Knowledge Production in Artistic Research

–Opportunities and Challenges

DOI: 10.32063/1009

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Situating Myself

- What Constitutes Artistic Research?

- Knowledge Modes

- ‘Worldmaking’ in Art and Artistic Research

- Interlude I – TransCoding and the Artwork Read me as an Example for Worldmaking

- The Fragility of Artistic Research – Opportunities and Challenges

- Interlude II: Embodying Expression, Gender, Charisma – Breaking Boundaries of Classical Instrumental Practices

- The Doctoral Programmes at Anton Bruckner Private University: An Example of Artistic Research in the Institution

- Postscript

Barbara Lüneburg

Barbara Lüneburg, professor for artistic research at Anton Bruckner Private University and director of the university’s doctoral programmes, is a performing artist and researcher of international reputation. Lüneburg’s arts-based research focuses on instrumental performance studies and the theory of artistic research. In 2022, the Austrian Science Fund awarded her the multi-year research project Embodying Expression, Gender, Charisma-Breaking Boundaries of Classical Instrumental Practices.

by Barbara Lüneburg

Music & Practice, Volume 10

Exploring artistic practices

Introduction

This article on knowledge production in artistic research and its opportunities and challenges has emerged from my practice as an artist and artistic researcher, from my position as director of the doctoral programmes at Anton Bruckner Private University, Austria, and from my work as a reviewer and consultant in artistic research. Knowledge production in artistic research is a political, regionally coloured and personal matter that also depends on the discipline in which one works. In my experience, it can easily be misunderstood, even misinterpreted, and bent in all kinds of directions for different purposes, not only by researchers but also by artists. I wish to address the diversity and plurality of approaches to knowledge production that I observe in artistic research, and to respond to some of the criticism that artistic research faces, by examining the peculiarities of gaining and disseminating knowledge through arts practice in music, and by taking a personal stand which, of course, is also regionally coloured and shaped by my cultural-political surroundings as well as by my personal profession, as artist, researcher, reviewer and teacher.

I will therefore include reflections on what constitutes artistic research – in my opinion – and how it differs from other academic disciplines or the process of artmaking itself. I am interested in what is necessary for the epistemological process and how, on the one hand, a multi-layered interpretation is fostered on research results expressed through art and artistic practice, but on the other hand, research results can also become ambiguous, making them vulnerable or sometimes questionable from the perspective of traditional academia or even within the discipline.

I address two modes of knowledge offered by artistic research: I investigate how philosopher Nelson Goodman’s notion of world-making can be critically applied in artistic research, touching on both opportunities and challenges in the research process, and I introduce the reader to a method I developed that uses artistic practice and first-person research to investigate embodiment in instrumental practices. Additionally, I will discuss the multi-layeredness and ambiguity of the representation of research findings when articulated through art. Examples from my own practice illuminate the theoretical foundations.

Situating Myself

I hold all knowing to be situated, indeed ‘shot through with our passions and interests,’ and, pace Foucault, part of the work to be done lies in the unpacking of discursive positions to reveal vested interests.[1]

My background is that of an internationally performing violinist in the field of contemporary music and multimedia art, an artistic researcher, and in this context also a composer. As an artistic researcher I focus on the epistemology and methods of artistic research; collaboration, and participatory art; charisma, concert aura and audience-performer relations; embodiment in instrumental practices; and performance studies in game-influenced artworks.

As an artist, I use the potential that a systematic research activity gives me to better understand and thereby further develop the process of my artistic practice, to let the findings flow back into my own art practice and that of others, and thereby to develop myself as an artist in the long term. The question that arises is: What are the conditions and challenges for gaining knowledge through artistic practice, and how will I articulate my research findings.

Serving as an editorial member the Journal for Artistic Research (JAR), the articulation of processes and outcomes is at the forefront of my interest. Every day, the multidisciplinary and multinational editorial team wrestles with how to understand artistic research, how broadly to define methodology in artistic research, what can be considered research at all, and how research findings are shared with or understood by audiences. We aim ‘to represent the diversity of positions and practices of artistic research regardless of whether or not they coincide with JAR’s approach’,[2] and we accept submissions in five languages (Spanish, Portuguese, French, German and English) to enlarge the spectrum of communities represented.

