Towards a Post-Percussive Practice

Table of contents

DOI: 10.32063/0204

Håkon Stene

Håkon Stene is a percussionist active both in artistic research and as a concert performer around the world. In 2014 he concluded the project This is Not a Drum at the Norwegian Academy of Music, where he is currently developing the project Music with the Real in collaboration with composer Henrik Hellstenius. www.hakonstene.net

by Håkon Stene

Music + Practice, Volume 2

Explorative

Representing the new breed of percussionists: Håkon Stene records Michael Pisaro’s Ricefall at Tomba Emmanuelle in Oslo, May 2011. (Photo: Frederic Boudin).

Though one of the oldest of the musical arts, percussion playing, especially within the Western classical tradition, has developed rapidly and been subject to significant change in the recent 60 to 80 years. The growing presence of percussion as a solo medium in classical music was primarily linked to avant-garde movements flourishing in the first decades of the twentieth century. Along with extra-musical objects such as household implements, and electronic devices such as radios, tape recorders and turntables, percussion emerged as a fresh medium for the expansion and alteration of Western music’s building blocks, perfectly suiting the period’s escalating quest to break new musical ground beyond the romantic tradition and mainstream conformism.

In this article we will look at tendencies emerging in the field of experimental music during the last ten years that continue the direction percussion music has taken since the mid twentieth century, but are not directly connected to percussive techniques or instruments. The compositions discussed here are not percussion works per se, since they do not necessarily involve percussion. However, percussionists, being accustomed to multidisciplinary practices through their repertoire of the past decades, perform these works and others of similar nature. Thus, we see the contours of a new, separate practice that I tentatively would like to label post-percussive – perhaps even post-instrumental.1)At this point it may be appropriate to separate this practice, based in traditional instrumental performance, from that of, say, the new breed of musicians using laptop computers and other electronic tools as their main instruments. It is equally important to acknowledge that there are non-percussionist performers in the field of New Music, such as pianists Mark Knoop, Stephane Ginsbourg and Sebastian Berweck who also operate within a similar field of mixed media and, cross-instrumental practices. But before we look at these examples, let us trace some of their history.

The first generation of works solely for percussion, composed by American avant-garde pioneers such as Henry Cowell, George Antheil, Edgard Varèse and John Cage, began to appear around 1930.2)More obscure, but equally interesting examples are the percussion music by Johanna Beyer (1888–1944), Harry Partch (1901–1974), William Russell (1905–1992), and Moondog (1916–1999), none of which, despite its originality, became part of the institutional canon or the catalogues of publishing houses. Altering European concepts of tempered pitch-harmony and tonal logic, their music was characterized by a focus on pulse and noise-based timbres, creating musical instruments of objects found in junkyards and elsewhere, or furthermore transforming existing instruments such as preparing and playing inside pianos.3)Objects used included steel bars, metal pipes, tin cans, washboard kit, sheet metal, firecrackers, brake drums, alarm bells and household objects such as suitcases, books and kettles. The introduction of found objects in musical settings makes an interesting and, I believe, not coincidental parallel to Marcel Duchamp’s concept introduced in the visual arts around 1913.4)Marcel Duchamp: Bicycle Wheel (1913) and Fountain (1917). Interestingly, Erik Satie’s Parade (1917), influenced by the Dada movement, included typewriter, sirens, splashing water, revolver, lottery wheel and glass bottles into a traditional ensemble; German Hans Jürgen von der Wense’s Musik für Klavier, Klarinette and freihängendes Blechsieb (Music for Piano, Clarinet and Suspended Kitchen Sieve) (1918) employed household implements; American William Russel’s compositions from the early 1930s used ‘found object drum kit’.

Another important influence for the vast expansion of acoustic material was the idea of electronic sound sculpting that started to take shape around this time. Compositions for acoustic instruments preceding electronic sound sources, notably by Varèse, opened up a field in which all sounds, noises and acoustic phenomena, as well as new spatial possibilities, became imaginable, and were transposed to acoustic instrumental music. Complexes of novel percussive colour thus offered an extensive contribution to this palette.5)For an excellent account of this, readers are advised to consult Jean Charles François’ Percussion et musique contemporain (Paris: Klincksieck esthétique, 1991).

The earliest music for solo percussion appeared in the 1950s with works such as 27’10.554” by John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Zyklus,6)Composed in 1956 and 1959 respectively, 27’10.554” was the first multi percussion solo, Zyklus the first European work of its kind. followed by Morton Feldman’s quiet reaction The King of Denmark (1963) and Helmut Lachenmann’s Intérieur I (1965–66). Early solo percussion writing was characterized by an abundance of instruments gathered in large batteries, brought to resonance by a limited set of techniques, namely that of striking. Later decades saw a reaction to this in works that explored a smaller instrumentation, but a broader array of sound producing actions. For the sake of a general overview it is possible to divide the body of classical percussion music into at least three categories:

- Works exploring timbre and resonance7)Such as in solo works by Cage (1956), Stockhausen (1959), Feldman (1964), Lachenmann (1966), Wuorinen (1966), Smith-Brindle (1967), Henze (1971), De Pablo (1973), Vivier (1980) Sciarrino (1986), Lucier (1988), Jarrell (1989), Eötwös (1993), Saariaho (1995) and Adams (2002).

- Pulse-based works8)Such as nearly all percussion works by Xenakis, Nørgaard (1967/1983), Alvarez (1984), Volans (1985), Wood (1986), Lang (1991), Wallin (1991), Ferneyhough (1991) and ensemble works by Cage, Reich etc.

- Music theater pieces9)Such as solo works by Kagel (1971/1995), Aperghis (1980/1982), Globokar (1973/1982/1989/1994/1997/2008), Rzewski (1985), Sarhan (2010), Appelbaum (2011) and Hoffmann (2001). The latter’s work An-Sprache explores an almost scientific percussive investigation of the body’s interior, continuing an idea introduced in Globoakar’s Corporel (1982) where the performer’s body is the one and only instrument.

