had in mind the use of electronics was not necessary, and as it had been previously used for other purposes [A Eduardo Jabés], it did not help to create new sounds, they already existed acoustically.

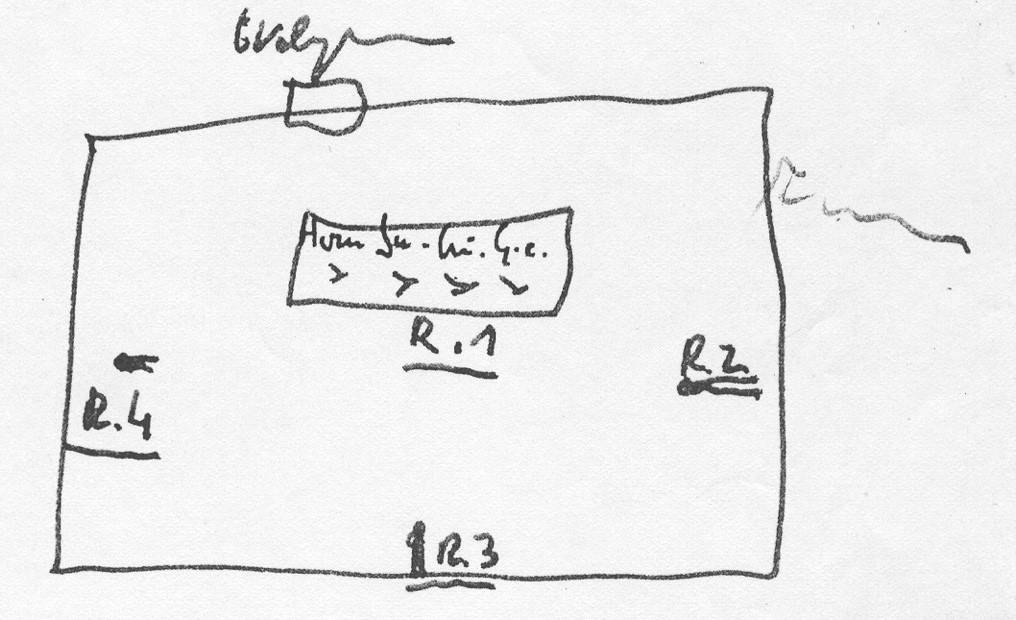

Figure 8 sketch for the diagram of the electronics used in A Eduard Jabes. Unpublished. From the private collection of Roberto Fabbriciani

Haller is quite categoric in refusing the idea of a publication of this piece. Why do think so?

This probably derives from the fact that the score remained on the level of a provisional draft. Between us, we had worked hard on the piece, it was sufficient, but for a publication you need to put some order to it.

You know, Baab-Aar is an old, old name, an old word, not a name, a personal name; it’s a word, a verb, a Venetian verb that means sciacolar, sciacolare. Not Italian, but Venetian: sciacolare means chatting, chattering, talking too much. But for Nono sciacolar is not to speak really fast, but very slowly. Gigi would speak every time very, very slowly, reflecting, thoughtfully, like Kurtág[26] – slowly, very slowly. Interesting, isn’t it? Gigi was like Kurtág when he spoke and Omaggio a Kurtág[27] originated as an imitation … with very few notes. It was a slow piece, rarefied, with pauses … like his personality. And so Baab-Aar is to speak, but a thoughtful way of speaking, very slowly–a note in all directions, but always different. Always focused on a single pitch. And this means also many, many possibilities for the music. Other composers have written for a single note, Scelsi of course, it’s nothing new, the single note. But for him … one note is its endless possibilities, a universe …

The following year, 1989, I performed the piece again, alone this time, on Nono’s request. But as early as in 1992, only two years after Nono’s death, the Committee for the Edition of Luigi Nono’s Works decided to forbid any new executions. The claimed that ‘a transcription derived from a registration would be an abuse, because it would not be reworked by Nono himself in the final draft. It follows therefore an impossibility to authorize new executions.’[28]

But this was the same for other pieces, all pieces at the time had an incomplete score. Very often, Nono only had the pillars, and I had the windows, the balconies. What I mean is that the building is something we made together, and the score is only later completed with all the material. Because the compositional process is like … ‘Roberto, I don’t like this, that one’s okay, no, play again’ and this is the compositional process. At the end the work is acceptable – how could I call it ‘final’? But in this kind of music, the word ‘final’ is very difficult to conceive of because every time you perform, change is inevitable. The space changes, everything changes.

So the composition and performance practice of Nono’s later works points towards a very open and empiric conception of musical work, of the listening act as well as the materialized sound. This hybrid practice can be challenging to document for the future, and also difficult to explain to historians or theorists who tend to focus on published scores and official work lists.

I agree, and it’s terrible for Nono, because … it’s like cutting down this table here, taking away a natural evolution of his music. I think a documented publication of the different materials would be necessary to preserve this part of his musical output.

A second round – the sound of Salvatore Sciarrino

Let’s move back to your experiences with Sciarrino. How would you describe the creation process of the first solo flute pieces, and how would this differ from your work with Nono?