Institutionally, as the head of the doctoral programmes at the Bruckner University, I have yet another perspective on knowledge production in artistic research. As a teacher and programme manager, I need to introduce artists to an enquiring mindset that guides them reliably and transparently within the programme and on the way to their degree, and requires them to meet certain quality criteria in terms of academic rigour. At the same time, I also need to familiarise them with practices outside our doctoral programme that may have further or different criteria and requirements for artistic research. A sound toolkit, a comprehensive view of the discipline, and a transparent education are all important in addition to the professional perspectives for the doctoral students.

I will use my three professional vantage points to illuminate the scope, methods, potential and fragility of knowledge genesis of artistic research as I represent it in my practice. Thus, when I try to answer how knowledge can be acquired or produced through artistic practice, what constitutes the claim to knowledge in artistic research, how this knowledge can be articulated and shared in our discipline, I do so from my three professional positions, which are shaped by my performative and compositional practice in music and my interdisciplinary, often collaborative way of working.

What Constitutes Artistic Research?

And whether we call it artistic research, practice-based research, performance studies or practice studies, these fields of research are driven by the fact that we know and have experienced how conventional academic research ignores or disfigures important aspects of art and artistic practice.[3]

An important paradigm of artistic research is that researchers use their own artistic practice as an essential means for conducting research, i.e. research takes place through and in the act of making. ‘[R]esearch questions are embedded in and arise from practice’.[4] Methods emerge from the arts practice and lead back to it. We study our research questions by systematically exploring situations of production and through using the creative process as a way of thinking. Our practice becomes our research objective and at the same time a methodological tool. The researcher is deeply embedded in this process, which brings opportunities and challenges which I will address below.

Although artistic research finds its primary expression in art or artistic artefacts that can serve as testimony and evidence of the critical reflection of the research process and/or the research findings themselves, not every work of art is necessarily a representation of a researching process in the sense of artistic research. And while I am deeply convinced that the transmission of knowledge and knowledge gain through the arts defines the discipline of artistic research at its core, I also advocate the use of words, i.e. textual articulation of research to drive a further cognitive process which to me is intimately entangled with my reflexive practice in artistic research. As an additional aside, disseminating findings in text form, as is typical of the Western academic research tradition, helps to make research accessible to a wider academic audience, builds in-depth knowledge of artistic research in a broader research community, and establishes an easily accessible track record as an artistic researcher.

I am aware that this is a topic of controversy in the discourse on artistic research and that there are representatives who would rather stretch the limits of the scale towards the non-verbal artistic reflection. They might go as far as to propose the ‘idea of expanding [research] communication from verbal, linguistic, spoken or written languages to nonverbal modes of communication via image, sound and movement, and so on, which is somehow the normal way for artists to work’[5] as member of JAR’s editorial board Annette Arlander did beautifully in her ‘conversation with the pine tree’ in her video-taped contribution to the JAR session at the Society of Artistic Research Conference at Trondheim 2023.

Yet, working with artworks as a way of disseminating research findings can entail ambiguity. As works of art can open themselves up to a variety of readings academics may miss a ‘definite’ answer to a ‘clearly stated’ research question as they would expect to find in academic papers. And since the actual research investigation and process are integrated into the artwork and thus possibly obscured by the complex artistic embedding, the research results can be understood by the recipient in different ways, depending on the reader’s situatedness: their personal background, mood, experience and knowledge. Michael Schwab, chief editor of JAR, the Journal for Artistic Research responds to this:

However, here [in artistic research] knowledge is being enriched or increased in a way that we recognize while it may also be the other way around: that art works destabilize or suspend knowledge as we know it. In this case, a text may become deeper or denser, the simplicity of a historical argument more complex or an overall different ‘sense’ of what is at stake may emerge. Here, then, we have art radiating its own epistemicity into areas or modes usually kept distinct.[6]

I wonder whether the relative openness of art as evidence for research might even represent an opportunity for new and unexpected understandings to emerge much in the sense of what creativity researcher Sawyer calls ‘problem-finding creativity’[7] – ‘the posing of questions that may lead to new territories and innovation.’[8]

When Artistic Researchers use their own creative process and artistic practice as a source for their acquisition of knowledge, they operate from an insider’s perspective to investigate their research objective. Artistic researchers unearth ‘knowledge that’, as Erlend Hovland claims, ‘benefits from’ or, as I would argue, needs ‘a practitioner’s perspective, competence and “hands” in order to be developed.’[9] The researcher is deeply embedded in this process, which brings advantages and challenges that need to be consciously exploited (in the case of advantages) and addressed (in the case of challenges).