This article presents three recent cases, among many, that I propose contribute to the formation of a fourth category, a category that I classify as percussion works only reluctantly. These are works that expand further the instrumental hybridism already inherent in Western percussive practices, transforming percussive and non-percussive sources alike into a mixed instrumental language. This tendency adds to the number of objects, playing techniques and concepts assimilated in our field, and highlights the rather special – and in classical music perhaps unparalleled – situation: that it has become possible to operate under the label ‘percussionist’ without performing any instrument traditionally regarded as percussion. Building on the fact that actions such as singing, scraping, talking, tearing, bowing and blowing are already integrated in experimental percussion, a new tendency is to transpose these modes of action on to instruments that are part of other established practices, thereby creating a performance practice in between or beyond defined instrumental categories. I propose the labelling Post-percussive Works.10)Other instrumental works suiting this category may include New Music classics such as Alvin Lucier’s Music for Performer (1965) and I am Sitting in a Room (1969); Giacinto Scelsi’s Ko-Tha (1967) for performer striking a guitar (or bass or 6-string cello); Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music (1968) for microphones and loudspeakers; Helmut Lachenmann’s Guero for piano (1970) and Pression for cello (1970); Maurizio Kagel’s Acustica (1970); Giorgio Battlistelli’s Jules Vernes (1987) for three performers; Manos Tsangaris’ Tafel I (1989) for two performers at a table; more recently Simon Steen-Andersen’’s Pretty Sound for piano (2008) and Black Box Music (2012); Alex Garsden’s Macrograph (2009); Carola Bauckholt’s Hirn & Ei (2010) for four wind jackets; Thomas Maedowcroft’s The Great Knot (2011) and Cradle (2012) for three performers; Simon Løffler’s b (2012) for effect pedals and fluorescent light; Trond Reinholdtsen’s Inferno (2013) for solo performer and video; Steffen Krebber’s Laufzeitumgebung (2013) for two performers; Erik Dæhlin’s Absence is the Only Real (2014) for solo performer controlling an entire installation – as well as those works mentioned in footnote 13.

General and work-specific techniques

Musical performance is a learned activity partly grounded in norms determined by style or genre. Accordingly, those norms influence what skills and which aspects of instrumental mastery musicians of various styles will acquire. Performing musicians possess their instrument-specific craft as well as skills covering common aspects of performance: skills associated with ensemble playing, communication and so forth (relating to musical pulse, timing, phrasing, etc.).

In classical music, especially in fields carrying long instrumental traditions for their canonical instruments, the way in which musicians approach their instrument is a highly evolved and defined practice, which is to say it is a practice that often precludes other ways of thinking. The way of approaching the instrument is relatively fixed, modified only gradually and passed down from master to pupil through generations. The instrument is likely to be regarded as a physical extension of the body, a channel for emotional and personal expression, and this relationship may be cultivated over a lifetime. Technique, no matter how difficult the music, is something that ideally should not come between interpreter and medium.11)Obviously, the idea of technical evolution and development is nothing new, and there are countless methods documenting this in history. However, the general physical actions involved in playing a string instrument or a keyboard have largely remained intact. Although concert pianists or organists constantly perform on different instruments in different halls and are required to re-adjust their technique accordingly, one traditionally relates to one kind of instrument only. This is not the case with percussion, and in this brief article I allow myself to draw general distinctions.

From a purely technical-mechanical standpoint, though, traditional Western pitch-based music is, in generalized terms, quite easy to circumscribe in terms of what range of skills is required to perform it; kinaesthetic mastery of scales, triads, arpeggios, chords and so forth constitute the range of technical requirements essential to most styles of music.12)Dynamic control, articulation and timbre should also be included. Since they serve expressive aspects of sound, I choose to categorize them apart from mechanical aspects in this context. In percussion playing, these elements, as well as the single stroke and the roll, traditionally constitute the technical requirements for most genres. Nevertheless, these basic technical skills are quite often not relevant or useful in experimental music. A pianist would gain little from practising arpeggios as preparation for a performance of inside-the-piano pieces such as Stefan Prins’ Etude Interieur (2004) or Simon Steen-Andersen’s Pretty Sound (2008). Similarly, standard guitar technique is of little significance in Lachenmann’s extended technique masterpiece for two guitars Salut für Caudwell (1977), as is the legato bowing in Lene Grenager’s The Operation (2011) for table-top cello.13)Stefan Prins (b. 1979), Etude interieure for inside piano and marbles (2004), http://www.stefanprins.be/eng/composesInstrument/comp_2004_01_etudeinterieur.html; Simon Steen-Andersen (b. 1976), Rerendered for amplified piano with two assistants (2004) and Pretty Sound for amplified piano (Edition S, 2008); Helmut Lachenmann (b. 1935), Salut für Caudwell for two speaking guitarists (Breitkopf & Härtel, 1977); Lene Grenager (b. 1969), The Operation for table-top cello and ensemble (Norwegian Music Information Centre, 2011).

Traditional technique does not necessarily aid one’s ability to play these pieces. The technical skills required by such compositions cannot be reduced to common, general exercises practised separately in order to support one’s fundamental ability to perform them. Their diversity and contextual specificity elude a reliable overall definition and application. Hence, we arrive at the concept of work-specific technical practices. The consequence for performers of such works proposed by my fourth category is that, in principle, there is no unifying technical legacy towards which they gravitate. Compared to classical music’s technical methods, these works signify a periphery without centre and may unfold themselves in the gaps between extended instrumental techniques, performance, theatre, installation or video art. Rather than being homogenous, they are multi-directional and thus constitute the need for continuous re-orientation on behalf of the practitioner.

Anyone involved in contemporary music knows the need for adaptability to heterogeneous settings. In particular, percussionists performing so-called multi-percussion set-ups, that is, collections of instruments varying from work to work, experience this constantly. The ability to recalibrate one’s technique and movement to these set-ups is among our craft’s most valuable and necessary skills. In avant-garde music traditions, composers and performers have deliberately challenged idiomatic ideals in search of new expressive means by transgressing technical conventions. Once these novel technical phenomena gain a performance tradition, they develop and improve in the hands of their practitioners and contribute to an ever-broader development of instrumental expressivity.

Three post-percussive works

In what follows, I describe three cases that exemplify radically different technical and instrumental characteristics.14)These case studies are by no means analytically exhaustive. Only general features relevant for performance are described. They do not belong to any established technical norm other than their own. What unifies them, in this case, is the fact that experimental percussionists embrace and perform such repertoire. Perhaps this is explained, in part, by the advantage we gain from being accustomed to performing on multiple instruments employing multiple, often unrelated technical grammars. Although percussionists mostly perform them, some of these examples are so remote from the origin of percussion and its traditional techniques that we may diagnose a mutation of an instrumental practice. Whilst proposing to label our fourth category ‘post-percussive works’, I will therefore argue that, at least technically, there should be no reason for these works or others of similar nature to be performed exclusively by percussionists. In fact, I am inclined to question whether any musical training is required in order to perform some of these works.15)This does certainly not apply to all works that could be defined as post-percussive, also not necessarily the ones presented in detail here, perhaps with the exception of Michael Piaro’s Ricefall. If general technical demands for post-percussive works are poorly specified, perhaps another tentative distinction needs to be drawn between practices whose technical grammar is defined through a coherent canonical repertoire, by coherent methods – for instance such as piano or flute methods – and those defined by each individual practitioner and his or her expertise. We cannot point to a set of coherent skills defined by the post-percussive repertoire itself. Rather, it suggests that one can define one’s own set of skills and shape the practice according to individual desire or according to what any given work may ask for.

