Notre Dame Organum Duplum:

What Does a Performer Need from a Modern Edition?

Table of contents

DOI: 10.32063/0109

Penelope Turner

Penelope Turner trained as a singer in Cambridge (UK) and Tilburg (NL) and works from Brussels as a soloist and in small ensembles, specializing in early and contemporary music, both with her own groups — Ut Sol and X-Ambitus — and in collaboration with others.

by Penelope Turner

Music + Practice, Volume 1

Reviews + Commentaries

For years, musicians wishing to perform organum duplum1)Organum duplum is two-part polyphony that sets the solo sections of responsorial chants from the Offices and the Mass for performance on important feast days. For further explanation and definitions of related terms, seewww.penelopeturner.com/organum-duplum/. have been faced with a difficult choice: either to sing from an unsatisfactory modern edition, or personally to conduct lengthy research and sing from the original notation. Needless to say, this has not encouraged the performance of this music.

How has this situation changed in the light of the recent completion of the L’Oiseau-Lyre edition? To what extent can — and should — the practising musician base his or her performance of organum duplum on the scholarship of the compilers of this edition? Is further reference, either to the original source notation or to other theoretical writings on this subject, now redundant?

During a presentation for the Orpheus Research Centre in Ghent, I argued that modern transcriptions were on their own inadequate when preparing and performing organum duplum and that it was imperative to work from original notation.2)Penelope Turner: ‘The Need for Artistic Experimentation in Preparing Organum Duplum for Performance — L’Ecole de Notre Dame, Léonin and Pérotin’. Presentation for the Orpheus Research Centre in Music (ORCiM), April 2011. I suggested that our modern notation is inherently too rhythmically restrictive, and that the flexibility and improvised nature of this music can only be recaptured by referring to the original manuscripts. In this article I reconsider this assertion with reference to the most recently published modern edition of organum — the magnificent seven-volume Magnus Liber Organi3)Magnus Liber Organi, ed. by Edward H. Roesner and others, 7 vols (Editions de L’Oiseau-Lyre, 1993–2009). (henceforth MLO). This edition transcribes into modern notation the organum4)The conductus and motets, while also to be found in the same manuscripts, are not contained in this modern edition. from all three of the main extant manuscript sources of Notre Dame School polyphony. Each volume also contains a useful introduction by the relevant editor explaining his methods and often providing excellent background information about this musical genre. There is editorial comment on the history and liturgical setting of organum and, to some extent, on the music’s performance.

As a musician who is passionate about Notre Dame School polyphony and who desires to promote the performance of this uplifting and extravagant music, I am delighted that this edition has been published. It is clear that it is of huge practical benefit to performers of organum duplum. Firstly, it solves the immediate problem that the manuscripts contain only the organa dupla sections, and not the plainchant that completes each work. In this modern edition a well-researched version of the plainchant is inserted, making the structure of each piece immediately clear. Secondly, as concerns sections of organum duplum in the discantus style5)In discantus passages of organum duplum, both the upper voice and the tenor are rhythmically active. (where correct rhythmic interpretation is frequently agreed upon), this edition is extremely helpful to a performer.