As I have said elsewhere, ‘[a]ccording to the demands and epistemic interests of their specific investigation, artistic researchers may take on different epistemological approaches. They embrace post-positivist, constructivist, transformative or pragmatic worldviews (to name but a few) and avail themselves of methods and tools not only from their immediate arts practice but also from disciplines of social science, philosophy and other humanities’.[10] We understand and develop our discipline by examining the relevant context in current research and art, bringing together theory and applied practice, body and mind. At its core – and I would like to emphasize this – artistic research is research for art, through art and with the means of art, which creates its own epistemological foundation. We act and think through our practice, that is, through our doing, which, as theatre practitioner and scholar Robin Nelson points out, is ‘anchored in the experience, the perception, the consciousness, the play, the tinkering’ of the artist. With Nelson, I understand the often-embodied nature of artistic research, artistic doing as an activity that is ‘not free of thought’. On the contrary, ‘attention to the body in practical enquiry does not exclude thought, but embraces it.’[11]

Finally, artistic research belongs to a domain ‘in which’ – as Foucault puts it – ‘the questions of the human being, consciousness, origin, and the subject emerge, intersect, mingle, and separate off’’.[12] In that sense, we use artistic research ‘to understand self and other’.[13]

Knowledge Modes

The specific nature of artistic research can be pinpointed in a way that it both cognitively and artistically articulates this revealment and constitution of the world, an articulation which is normative, affective, and expressive all at once – and which also, as it were, sets our moral, psychological, and social life into motion.[14]

What are the modes of knowledge that we deal with in artistic research? What kind of knowledge is acquired and why? Through artistic research we seek to gain knowledge for our discipline and our own personal artistic practice ‘to enhance understanding, reach multiple audiences and make findings accessible’ or to evoke a response and ‘make meaning through complicated and messy performances and products that have power and are evocative.’[15] We develop new approaches to our practice, advance theory, and make implicit knowledge explicit for others to observe and understand. Swedish choreographer and artistic researcher Efva Lilja puts it this way:

The object of artistic research is art. As artists we engage in research to become better at what we are doing, for the development of knowledge and methods. We introduce new ideas in order to rethink art, become leaders, increase audience engagement, investigate new presentation formats, tackle political and societal issues, or to develop sustainable practices.[16]

In most artistic research projects, methodological boundaries between disciplines are treated as permeable and the investigation is enriched by the inter- or transdisciplinary approach, however, the artistic creative process and the artwork itself are at the centre of the research practice. ‘[D]ata may be collected by doing art (such as performing, exhibiting, artistic software coding, sculpturing, etc., followed by critical reflection), by personal embodiment …, scientific experimentation, by connecting seemingly distant analogies or by exploring discontinuities to create new contexts within and through the artwork.’[17]

Artistic researchers may seek for different modes of knowledge, declarative and procedural, i.e. knowledge of what and knowledge of how, somatic and embodied knowledge, implicit tacit or aesthetic knowledge. Moreover, since artistic research is necessarily always concerned with human beings, if only because the researchers are at the same time the researching subject and their practice is the object of their enquiry, we can contribute to acquiring cultural and social knowledge and learning about aspects of being human in the world(s) we live in through a systematic creative and explorative artistic process. Art has epistemic potential in many ways. Knowledge resides in the arts and is brought to light through it.

In the following, I would like to introduce the reader to a critical view of a kind of knowledge-genesis that seems to lend itself in some ways to artistic research, namely ‘worldmaking’ as described by the symbol theorist and philosopher Nelson Goodman.

‘Worldmaking’ in Art and Artistic Research

What are worlds made of? How are they made? What role do symbols play in the making? And how is worldmaking related to knowing? These questions must be faced even if full and final answers are far off. [18]

In his book Ways of Worldmaking, Goodman claims that people make versions of the world using descriptions, symbols, metaphors and other representations in order to understand it. He states that in the process of worldmaking, intellectual understanding is accompanied by creative practice. Goodman emphasizes ‘the creative power of understanding, the variety and formative function of symbols’.[19] According to him a world cannot be found but is made. Goodman does not offer the reader a definition of what he means by ‘world’. Instead, according to philosopher Israel Scheffler, he meanders between two conflicting interpretations: an objectual interpretation, where a world is considered an object, ‘a realm of things (versions or non-versions) referred to or described by (119) a right [my emphasis] world-version.’[20]; and a ‘versional’ interpretation in which he suggests that ‘sometimes a cluster of versions rather than a single version may constitute a world’[21] and that ‘[m]ultiple actual worlds’[22] may pluralistically exist next to each other.