My cooperation with Sciarrino started in the 1970s. I worked on all the pieces for solo flute belonging to the cycle Fabbrica degli incantesimi.[29] I’d make him listen to acoustic sounds, to materialized effects. I remember that we heard an owl while we were writing Hermes we find it in the middle of the piece, and the ‘hand’ of an alarm clock in Fra i testi dedicati alle nubi. With Nono, we would have different, sometimes even impossible, idealistic solutions, related to live electronics; slowly, with time, they became possible. This was a different approach. Both Sciarrino and Nono were open to new ways of listening and new qualities of sound, in their effort to change the musical language through different instrumental approaches. In Sciarrino’s music, the flute changes and renews itself through the acoustic sounds of everyday life, which are beyond our auditory attention. With Nono, the sonic change was more related to the use of amplification and live electronics.

My first Sciarrino premiere was All’aure in una lontananza[30] at Carnegie Hall in 1977,[31] at a concert dedicated to new music for solo flute.[32] Later I also premiered the version for solo bass flute. I remember that All’aure in una lontananza aroused great interest and curiosity from the beginning because it presented new ways of playing the flute. New possibilities such as harmonic trill, harmonic glissandos, whistle-tones, etc., were performed with three different kinds of flutes: in C, in G (contralto) and bass. The dynamics of the flute is such that it returns from nothing to nothing, reaching a pppp sound and in other cases air-only sforzato sounds. The harmonic trills create a surreal situation, a dimension where nothing seems defined. I think this piece has been very important for the flute and obviously for me.

Sciarrino is considered to have changed the way the flute is perceived in contemporary music. How do you see your own role in this process?

It was the result of a close cooperation. Sciarrino would use flute techniques and materials that I created – they were the product of my fancy, imagination and poetry. In the case of All’aure we met in Milano, where Sciarrino lived at the time, and also in Tuscany.

The performer’s role as co-creator is important in this music. In your experience, to what extent is this acknowledged by composers, publishers and the musical world in general?

Well, unfortunately the role of the performer-interpreter, often a co-author, is not recognized.

On his website, Sciarrino writes this about his sounds for flutes:

I would like to reflect on the meaning of having composed, in a few years, something that is no longer just a sequence of more or less successful works. It is a real corpus, and it means, first of all, that from now on the flute is no longer the same. And I do not expect to have disrupted it, but to have attracted it to an unknown corner of the world. I had invented most sounds more than twenty years ago; some recent ones have been provided by Fabbriciani; one, which had often recurred since 1971, belongs to Giancarlo Graverini. However, the same sounds that belonged to the common heritage of composers, today are also attributed to me with reason, because they finally seem conquered by the music. Each of my compositions is already in itself a legitimization of these sounds. The new sounds would be equivalent to a sophisticated cover on an old structure.

Once, we used to talk about ‘effects’. Here, structure and sound event arise from the same needs and grow or tend to a common vision, a new image. It is not a question of choosing more or less appropriate sounds, to embellish your home, but of ‘using new sounds to build new worlds’. This should be the aim of composers worthy of their name.

Do you agree with this description?

Yes, I do agree. Extraordinary compositions have been created with ‘some recent sounds provided by Fabbriciani’.

But this differs from what you told me earlier, that you ‘reinvented the flute’? Is there not a conflict of opinion here?

I have already expressed here what I mean. That Sciarrino was the first to use these new techniques for the flute is evident, as is the fact that I have provided, proposed and played them to him. There is no contradiction on these grounds.

When did your collaboration with Sciarrino end?

Our collaboration ended in 2000. After the first performance of Cerchio tagliato dei suoni.[33]

Why did you stop working together?

I would not know; I remember during our collaboration to have performed several works: Fabbrica degli incantesimi (L’Opera per flauto 1977–1989), La perfezione di uno spirito sottile, D’un faune per flauto e pianoforte, Addio case del vento per flauto solo (1993), La Divina Commedia di Dante Alighieri (1987), Musiche per il Paradiso di Dante, Frammento e adagio per flauto e orchestra (1986–1992) and others until Il cerchio tagliato dei suoni (1997).

Did your collaboration change over the course of this time? How?

Absolutely no.

Do you think the pieces you developed changed? Do you find that the ‘sonic project’ started with All’aure was completed? Were the whole line of pieces all true to the initial idea, in your opinion?

The recordings and notations that we did together clearly respect the sonic and compositional idea. Our work was very open – in Italian it’s gestazione – a process to develop something. All’aure in una lontanaza was the first piece, it was not written in a week, but … a much longer process over several months. Typically, the first thing would be that I’d improvise and play for him. For example, I’d hear a sound, e.g. with a special opening in the throat, then I’d notate an example and play again. Later this example would get developed in a score by Sciarrino. Again, it was a process. Following this, it was very easy for him to write this piece following this example. I wrote such-and-such fingering position will result in so-and-so pitch, e.g. In the text you showed me, Sciarrino wrote some recent sounds, but some is not specified. Is some 3 or 300? The term is relative. This some turned out to be whole works for flute. Sciarrino doesn’t specify which ones, but ‘some’ include tongue rams, whistle tones, hissing sounds, harmonics … everything that now is in the pieces.