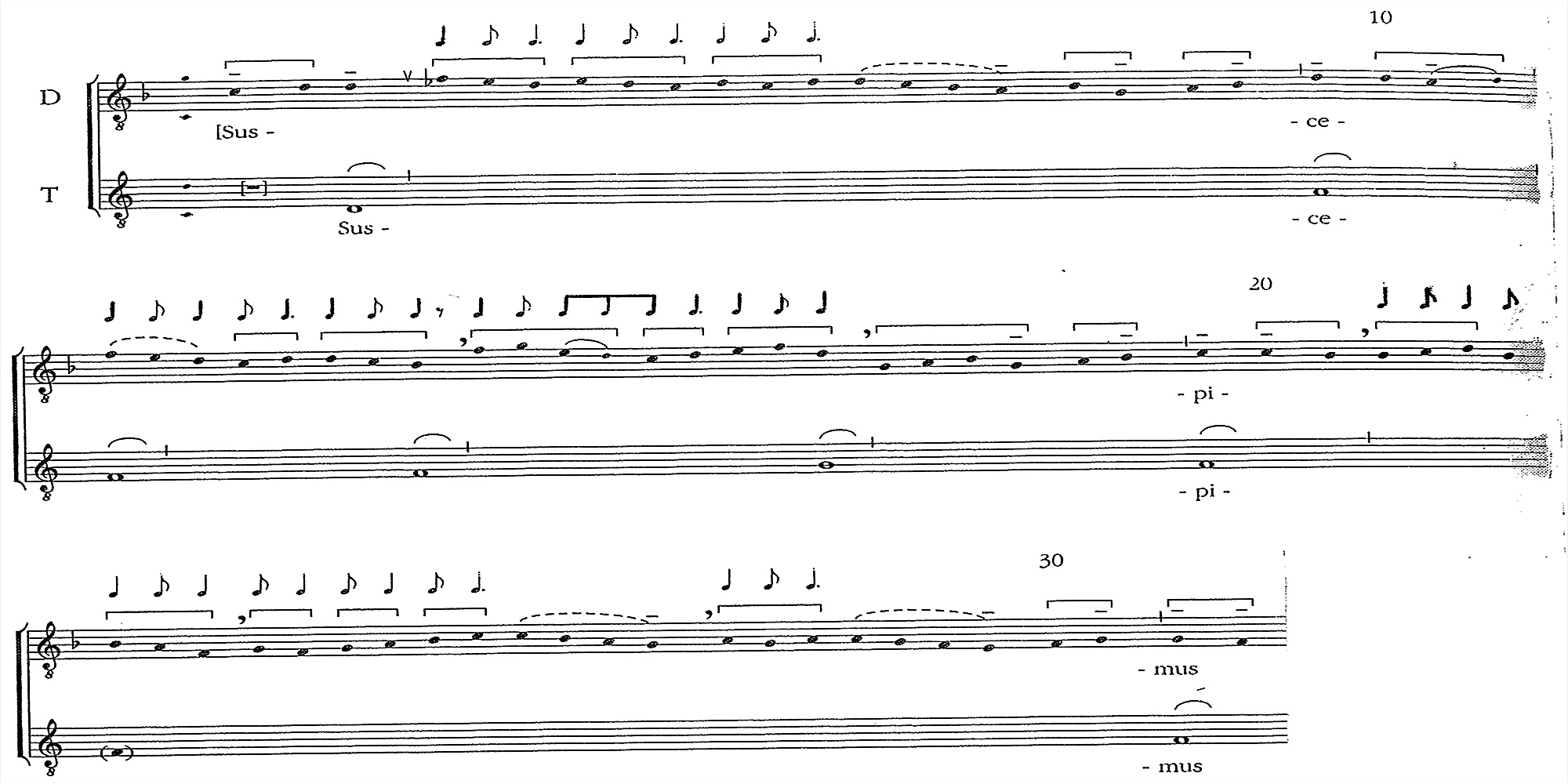

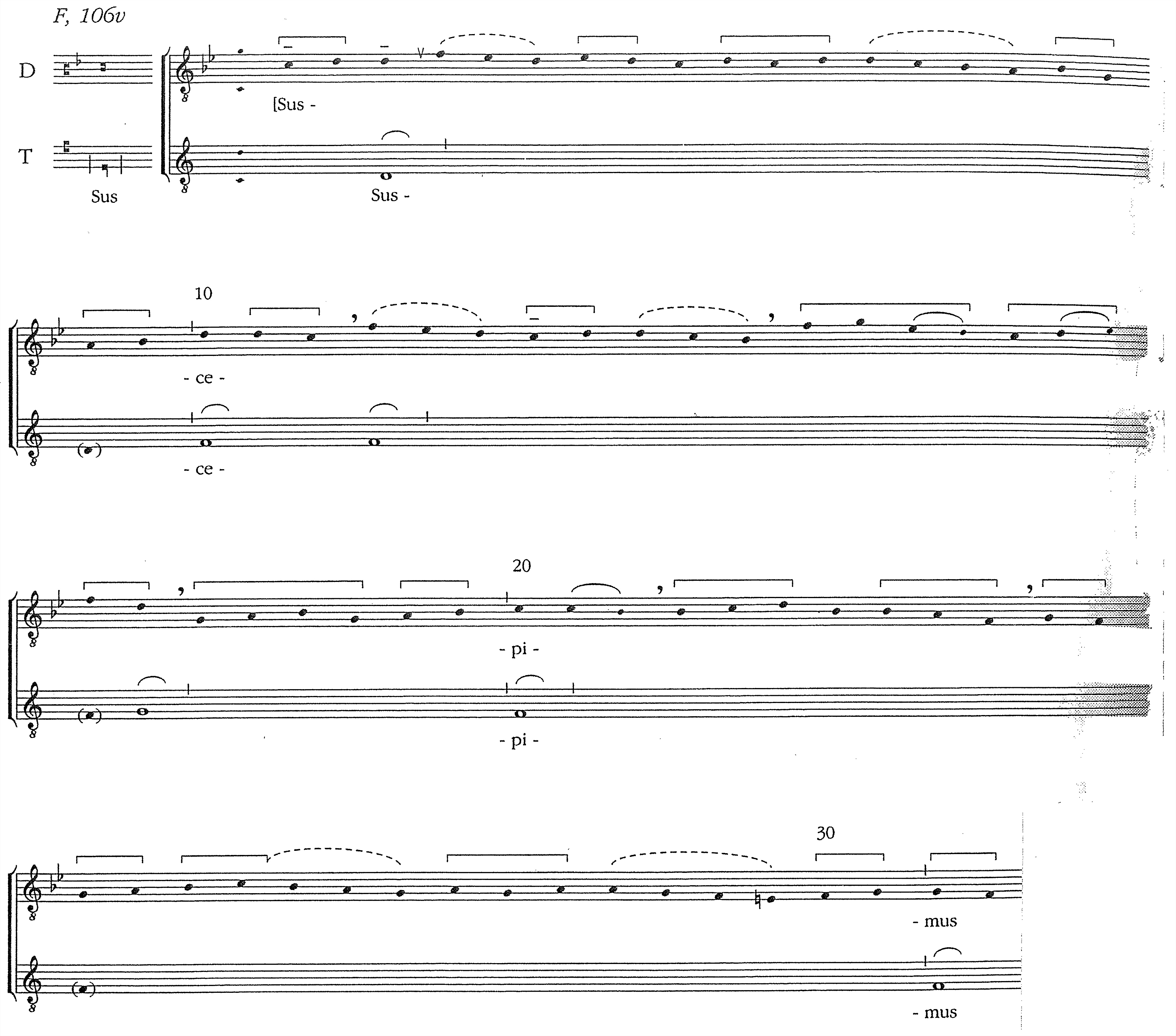

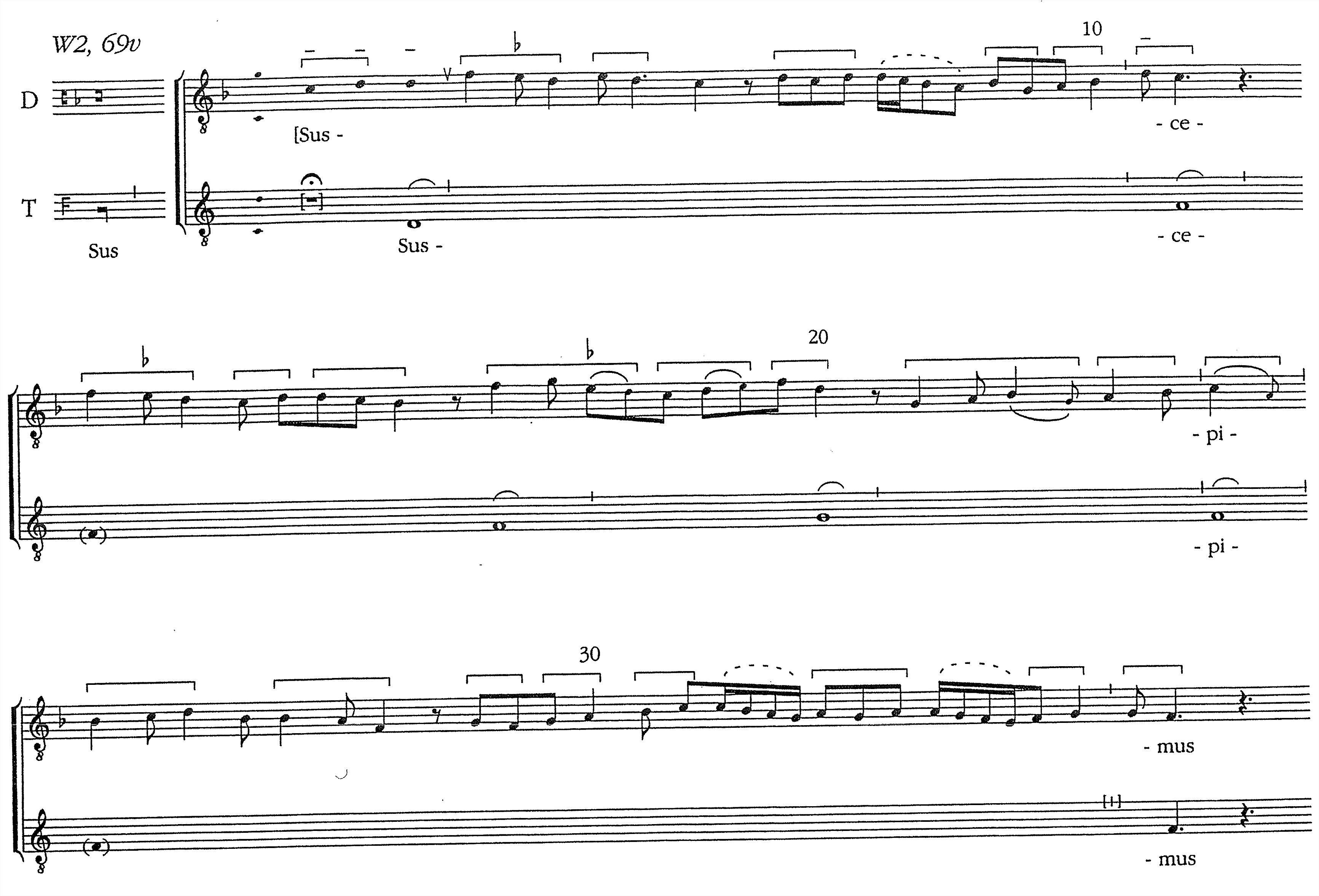

The main issues arise in connection to ‘sustained-tenor’ passages, where the correct rhythmic interpretation is debatable and the fitting together of the voices may also be open to interpretation. Is this modern edition helpful for these passages? Interestingly, the L’Oiseau-Lyre edition contains the work of three different editors, each of whom has transcribed the organa dupla from one of the three different major sources.6)Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibiothek, Helmstedt 628 (Heinemann catalogue 677; Figure 30) (‘W1’); Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Helmstedt 1099 (Heinemann catalogue 1206) (‘W2’); and Florence, Biblioteca