If contemporary music in general requires a high degree of instrumental expertise and intellectual effort on behalf of the performer, the work Ricefall does not. In fact, it requires no instrumental skill at all. Inspired by a literary passage about the sound of rain, playing with the idea of composing a landscape in rain, Pisaro employs rice as a metaphor for rain.16)Previous examples of the acoustic sound of water in contemporary music are John Cage’s Water Music (1952) and Water Walk (1959), Nicolaus A. Huber’s Herbstfestival (1989), Caspar Johannes Walter’s Lichtwechsel (1993) and Tan Dun’s Water Concerto (1998), more obscurely in performance art through event-works of the Cage-influenced George Brecht. Beyond that, musical imagery of water is featured in ancient cultures through instruments such as the South American rain stick and more recent products such as ocean drum, waterphone and hydraulophone; in classical music through works by Chopin, Debussy and Ravel among others. Ricefall became Michael Pisaro’s first composition using the dropping technique – a manner of producing sound by means of dropping light objects onto resonators – a technique he developed further in works such as A Wave and Waves (2008). Pisaro writes:

At the end of a beautiful, detailed passage describing all of the minute sounds of the rain in his backyard, John M. Hull in his book Touching the Rock, writes: “The whole scene is much more differentiated than I have been able to describe, because everywhere are little breaks in the patterns, obstructions, projections, where some slight interruption or difference of texture or of echo gives an additional detail or dimension to the scene. Over the whole thing, like light falling upon a landscape, is the gentle background pattern gathered up into one continuous murmur of rain. I think the experience of opening the door on a rainy garden must be similar to that which a sighted person feels when opening the curtains and seeing the world outside. The rain presents the fullness of an entire situation all at once, not merely remembered, not in anticipation, but actually and now. If only rain could fall inside a room, it would help me to understand where things are in that room, to give a sense of being in the room, instead of sitting in a chair”.17)Pisaro, Ricefall (2004). Pisaro is quoting John M. Hull, Touching the Rock: An Experience of Blindness (London: SPCK, 1990).

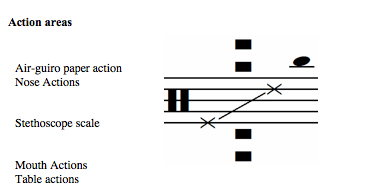

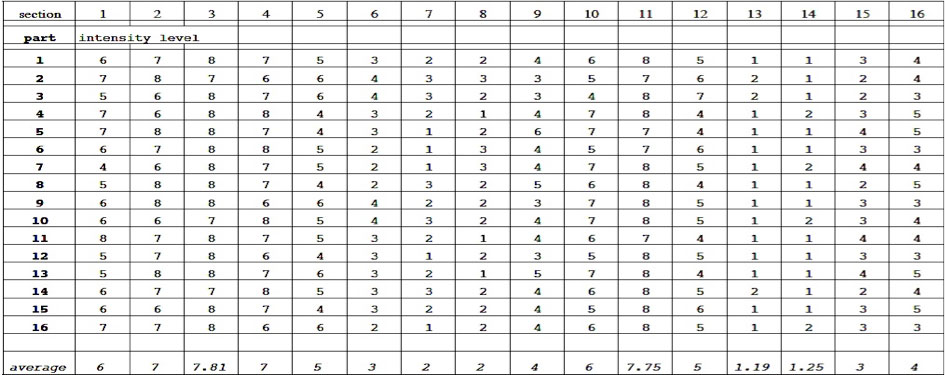

Written for 16 performers (it may also be performed by 2×16, 3×16 or 4×16 players) dripping rice onto undefined surface materials, the score suggests a variety of possible interpretations. The work is divided into 18 sections of 1-minute intervals. Except a silence at the very beginning and end, all players or parts remain active throughout the 16 minutes, and by prescribing each local density level (1 through 8 – 1 being a single grain every 2–3 seconds, 8 being a constant stream) – the global intensity is shaped. This form is stochastically calculated, invented and fixed (the average density being given in the lower row of Figure 1), but the resulting rhythmic microstructure takes on, just like rainstorms, endless varieties and shapes, the number of impulses at times getting so dense that it resembles white noise. Unlike rainstorms, however, unison changes in density occur steadily every minute, and within every section each performer continues a steady pace at the given intensity. Consequently, Ricefall alternates between sections of complex rhythmical play and massive noise.

Figure 1 Michael Pisaro: Ricefall, global chart. Reproduced with kind permission of the composer and Edition Wandelweiser.

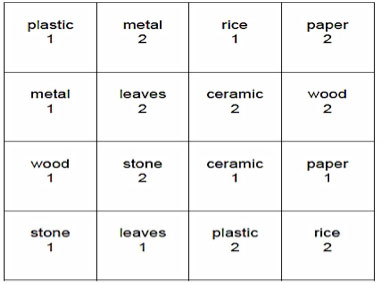

Pisaro suggests eight different sounding materials upon which rice falls (see Figure 3).

Figure 2 Michael Pisaro: Ricefall, spatial layout. Reproduced with kind permission of the composer and Edition Wandelweiser.

This layout creates a ‘sonorous topographic space’ in which the ear may orient itself. The only resemblance of percussive acts is the gravity making two bodies strike together, one or more times. In this manner Ricefall represents not a formal-structural chance music, as championed in the 1950s and ‘60s by Roman Haubenstock-Ramati, John Cage, Earle Brown, Christian Wolff and others, but a situation where each grain physically signifies a chance operation, in that there is a gap, an unknown factor, between the dripping and the bouncing, hence the rhythmical gesture created. Letting go of the touch – the minute, tactile control and Fingerspitzengefühl that otherwise characterizes musicianship – implies an interesting twist in instrumental technique in that it requires no skill. If there is a craft connected to dropping rice, it is accessible to anyone who cares to try. To perform Ricefall does not call for a sense of rhythm, pitch, dynamic or timbre. To my mind, some of the beauty of the work lies in this fact – nearly anyone could participate in its performance.18)This particular feature is shared with other works in the experimental tradition that draw inspiration from conceptual art or deliberately avoid the need for professional musical expertise. Examples are Cornelius Cardew’s The Great Learning (1968–71), which was composed for the Scratch Orchestra, a group consisting of musicians and non-musicians alike, experienced artists and people with no previous experience in the arts; Christian Wolff’s Prose Collection for various constellations (1969); Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Aus den sieben Tagen (1968) and Mathias Spahlinger’s Entlöschend for large tam-tam (1974). It does require, however, a certain amount of discipline as regards following the few instructions given. As with all ensemble playing, even this piece finds its balance between individual energy and group energy, and a successful performance implies precise sectional shifts and rice steadily streaming, not clustering, onto the ground. Pisaro’s control of the global aspects mean that performers are not given creative freedom to invent gestures, however, their responsibility is to drop rice within the prescribed eightfold density. These seemingly anti-artistic, insignificant little actions gathered as myriads of strokes detached from muscular control, produce an extraordinary soundscape saturated with percussive texture and liveliness.

In Her Frown was written for and premiered at the Royaumont festival in 2007. Originally scored for two sopranos and amplification, the work was transposed for two non-singing performers for the recorded version released in 2011, where Simon Steen-Andersen performs spoken actions and I, using multi-track recording, perform the rest.