You know, all these seven pieces are dedicated to me, except Canzone di ringraziamento which is dedicated to Petrassi, on my request. He was an important composer in Italy, and I performed it the first time in his presence. I thought it would be a good gesture, because I wanted him to continue working. I didn’t ask Sciarrino to dedicate the other pieces to me, our collaboration was more natural. I think his dedication was an act of friendship, for a friend. This is what working together means. And therefore, it is more important that one piece is dedicated to a great composer, because the work – the work is even more important than us. Art is above us as individuals.

Endnotes

[1] For an exhaustive list, see www.robertofabbriciani.it/ing.htm.

[2] May 2015 through April 2016.

[3] Fabbriciani has approved all quotations and translations, but any lack of clarity, errors of translation or other faults are the full responsibility of the author.

[4] Bruno Bartolozzi (1911–1980) was an Italian violinist and the author of several books on contemporary woodwind techniques.

[5] Bruno Maderna (1920–1973) was an Italian composer and conductor.

[6] This passage is close to formulations found in Roberto Fabbriciani, ‘Walking with Gigi’ Contemporary Music Review, 18/1 (1999), 7–15. http://doi.org/10.1080/07494469900640031.

[7] The transition of Nono’s compositional method towards an empiric approach is also described by Nono scholar Jürg Stenz, in his liner notes to Luigi Nono, A Pierre. Dell’azzurro silenzio, inquietum – …sofferte onde serene… Omaggio a György Kurtág – Con Luigi Dallapiccola. NEOS 11122, 2010.

[8] ‘These are virtuosos not only of the fingers but of the mind, not like a 19th-century idiot playing a narrow repertory.’ Quoted in Will Crutchfield, ‘Luciano Berio Speaks of Virtuosos and Strings’ New York Times, 13/1 (1989), 3.

[9] Severino Gazzeloni (1919–1992) was an Italian flutist.

[10] The hyperbass flute – or flauto iperbasso – is an instrument of Fabbriciani’s invention reaching four octaves below the concert flute, to a mere 16 hz.

[11] Sylvano Bussotti (1931–) is an Italian composer.

[12] Bruno Bartolozzi, New Sounds for Woodwind (London: Oxford University Press, 1967).

[13] Luigi Nono: Post-prae-ludium n. 3 ‘BAAB-ARR’ for solo piccolo solo and live electronics (withdrawn).

[14] An analytical tool that visualized frequency and amplitude information of a realtime sound signal.

[15] Prometeo: Tragedia dell’ascolto (1984).

[16] Sources at the Nono archive indicate that the period referenced is 1980/1981.

[17] The quotation ‘Caminantes, no hay caminos, hay que caminar’ (Wanderer, there is no road, only walking) is referenced in several of Nono’s later works.

[18] This concerns not only Das atmende Klarsein but also works such as Quando Stanno Morendo, Diario Polacco N. 2, Omaggio a György Kurtág and Risonanze erranti a Massimo Cacciari.

[19] This observation is supported by Michael Gorodecki, ‘Strands in 20th-Century Italian Music: 1. Luigi Nono: A History of Belief’, The Musical Times, 133, no. 1787 (Jan. 1992), 10–17, and Laura Zattra, Ian Burleigh and Friedemann Sallis, ‘Studying Luigi Nono’s A Pierre. Dell’azzurro silenzio, inquietum (1985) as a Performance Event’, Contemporary Music Review, 30/5 (2011), 411–39.

[20] Ciro Scarponi (1950–2006) was an Italian clarinettist and composer.

[21] Giancarlo Schiaffini (1942–) is an Italian trombonist, tuba player and composer.

[22] Giulio Briccialdi (1818–1881) was an Italian composer and flutist.

[23] Johann Joseph Ziegler (1795–1858) was a Viennese flute maker.

[24] Cecare Ciardi (1818–1877) was an Italian flutist and composer.

[25] Leonardo de Lorenzo (1875–1962) was an Italian flutist who emigrated to the USA.

[26] György Kurtág (1926–) is a Hungarian composer and pianist.

[27] Luigi Nono, Omaggio a György Kurtág, for contralto, flute, clarinet, bass tuba and live electronics, 1986.

[28] Quoted from the website of the Luigi Nono Foundation, www.luiginono.it.

[29] The cycle consists of a series of works for flute solo: All’aure in una lontananza; Hermes; Come vengono prodotti gli incantesimi?; Canzona di ringraziamento; Venere che le grazie la fioriscono; L’orizzonte luminoso di Aton and Fra i testi dedicati alle nubi.

[30] Version in C for solo flute.

[31] 21 July 1977.

[32] Works by Camillo Togni and Sylvano Bussotti.

[33] This is a work for four flute soloists and 100 mobile flutists, composed by Sciarrino in 1997, premiered on 26 July 1997 at Cividale del Friuli with Fabbriciani, Luisa Sello, Manuel Zurria and Mario Caroli as soloists.