Mediceo-Laurenziana, Plut. 29.1 (‘F’). Thomas Payne has transcribed manuscript W2; Mark Everist has tackled manuscript F (probably the best-known and most used of the three); and Edward Roesner has taken on manuscript W1. The editors vary in their approach, although they all abstain from using barlines, and all use stemless noteheads for ‘passages of unclear rhythm’.7)All three editors transcribe discantus passages into modern rhythmic notation. These differences in approach are well illustrated by a comparison of the Gradual ‘Suscepimus Deus’, a Gradual for Candlemas that appears in all three manuscripts.

‘Suscepimus Deus’, manuscript W1: Wolfenbüttel 628

Edward Roesner’s edition of W1, vol. VII (2009) is the most recent of the three editions. He uses stemless noteheads for all the sustained-tenor passages, but makes many rhythmic editorial suggestions where there is possible modal rhythmic content8)Six modal rhythms are described in the treaty ‘Mensurabili Musica’ (c. 1240) formerly attributed to Johannes de Garlandia. The English scholar Anonymous IV added reference to a further seven irregular rhythmic modes. The modal rhythms allowed rhythmic meaning to be conveyed by the number of notes in a ligature and the position of the ligature among other ligatures. for the upper voice within sustained-tenor passages (copula).9)The term ‘copula’ is difficult to define. Here it essentially describes short passages within sustained-tenor sections of organum duplum where the ligatures in the upper voice nonetheless suggest a rhythmic interpretation. He also gives suggestions concerning possible ficta additions.