Sound material

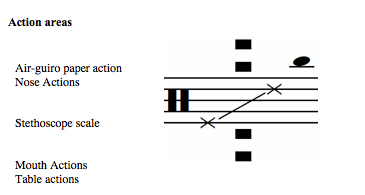

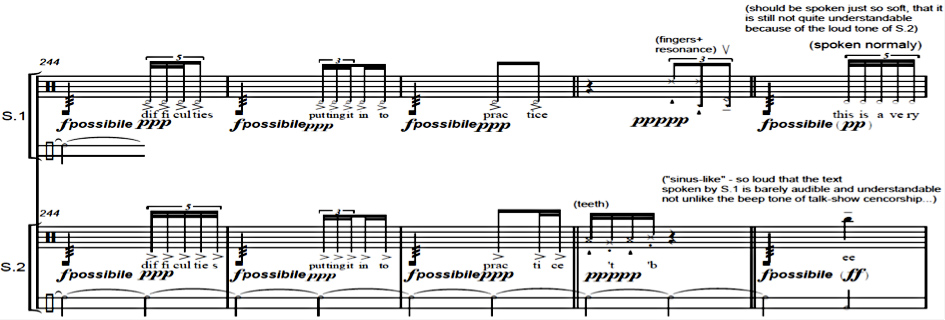

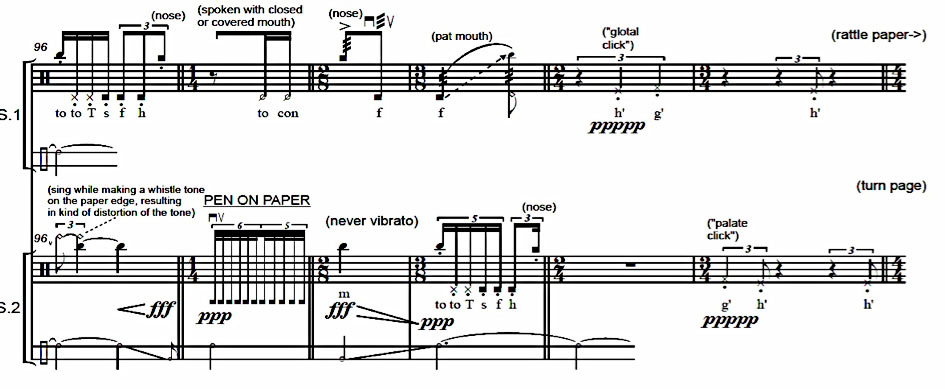

The work’s basic material explores rather simple actions such as blowing air on perforated paper, rattling and writing on paper, as well as talking and a variety of oral, percussive sounds. Sounds are divided into seven groups notated in five action areas as indicated in Figure 3:

1. Exploring sound colours in a piece of paper

1.1 Air-guiro: By perforating a piece of paper (DIN A4 size) and exhaling/inhaling through the holes with different types of pressure, at a different distance, at different speeds across the paper, an air-noise guiro is created. The entire opening of the piece is based on these actions. Dynamics: fff/ppp.

1.2 Rumble: Lightly shaking a large sheet of paper close to a microphone, producing a deep, rumbling drone. Dynamics: pppppp.

1.3. Ripping

2–3. Mouth and nose actions

- Articulating text without using vocal chords or air stream

- Articulating text with closed or ‘stopped’ mouth

- Hyperventilating

- Exhaling while patting the mouth

- Inhaling while covering mouth with fingers

- Rhythmically inhaling/exhaling

- Whistling, at times while patting the mouth

- Transitions between whistling, air sound and blowing

- Producing whistle tones by subtly blowing a focused air stream, humming or whistling at the edge of the air-guiro. Used in combination with mouth actions. Dynamics: ppp.

4. Stethoscope scale: A percussive scale of extremely quiet sounds moving from the bronchus towards mouth, teeth, fingers as well as clicking of nails. Dynamics: ppppp.

5. Table actions

- Rhythmicized writing. Dynamics: ppp

The entire range of sounds is in itself extremely soft, at times barely audible. The performers’ throats are therefore intimately ‘stethoscoped’ by microphones, exposing the micro-sounds of their insides. Extreme amplification is a central element in many of Steen-Andersen’s works and is often a fundamental musical factor in that it equalizes the gap between the audible and the inaudible, making the acoustically inaudible available as musical material. In his compositions there are often balanced counterpoints between unamplified loud sounds and amplified soft sounds, the amplifiers themselves sometimes taking on independent musical roles alongside the instruments. The procedure elaborates the concept of musique concréte instrumentale, introduced by Helmut Lachenmann. Here, instrumental noises traditionally regarded unworthy in the hierarchy of musical beauty – sounds of mechanics and bodily movement – are included as integral parts of the compositional material.

Another feature often displayed, also within In Her Frown, is the idea of a suppressed energy. Various techniques or filters are applied to charge physical resistance onto the performer’s body, for example expressed through precise instrumental choreography with weights attached to the limbs of the performers, or as a constant struggle for softer dynamics, causing the negative, conflicting movement to dominate, dynamically and visually, the actual audible outcome.

The text included in the piece is a combination of two dictionary entries – to communicate and to perceive – arranged in such a way that it resembles a poem. Commenting on the difficulties of communication, the words are ‘effortfully’ articulated by the performer. Again, there are compositional hindrances blurring them; articulating the words con bocca chiusa or without air, leaving only a forced miming as well as clicks and attacks from inside the mouth. The programme note thus becomes an extension of the work, articulating a friction between the statements about ‘clear communication’ and their obstructed performance.

In the new, transposed version the only sung material of the original – a high B natural – was replaced by a canned air horn, a choice that resonated with the idea of suppressed energy. Contained within a small can, this extremely loud and physically harmful sound serves a double function: a purely practical one, as well as that of covering the spoken text in the manner of a censor beep.19)Text of In Her Frown: To convey information about / make known / impart / communicated her views to the office / To reveal clearly / manifest / her disapproval communicated itself in her frown / To become aware of, know, or identify by the means of the senses / I perceived an object looming through the mist / To recognize, discern, envision, or understand / I perceive a note of sarcasm in your voice / This is a very nice idea, but I perceive difficulties putting it into practice. www.dictionary.com, communicate/perceive

Figure 5 Simon Steen-Andersen: In Her Frown, bars 244–8. The excerpt illustrates table actions, muted text, stethoscope scale, censor tone. Reproduced with kind permission of the composer and Edition S.

The five action areas represent different musical material, which is directly connected to the various possibilities with the objects at hand. Separate sections of music are interrupted by new sequences, first as short fragments, then increasingly longer until a new continuity is established. Steen-Andersen refers to this interpolative construction as a multi-directional pseudo-polyphonic form, that is, a formal strategy whereby rapidly zapping between sequences allows many developmental levels simultaneously.

Figure 6 Simon Steen-Andersen: In Her Frown, bars 96–101. The excerpt shows four interrupted material developments. Used with permission of the composer and Edition S.