‘Suscepimus Deus’, manuscript F: Pluteo 29.1

Mark Everist’s 2001 edition of F (vol. III) is the most rhythmically neutral of the three editions looked at here. He provides fewer editorial suggestions than Roesner for the copula sections. I found to my interest that Everist’s version of ‘Suscepimus Deus’ is compatible with a version I recorded with the vocal ensemble Trigon in 2000.10)Trigon: Music for Candlemas — Gregorian chant and early 13th century polyphony from the Ecole Notre-Dame. Passacaille label, 2000. Our two versions are not identical. For example, Trigon chose to insert a clausula in the verse. This suggests that for rhythmic passages of organum duplum there is a broad consensus as to how this music should be interpreted.

‘Suscepimus Deus’, manuscript W2: Wolfenbüttel 1099

Thomas Payne (vol. VI) takes a more rhythmically prescriptive approach in his transcription of W2. In ‘Suscepimus Deus’, for example, he uses the stemless noteheads only for the opening three notes of the upper voice (Figure 3), whereas for the rest of the sustained-tenor passages (‘organum purum’)11)Organum purum or organum per se refers to sustained-tenor passages of organum duplum where no particular modal rhythm is apparent (free rhythm). he has used modern rhythmic notation, though without staying rigidly in one particular modal rhythm.

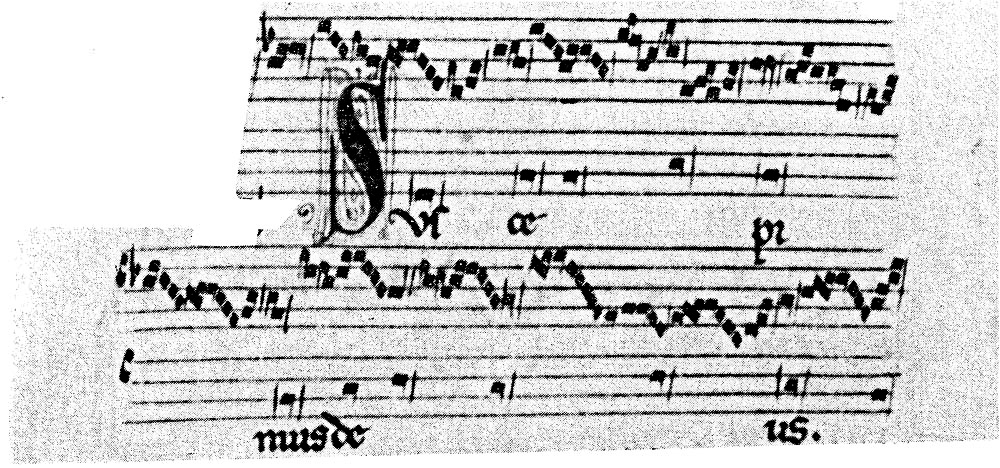

Payne admits in his introduction that his interpretation is in large part based on personal choice. He explains that he decided against a transcription of organum purum in neutral values because that approach ‘scrupulously avoids[, is] the semiotic force that the ligature groupings of each source exercise over a reader or editor.’ I agree with Payne that the manner in which the ligatures are grouped is all-important. How the ligatures look in the original notation has a direct impact on the performer. They guide the interpretation of the melodic line, even in passages of free rhythm. Thus the visual picture presented by the notation itself provides the performer with the beginnings of a rhythmic melodic structure; and this structure is not present when the ligatures are transcribed into neutral modern notation.12)Use of the original notation also encourages the recognition of recurrent melodic formulae. Compare the above modern transcriptions with the opening of the ‘Suscepimus Deus’ from manuscript F:

Figure 4 ‘Suscepimus Deus’, manuscript F: Pluteo 29.1. Facsimile reproduction of the manuscript ed. Luther Dittmer (2 vols), f. 106v (Publications of Mediaevel Musical Manuscripts, 1966–67: 10-11)

So, for those practising musicians looking for a modern edition of organum duplum from which to perform without having to refer to the original notation, it might seem to be Payne’s version that is of most use. Ironically, however, and despite the fact that I personally agree with many of Payne’s rhythmic editorial decisions,13)As regards the treatment of dissonance and consonance, my practical experience leads me closer to the solutions proposed by both Roesner and Everist. as a performer I find his approach too restrictive. I suspect that the organum purum sections in his edition would tend towards a fixed, lilting, ‘tum-tee-tum’ rhythm in performance, simply because of the way we are accustomed to read modern notation. The chances are that the flexibility of the upper voice’s originally improvised lines would be lost.