The highly sparse apparatus employed in In Her Frown presents technical and musical challenges that might seem unusual to any singer or instrumentalist. And for me as a percussionist, being accustomed to relating to instruments as external physical objects to be struck or excited by other means, the sonic production in this piece requires muscular control on a microscopic and partly inner level. In addition, sounds are extremely fragile and often occur in combination with physical obstructions. When adapting to this challenge, I benefited from a strong connection with bodily gesture acquired from my percussion playing. Though the means by which sounds are produced may be unusual – hybrids between miniaturized vocal and percussive techniques – the musical text itself demands what percussionists are trained for, namely rhythmical precision and clarity.

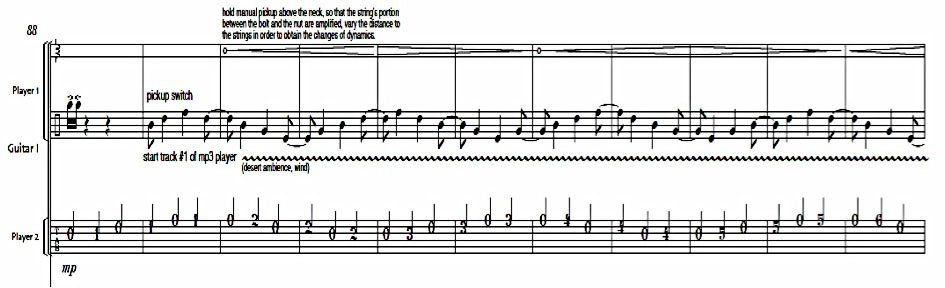

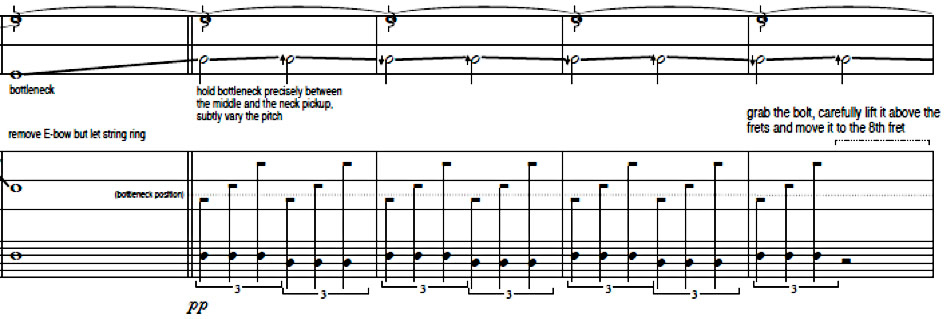

The idea of transformed percussive practices is highly evident in Black Horizon. Commissioned by a percussion group, Schlagquartett Köln, but scored for two table-top electric guitars, the piece explores a distinctly original and unconventional approach to instrumental playing whether one sees it from a percussionist’s or a guitarist’s perspective. As with Ricefall and In Her Frown, this work resists categorization, and in theory it could be performed by any schooled musician. The work combines traditional guitar techniques such as strumming, arpeggios and plucking, with more unique approaches using hand-held pick-ups, miniature playback systems with field recordings filtered through the pick-up switches, E-bows, bolts, slides and brushes.20)The E-bow is an electromagnetic, battery driven device that can sustain string resonance. Furthermore, each instrument is shared between two players sitting on opposite sides. A preparation known as ‘third-bridge-technique’ is applied throughout the piece, that is, a bolt positioned between the string and fretboard, allowing different actions to be played on both sides of the divided strings without interfering with each other. Playing the part of the string between this bolt and the bridge of the guitar generates resonances on the part of the string between the bolt and the nut and vice versa. These subtle harmonic phenomena are made audible by the hand-held pick-ups. Further, field recordings of desert winds and footsteps made in Death Valley and Anza Borrego in Southern California as well as film soundtrack samples are filtered through various pick-up combinations causing a registration colouring.21)Also, the following scordatura is used: Low E-string: unaltered; A-string: 2 cents lower than tempered; D-string: 31 cents lower than tempered; G-string: 33 cents lower than tempered; B-string: 64 cents lower than tempered; E-string: 66 cents lower than tempered. This chord structure is kept throughout, brought to resonance by traditional strumming, brushing or arpeggios, however steadily modulated by sliding the third-bridge bolt between frets.

Figure 7 Marko Ciciliani: Black Horizon, player 1, bars 88-98. The excerpt shows hand held pick-up amplifying string resonance whilst filtering field recording. Reproduced with kind permission of the composer.

Occasionally, a metal slide is used to create additional divisions of the string, allowing as many as three simultaneously sustained pitches per string (Figure 8)

Figure 8 Marko Ciciliani: Black Horizon, guitar 1, bars 533–555. The excerpt shows string ringing between bridge and bottleneck, bottleneck and bolt, bolt and nut. Reproduced with kind permission of the composer.

Figure 9 Marko Ciciliani: Black Horizon, bars 533–555. Field recording filtered through manual, pick-ups counterpointing plucked strings.

Black Horizon boasts oddly beautiful sequences with melodic and harmonic elements reminiscent of psychedelic music. It is an excellent example of how inventive and unconventional approaches to instrumental technique may uncover rich musical potential in ways we would not expect. It contributes to a development in which not only the diversity of percussive material is more complex and surprising than ever, but also the way in which materials are musically employed expands in novel directions.

New music – new tools

Despite the rather unusual apparatus employed in recent works such as Black Horizon, there is a long tradition of incorporating live electronic elements in percussion settings. Composers such as John Cage included radios and record players in Credo in US and the Imaginary Landscape series already in the late 1930s and 1940s. Karlheinz Stockhausen famously employed directional microphones and frequency filters as instruments alongside a tam-tam excited with various implements in his Mikrophonie (1964). Helmut Lachenmann’s concerto Air (1968) for percussionist and large orchestra included both a single string ektara and a table-top electric guitar.22)The ektara is a traditional instrument mostly used in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The instrumental setup for Air was created by American percussionist Michael W. Ranta, for whom the piece was written. Moreover, amplification and electronics in combination with acoustic instruments have been broadly experimented with throughout the history of experimental and avant-garde music; and through the low-cost accessibility and consumer-friendly technology following the digital revolution, these media have become standard ingredients in the set-ups of many percussionists, guitarists, keyboardists and other cross-media instrumentalists.

Music for Musician

The evolutionary tree of percussion roots back to the beginnings of human culture, branching out to all parts of the world. A very young branch on that evolutionary tree is thus the musical avant-garde. On this branch, a rather unique Western phenomenon strongly connected to the concepts of modernity influenced the liberation of traditional hierarchies, experimentation and the idea of material progress. The New Music movement historically defined itself by the principle of innovation and extension: By extending techniques and materials, it reached for ‘nie erhörte Klänge’ (‘sounds previously unheard’).23)This phrase was famously attributed to Karlheinz Stockhausen in the 1950s, although composers had embraced this aim as early as the 1920s. Important examples include Pierre Schaeffer’s Musique Concréte and the Fluxus movement. Extended compositional techniques, playing techniques, tonal modes, New sound sources and so forth, were elements that forced shifts in musical development throughout its history. They were achieved, at least in part, by another concept characterizing modernity, namely that of rationalization and categorization of musical parameters and materials, following a nearly scientific approach.24)For good summaries of the movement see (in English) Paul Griffiths, Modern Music and After (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), (in German) Ulrich Dibelius, Moderne Musik nach 1945 (Munich: Piper, 1998), or (in Norwegian) Dag Østerberg, Det Moderne: et essay om vestens kultur 1740-2000 (Oslo: Gyldendal, 1999).

In the same vein, our percussive practices have also radically altered its tools and techniques in search of new expressive vocabulary: from historical models of kettledrummers, to multi-tasking orchestral percussionists in the late romantic orchestra that saw a gradual expansion of instruments employed, followed by the expansion of playing techniques in the twentieth century. In the percussion sections of orchestras, composers began to ask percussionists to perform auxiliary tasks adding a variety of noises and colours to an otherwise fixed line-up. This situation remains largely the same in orchestras today: a string player is not likely to perform a part for musical saw, a flutist not likely to accept a part including anything else than flute, say glissando-flute. These tasks are assigned to the percussion section. This might be due to the low status that noisemakers hold in the traditional hierarchy of fine musical arts due to their primitive nature and the low degree of technical competence needed by the practitioners of many of these instruments.

Interestingly, in search of new musical colour, Western art music borrowed percussion instruments from all over the world. By altering their context and manner of operation, we created our own percussive language with these new tools. Perhaps owing to the sheer excess of materials borrowed, this adoption was often done in the name of simplification, utilizing only fragments of their original vocabulary, although the Eurocentric artists who first employed these foreign tools regarded their work as refinement of primitive noises.25)Observe, for instance, how playing techniques for castanets, tamburello, riq, pandeiro, maraccas, bongos and congas are played in their original context and how they are adopted to Western classical music settings. Louis Adolphe Coerne, in The Evolution of Modern Orchestration (1908) states (cited in Bugg (2003), p. 22): ‘Sound-producing apparatus devoid of definite pitch belongs to the initial attempts of primitive men to assist vocal expression of emotional feeling, to accompany religious orgies, or to encourage their warriors on the march. The modern orchestra includes the best of these primitive species, transformed into perfected types of genuine artistic value, and has also drawn into requisition various instruments originating in countries that are far apart. Most commonly used are the bass drum, the cymbals and the triangle. … Their mission is primarily to suggest “local” coloring or to emphasize rhythm for dancing’. A side effect of this practice was that the practitioners of this language became well-rounded polyglots who, in the wake of tonal dissolution midway into the twentieth century, used their hybrid skills to develop new technical-musical grammar motivated by the number of sounds and instruments available. Hence, this legacy has proved to be an advantage to our field, especially within the domain of experimental arts. The multi-tasking performer is more prepared, more apt to meet new and unconventional demands than are musicians relating exclusively and hermetically to one type of practice.

In addition to providing dramatic and rhythmic effect, percussion signified for the classic and romantic orchestral composer exoticism and foreign musical cultures.26)Notably to Turkish janissary music, the Arab world and the Far East. See Bugg (2003). As these exotic sounds slowly became standardized in Western contexts, new ones were included until the point where the accessorizing sound itself came to the foreground of music. Why the inclusion of noise? The answer John Cage and his contemporaries – clearly inspired by Dadaists and Futurists – asked this question and it still resonates today. Beyond the obvious wish to broaden the scope of musical colour through instrumentation, an underlying, more important driving force – perhaps parallel to the conceptual turn in the fine arts and its notion of an expanded field – may have been the desire to disturb and destabilize the hermetic distinction between art and real life. By playfully integrating and re-contextualizing the sonic elements of everyday life itself into musical works, they found an integral method of emphasizing this connection. This leads us to the current situation: scattered appearances of non-musical implements in concert music starting some hundred years ago, indicated that expansions in the percussive realm, beyond pure dramatic effect, had the potential to influence a new, autonomous genre and a new breed of performers who were to become natives of a novel practice operating apart from traditional instrumental performance. Many recent expressions of this potential have affected an evolution that has now led to a disconnection, in linguistic or biological terms, a mutation, where the fundamental characteristics of drumming are hardly recognizable any longer. It might be argued that this radical shift in Western art music is not likely to be found in other musical cultures precisely because it is motivated by a European idea of material expansion.

As a performer within the experimental field presented here, I constantly have to adapt to techniques and instrumentations developed specifically for a given work. I am furthermore confronted with fundamental questions regarding how to define the required skill set and, indeed, the level of virtuosity and perfection expected from classical musicians today. For the professional expert performer, instrumental expertise is developed through years of intense and intimate relationship with one’s instrument. However, if one chooses to embrace the variety and complexity of a post-percussive strategy as an open concept, one faces the risk of losing a coherent technical foundation and familiarity with one’s instrument, since every new work employs different tools. This is true whether one has to deal with new instruments or novel instrumental techniques. That musician – being a nomadic gatherer – belongs in principle to no defined practice: the practice of a nomadic gatherer becomes an attitude directed towards re-thinking and invention, illuminating the paradoxical situation that the only specialization and expertise left to us, is that of being specialized in being non-specialized. The conglomerate that constitutes that musical array has become a cultural and expressive melting pot that has shaped facets of modern music and will keep adding flavour to the future development of experimental musical arts.

Appendix

Chronological list of percussion works mentioned (lists are not complete):

1956: Cage, John: 27’10.554”, Peters Edition.

1959: Stockhausen, Karlheiz: Zyklus. Universal Edition.

1964: Feldman, Morton: King of Denmark. Peters Edition.

1966: Lachenmann, Helmut: Intérieur I. Edition Modern.

1966: Wuorinen Charles: Janissary Music. Peters Edition.

1967: Smith Brindle, Reginald: Orion M42. Peters Edition.

1967: Nørgård, Per: Waves. Edition Wilhelm Hansen.

1971: Henze, Hans Werner: Prison Song. Schott Music.

1971: Kagel, Mauricio: Exotica. Universal Edition.

1973: Globokar, Vinko: Toucher. Edition Peters.

1973: Pablo, Luis de: Le prie-dieu sur la terrasse. Suvini Zerboni.

1975: Xenakis, Iannis: Psappha. Edition Salabert.

1978: Aperghis, Georges: Le Corps à Corps. Editions Salabert.

1980: Vivier, Claude: Cinq Chansons pour Percussion. Boosey& Hawkes.

1980: Aperghis, Georges: Grafitti. Edition Salabert.

1982: Globokar, Vinko: ?Corporel. Peters Edition.

1982: Zimmermann, Walter: Glockenspiel. Beginner Press.

1983: Nørgård, Per: I Ching. Edition Wilhelm Hansen.