As for the freer approaches of Everist and Roesner, these cannot stand alone either, and are useful only if the original notation is used as the primary source. I agree with Payne, and suggest that the approaches of both Everist and Roesner give little help in shaping the melodic line. Indeed, I fear that reliance on their freer approach without reference to the original notation would encourage a note-by-note interpretation that is far from the ecstatic flow called for by this music.

My conclusion is two-fold. On the one hand, I find that this edition as a whole is an invaluable aid in the preparation of organum duplum for performance. It provides useful background information in the introductions, makes valuable editorial suggestions, and allows practising musicians to rely on the scholarship of knowledgeable academics. This edition makes organum duplum more accessible to those not yet familiar with it and significantly reduces the time and effort needed to prepare a piece for performance.

On the other hand, I remain convinced that this modern edition should only be used by performers as an aid to understanding the original notation. The rhythmic freedom of organum purum and the limitations of our modern rhythmic notation make the use of the original notation as the primary source the only satisfactory solution. Furthermore, reliance on the original notation obliges the performer to experiment — a process that necessarily plunges the performer more deeply into the music and allows him or her to make a personal interpretation (rather than relying solely on an editor). In this age of digitization, the best step forward would be to add to this modern edition a copy of each of the manuscripts in question. Were this to be done there would no longer be any reason why this unique musical genre could not be successfully performed more often.

The interface between theory and practice

The L’Oiseau-Lyre Edition provides a valuable link between the worlds of academia and performance and gives the editors a vehicle for putting their ideas into practice. This brings us to a more general question concerning the link between scholarly research and concert performance. There is a large and impressive body of research concerning organum duplum,14)In his introduction to vol. VII of the modern MLO Edward Roesner usefully lists all the original sources of organum and all the relevant theoretical treatises. See also the bundle of essays: Ars Antiqua: Organum, Conductus, Motet ed. by Edward H. Roesner (Ashgate, 2009); part of the series Music in Medieval Europe ed. by Thomas Forrest Kelly. the theorists of the time having left a complicated and sometimes contradictory picture behind them. How far do these academic essays help the performer, who is primarily concerned with bringing this music to life?

The answer is that many of the articles are helpful to the performer in providing background information, for example concerning historical context. Some have a direct relevance to performance. A good example is ‘The Performance of Parisian Organum’ by Edward Roesner.15)Edward H. Roesner: ‘The Performance of Parisian Organum’. Early Music, 1979. Here, Roesner discusses details of performance, which he backs up with reference to the theorists of the time. Many of the points he makes are reflected in his own transcription of the W1 organa dupla mentioned above — for example, his treatment of dissonance and consonance.

This article was brought to mind when I attended a concert by the Huelgas Ensemble in May 2011.16)Huelgas Ensemble/Paul Van Nevel in Eglise de Notre-Dame de la Chapelle/Kerk Van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Kapelle, Brussels, 31 May 2011. For my review of this concert, see www.penelopeturner.com/2011/06/01/the-magnificent-music-of-the-magnus-liber/ The programme comprised sacred music from c. 1000 to c. 1250, and included a piece of organum duplum. While the concert was in general well-done, and in part very beautiful, I was not convinced by the organum duplum interpretation. To give one example, the tenor, rather than the upper voice, was treated as the leading voice in the sustained-tenor passages. This resulted in what sounded like a drone with unrelated ornaments over the top of it, so much so that the two voices seemed virtually independent of each other and unaware of the intervallic play between them. In his article, Roesner argues that the tenor should not be a mere drone, and that it contributes subtly to the articulation of the musical fabric.17)See, in particular, pp. 175-76 of Roesner’s article referred to in endnote 15 above. He remarks on the consonant structure of the music and argues that the tenor must deliver his seemingly static line in a flexible and expressive manner, responding to what is happening in the other voices. This approach fits exactly with my own practical experience of singing this music.