1984: Alvarez, Javier: Temazcal. Black Dog Editions.

1985: Rzewski, Frederic: To the Earth. Sound Pool Music.

1985: Volans, Kevin: She Who Sleeps with a Small Blanket. Chester Music.

1986: Sciarrino, Salvatore: appendice al perfeccione. Ricordi.

1986: Wood, James: Rogosanti. James Wood Edition.

1988: Lucier, Alvin: Silver Streetcar for the Orchestra. Material Press.

1989: Xenakis, Iannis: Rebonds. Edition Salabert

1989: Globokar, Vinko: Ombre. Ricordi.

1991: Lang, David: The Anvil Chorus. Red Poppy.

1991: Wallin, Rolf: Stonewave. Chester Music.

1991: Ferneyhough, Brian: Bone Alphabet. Peters Edition.

1992: Jarrell, Michael: Assonance VII. Editions Henry Lemoine.

1993: Eötwös, Peter: Psalm 151. Ricordi

1994: Globokar, Vinko: Dialog über Erde. Ricordi.

1995: Saariaho, Kaija: Six Japanese Gardens. Chester Music

1995: Kagel, Mauricio: L’Art Bruit. Edition Peters.

1995: Wolff, Christian: Percussionist Songs, Edition Peters.

1995: Reynholds, Roger: Watershed. Edition Peters.

1997: Globokar, Vinko: Pensée écartelée. Ricordi.

2001: Hoffmann, Robin: An-Sprache. Peters Edition.

2002: Adams, John Luther: The Mathematics of Resonant Bodies. Taiga Press.

2008: Globokar, Vinko: Au-delà d’une étude pour percussion. Ricordi.

2010: Sarhan, François: Home Work. Private edition.

2011: Appelbaum, Mark: Aphasia. Private edition.

Percussion Ensemble Works

:

1923/24: Antheil, George: Ballet Méchanique. Templeton Publishing.

1930: Roldán, Amadeo: Rítmicas 5&6.

1931: Varése, Edgard: Ionisation. Boosey& Hawkes.

1932: William Russel: Fugue. New Music Edition.

1933: William Russel: Three Dance Movements. New Music Edition.

1933: Beyer, Johanna: Percussion Suite in Three Movements. Unpublished manuscript.

1934: Cowell, Henry: Ostinato Pianissimo. Theodore Presser Company

1935: Beyer, Johanna: Auto Accident. Unpublished manuscript

1935: Cage, John: Quartet. Edition Peters.

1936: Cage, John: Trio. Edition Peters.

1939: Cage, John: First Construction (in Metal). Edition Peters.

1939: Cowell, Henry: Pulse. Theodore Presser Company

1940: Cage, John: Second Construction. Edition Peters.

1940: Cage John: Living Room Music. Edition Peters.

1941: Cage, John: Third Construction. Edition Peters.

1941: Harrison, Lou: Fugue. HBP

1942: Chavez, Carlos: Toccata. Alfred Publishing.

1943: Cage, John: Amores. Edition Peters.

1964: Stockhausen, Karlheiz: Mikrophonie I. Universal Edition.

1965: Kagel, Mauricio: Pas de cinq for 5 percussionists. Universal Edition

1969: Xenakis, Iannis: Persephassa. Edition Salabert.

1971: Reich, Steve: Drumming. Boosey & Hawkes.

1975: Stockhausen, Karlheiz: Musik im Bauch. Stockhausen Verlag.

1976: Cage, John: Branches. Edition Peters.

1976: Xenakis, Iannis: Pleiades. Edition Salabert.

1977: Kagel, Mauricio: Dressur. Universal Edition.

1988: Wood, James: Stoicheia. James Wood Edition.

1988: Huber, Nicolaus A: Herbstfestival. Berenreiter Verlag.

1989: Xenakis, Iannis: Okho. Editions Salabert.

1990: Grisey, Gérard – Le Noir de l’Etoile. Ricordi.

1991: Wallin, Rolf: Stonewave. Chester Music.

1994: Globokar, Vinko: Kvadrat, for four percussionists. Ricordi.

1997: Adams, John Luther: Strange and Sacred Noise. Taiga Press.

2006: Lim, Liza: City of Falling Angels. Ricordi.

2007: Hauser, Fritz: Bricco Lu. www.fritzhauser.ch

2010: Bauckholt, Carola: Hirn & Ei. Thuermchen Verlag.

2011: Meadowcroft, Thomas: The Great Knot. www.thomasmeadowcroft.com

2013: Meadowcroft, Thomas: Cradle. www.thomasmeadowcroft.com

Footnotes

References

| ↑1 | At this point it may be appropriate to separate this practice, based in traditional instrumental performance, from that of, say, the new breed of musicians using laptop computers and other electronic tools as their main instruments. It is equally important to acknowledge that there are non-percussionist performers in the field of New Music, such as pianists Mark Knoop, Stephane Ginsbourg and Sebastian Berweck who also operate within a similar field of mixed media and, cross-instrumental practices. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | More obscure, but equally interesting examples are the percussion music by Johanna Beyer (1888–1944), Harry Partch (1901–1974), William Russell (1905–1992), and Moondog (1916–1999), none of which, despite its originality, became part of the institutional canon or the catalogues of publishing houses. |

| ↑3 | Objects used included steel bars, metal pipes, tin cans, washboard kit, sheet metal, firecrackers, brake drums, alarm bells and household objects such as suitcases, books and kettles. |

| ↑4 | Marcel Duchamp: Bicycle Wheel (1913) and Fountain (1917). Interestingly, Erik Satie’s Parade (1917), influenced by the Dada movement, included typewriter, sirens, splashing water, revolver, lottery wheel and glass bottles into a traditional ensemble; German Hans Jürgen von der Wense’s Musik für Klavier, Klarinette and freihängendes Blechsieb (Music for Piano, Clarinet and Suspended Kitchen Sieve) (1918) employed household implements; American William Russel’s compositions from the early 1930s used ‘found object drum kit’. |

| ↑5 | For an excellent account of this, readers are advised to consult Jean Charles François’ Percussion et musique contemporain (Paris: Klincksieck esthétique, 1991). |

| ↑6 | Composed in 1956 and 1959 respectively, 27’10.554” was the first multi percussion solo, Zyklus the first European work of its kind. |

| ↑7 | Such as in solo works by Cage (1956), Stockhausen (1959), Feldman (1964), Lachenmann (1966), Wuorinen (1966), Smith-Brindle (1967), Henze (1971), De Pablo (1973), Vivier (1980) Sciarrino (1986), Lucier (1988), Jarrell (1989), Eötwös (1993), Saariaho (1995) and Adams (2002). |

| ↑8 | Such as nearly all percussion works by Xenakis, Nørgaard (1967/1983), Alvarez (1984), Volans (1985), Wood (1986), Lang (1991), Wallin (1991), Ferneyhough (1991) and ensemble works by Cage, Reich etc. |

| ↑9 | Such as solo works by Kagel (1971/1995), Aperghis (1980/1982), Globokar (1973/1982/1989/1994/1997/2008), Rzewski (1985), Sarhan (2010), Appelbaum (2011) and Hoffmann (2001). The latter’s work An-Sprache explores an almost scientific percussive investigation of the body’s interior, continuing an idea introduced in Globoakar’s Corporel (1982) where the performer’s body is the one and only instrument. |

| ↑10 | Other instrumental works suiting this category may include New Music classics such as Alvin Lucier’s Music for Performer (1965) and I am Sitting in a Room (1969); Giacinto Scelsi’s Ko-Tha (1967) for performer striking a guitar (or bass or 6-string cello); Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music (1968) for microphones and loudspeakers; Helmut Lachenmann’s Guero for piano (1970) and Pression for cello (1970); Maurizio Kagel’s Acustica (1970); Giorgio Battlistelli’s Jules Vernes (1987) for three performers; Manos Tsangaris’ Tafel I (1989) for two performers at a table; more recently Simon Steen-Andersen’’s Pretty Sound for piano (2008) and Black Box Music (2012); Alex Garsden’s Macrograph (2009); Carola Bauckholt’s Hirn & Ei (2010) for four wind jackets; Thomas Maedowcroft’s The Great Knot (2011) and Cradle (2012) for three performers; Simon Løffler’s b (2012) for effect pedals and fluorescent light; Trond Reinholdtsen’s Inferno (2013) for solo performer and video; Steffen Krebber’s Laufzeitumgebung (2013) for two performers; Erik Dæhlin’s Absence is the Only Real (2014) for solo performer controlling an entire installation – as well as those works mentioned in footnote 13. |

| ↑11 | Obviously, the idea of technical evolution and development is nothing new, and there are countless methods documenting this in history. However, the general physical actions involved in playing a string instrument or a keyboard have largely remained intact. Although concert pianists or organists constantly perform on different instruments in different halls and are required to re-adjust their technique accordingly, one traditionally relates to one kind of instrument only. This is not the case with percussion, and in this brief article I allow myself to draw general distinctions. |

| ↑12 | Dynamic control, articulation and timbre should also be included. Since they serve expressive aspects of sound, I choose to categorize them apart from mechanical aspects in this context. |

| ↑13 | Stefan Prins (b. 1979), Etude interieure for inside piano and marbles (2004), http://www.stefanprins.be/eng/composesInstrument/comp_2004_01_etudeinterieur.html; Simon Steen-Andersen (b. 1976), Rerendered for amplified piano with two assistants (2004) and Pretty Sound for amplified piano (Edition S, 2008); Helmut Lachenmann (b. 1935), Salut für Caudwell for two speaking guitarists (Breitkopf & Härtel, 1977); Lene Grenager (b. 1969), The Operation for table-top cello and ensemble (Norwegian Music Information Centre, 2011). |

| ↑14 | These case studies are by no means analytically exhaustive. Only general features relevant for performance are described. |

| ↑15 | This does certainly not apply to all works that could be defined as post-percussive, also not necessarily the ones presented in detail here, perhaps with the exception of Michael Piaro’s Ricefall. |

| ↑16 | Previous examples of the acoustic sound of water in contemporary music are John Cage’s Water Music (1952) and Water Walk (1959), Nicolaus A. Huber’s Herbstfestival (1989), Caspar Johannes Walter’s Lichtwechsel (1993) and Tan Dun’s Water Concerto (1998), more obscurely in performance art through event-works of the Cage-influenced George Brecht. Beyond that, musical imagery of water is featured in ancient cultures through instruments such as the South American rain stick and more recent products such as ocean drum, waterphone and hydraulophone; in classical music through works by Chopin, Debussy and Ravel among others. |

| ↑17 | Pisaro, Ricefall (2004). Pisaro is quoting John M. Hull, Touching the Rock: An Experience of Blindness (London: SPCK, 1990). |

| ↑18 | This particular feature is shared with other works in the experimental tradition that draw inspiration from conceptual art or deliberately avoid the need for professional musical expertise. Examples are Cornelius Cardew’s The Great Learning (1968–71), which was composed for the Scratch Orchestra, a group consisting of musicians and non-musicians alike, experienced artists and people with no previous experience in the arts; Christian Wolff’s Prose Collection for various constellations (1969); Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Aus den sieben Tagen (1968) and Mathias Spahlinger’s Entlöschend for large tam-tam (1974). |

| ↑19 | Text of In Her Frown: To convey information about / make known / impart / communicated her views to the office / To reveal clearly / manifest / her disapproval communicated itself in her frown / To become aware of, know, or identify by the means of the senses / I perceived an object looming through the mist / To recognize, discern, envision, or understand / I perceive a note of sarcasm in your voice / This is a very nice idea, but I perceive difficulties putting it into practice. www.dictionary.com, communicate/perceive |

| ↑20 | The E-bow is an electromagnetic, battery driven device that can sustain string resonance. |

| ↑21 | Also, the following scordatura is used: Low E-string: unaltered; A-string: 2 cents lower than tempered; D-string: 31 cents lower than tempered; G-string: 33 cents lower than tempered; B-string: 64 cents lower than tempered; E-string: 66 cents lower than tempered. This chord structure is kept throughout, brought to resonance by traditional strumming, brushing or arpeggios, however steadily modulated by sliding the third-bridge bolt between frets. |

| ↑22 | The ektara is a traditional instrument mostly used in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The instrumental setup for Air was created by American percussionist Michael W. Ranta, for whom the piece was written. |

| ↑23 | This phrase was famously attributed to Karlheinz Stockhausen in the 1950s, although composers had embraced this aim as early as the 1920s. Important examples include Pierre Schaeffer’s Musique Concréte and the Fluxus movement. |

| ↑24 | For good summaries of the movement see (in English) Paul Griffiths, Modern Music and After (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), (in German) Ulrich Dibelius, Moderne Musik nach 1945 (Munich: Piper, 1998), or (in Norwegian) Dag Østerberg, Det Moderne: et essay om vestens kultur 1740-2000 (Oslo: Gyldendal, 1999). |

| ↑25 | Observe, for instance, how playing techniques for castanets, tamburello, riq, pandeiro, maraccas, bongos and congas are played in their original context and how they are adopted to Western classical music settings. Louis Adolphe Coerne, in The Evolution of Modern Orchestration (1908) states (cited in Bugg (2003), p. 22): ‘Sound-producing apparatus devoid of definite pitch belongs to the initial attempts of primitive men to assist vocal expression of emotional feeling, to accompany religious orgies, or to encourage their warriors on the march. The modern orchestra includes the best of these primitive species, transformed into perfected types of genuine artistic value, and has also drawn into requisition various instruments originating in countries that are far apart. Most commonly used are the bass drum, the cymbals and the triangle. … Their mission is primarily to suggest “local” coloring or to emphasize rhythm for dancing’. |

| ↑26 | Notably to Turkish janissary music, the Arab world and the Far East. See Bugg (2003). |