My conclusion is that the academic research carried out in this field is ignored by performers at their peril. It provides vital background information and can underpin practical decisions (such as the number and type of performers; how to begin a piece; the way of approaching consonance and dissonance; and where ornamentation is appropriate). I am not necessarily advocating authenticity, here. Rather, I suggest that the more one understands about a particular style, the less likely one is to produce an unsatisfactory performance.

However, nothing can replace the benefits of preparing organum duplum through experimentation with the music itself. In fact, I believe that performance practice has much to offer the world of musicological research in return. Where there is a lack of clarity, or conflicting academic opinion (for example, concerning the use of dissonance or the manner in which one should ornament) practical experience and experimentation may well be able to inform the theoretical debate.

Footnotes

References

| ↑1 | Organum duplum is two-part polyphony that sets the solo sections of responsorial chants from the Offices and the Mass for performance on important feast days. For further explanation and definitions of related terms, seewww.penelopeturner.com/organum-duplum/. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Penelope Turner: ‘The Need for Artistic Experimentation in Preparing Organum Duplum for Performance — L’Ecole de Notre Dame, Léonin and Pérotin’. Presentation for the Orpheus Research Centre in Music (ORCiM), April 2011. |

| ↑3 | Magnus Liber Organi, ed. by Edward H. Roesner and others, 7 vols (Editions de L’Oiseau-Lyre, 1993–2009). |

| ↑4 | The conductus and motets, while also to be found in the same manuscripts, are not contained in this modern edition. |

| ↑5 | In discantus passages of organum duplum, both the upper voice and the tenor are rhythmically active. |

| ↑6 | Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibiothek, Helmstedt 628 (Heinemann catalogue 677; Figure 30) (‘W1’); Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Helmstedt 1099 (Heinemann catalogue 1206) (‘W2’); and Florence, Biblioteca Mediceo-Laurenziana, Plut. 29.1 (‘F’). |

| ↑7 | All three editors transcribe discantus passages into modern rhythmic notation. |

| ↑8 | Six modal rhythms are described in the treaty ‘Mensurabili Musica’ (c. 1240) formerly attributed to Johannes de Garlandia. The English scholar Anonymous IV added reference to a further seven irregular rhythmic modes. The modal rhythms allowed rhythmic meaning to be conveyed by the number of notes in a ligature and the position of the ligature among other ligatures. |

| ↑9 | The term ‘copula’ is difficult to define. Here it essentially describes short passages within sustained-tenor sections of organum duplum where the ligatures in the upper voice nonetheless suggest a rhythmic interpretation. |

| ↑10 | Trigon: Music for Candlemas — Gregorian chant and early 13th century polyphony from the Ecole Notre-Dame. Passacaille label, 2000. Our two versions are not identical. For example, Trigon chose to insert a clausula in the verse. |

| ↑11 | Organum purum or organum per se refers to sustained-tenor passages of organum duplum where no particular modal rhythm is apparent (free rhythm). |

| ↑12 | Use of the original notation also encourages the recognition of recurrent melodic formulae. |

| ↑13 | As regards the treatment of dissonance and consonance, my practical experience leads me closer to the solutions proposed by both Roesner and Everist. |

| ↑14 | In his introduction to vol. VII of the modern MLO Edward Roesner usefully lists all the original sources of organum and all the relevant theoretical treatises. See also the bundle of essays: Ars Antiqua: Organum, Conductus, Motet ed. by Edward H. Roesner (Ashgate, 2009); part of the series Music in Medieval Europe ed. by Thomas Forrest Kelly. |

| ↑15 | Edward H. Roesner: ‘The Performance of Parisian Organum’. Early Music, 1979. |

| ↑16 | Huelgas Ensemble/Paul Van Nevel in Eglise de Notre-Dame de la Chapelle/Kerk Van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Kapelle, Brussels, 31 May 2011. For my review of this concert, see www.penelopeturner.com/2011/06/01/the-magnificent-music-of-the-magnus-liber/ |

| ↑17 | See, in particular, pp. 175-76 of Roesner’s article referred to in endnote 15 above. |