I am intrigued by the philosophical concept and what it could mean for art and artistic research. As artists, do we not use the creative power of understanding in our artistic work? Does that automatically make us (artistic) researchers? Some might argue that each artwork is a world in itself and that in creating these worlds, artists reflect and explore an external reality in the creative act and aesthetic product. We could argue that artists promote an understanding of a phenomenon, a context, a situation, an abstract notion or an aesthetic condition with their worldmaking when creating. Goodman claims that ‘[c]omprehension and creation go on together as perceiving motion … often consists in producing it. Discovering laws involves drafting them. Recognizing patterns is very much a matter of inventing and imposing them.’[23] Yet, does this process already qualify for it to be research?

I am convinced that world-making is a powerful tool that lends itself to artistic research, but at the same time I must urge caution when artists use Goodman’s idea of world-making too casually in the context of artistic research. Goodman describes worldmaking as a way of seeking knowledge (in German ‘Erkennntis’), not as an absolute search for truth. He points out that worldmaking in the phenomenological sense can be used to gather different insights about a thing, which can be equally valid even if they contradict each other. As philosopher Hilary Putman states ‘In [Goodman’s] view, this arises from two causes. First of all, perception is itself notoriously influenced by interpretations provided by habit, culture, and theory.’ [24] She continues ‘In the same way, there are different possible ways of reporting physical events and motions. And here too there is no sharp line to be drawn between the character of the object or motion and the description we give of it.’[25] For artistic research, Goodman’s emphasis on the symbolic, on metaphor and on the creative power of understanding is important when applied critically, for it is here that we can use our artistic and aesthetic tools and potentially unearth insights that would otherwise have remained hidden. So how can artists critically apply worldmaking such that it becomes a powerful tool for artistic research that goes beyond mere art production in its potential for insight? Theoretical philosophers Daniel Cohnitz and Marcus Rossberg explain ‘According to Goodman, the making of a world version is what has to be understood. … Making a world version is difficult. Acknowledging a great number of them does not make it easier. The hard work lies, for example, in creating a constructional system that overcomes the problems of its predecessors, is simple, uses well-entrenched predicates, or successfully replaces them with new ones (which is even harder), allows us to make useful predictions and so on.[26]

In this enumeration we find a fundamental difference between art or art practice for its own sake and art that serves artistic research. As artists, we work within a context, a tradition of skill and creation, which in turn is embedded in a cultural, social system. As much as we are part of this system, we are free to respond to it, to question it and to work with it randomly, if we wish so. The European Court of Human Rights has ‘underlined the importance of artistic expression in the context of the right to freedom of expression’.[27] Where does artistic research differ from pure arts practice? When artistic researchers use their art to make worlds, worlds that they study, and they use their practice to explore them, they are not supposed to invoke pure artistic freedom and do whatever comes to mind. Instead, while being highly creative and keep openness for serendipities, we at the same time strive for analytical rigorousness and explicitness.[28] In my opinion, worldmaking in artistic research should mean creating a symbol, a metaphor, a work of art that leads us to knowledge through a creative but controlled and systematic way of doing. As with any other research, we must first ask ourselves what we are trying to understand. Having chosen a topic to study, we systematically engage with it, collect data about it through our creative work, analyse and interpret it, draw conclusions, break down the original boundaries based on our findings, and thus make what Goodman calls a ‘world version’ that tries to replace some parts of the one we departed from with new findings.

Let us look at an example from practice: the research project TransCoding – From ‘Highbrow Art’ to Participatory Culture[29] and one of its main artworks the interactive audiovisual installation Read me in which the idea of worldmaking was used to investigate our research questions.

Interlude I – TransCoding and the Artwork Read me as an Example for Worldmaking

Through the artistic research project TransCoding – From ‘Highbrow Art’ to Participatory Culture (funded by the Austrian Science Fund, runtime 2014–2017, http://transcoding.info) we encouraged participation in the development of a multimedia show and an interactive audiovisual installation by offering participatory culture via the web 2.0. Our team built a network of social media channels around a main hub, the site what-ifblog.net. There we introduced our topics of multimedia art and contemporary (art) music, community participation, and the ongoing creation of our show under the categories ‘Art we love’, ‘You, us and the project’, and ‘Making of’, respectively. In a fourth category we chose ‘Identity’ as our main topic for the content of the show and the blog. The concept of identity offered a framework that is universally relevant and united our otherwise diverse international community.

The blog was our main contact point with our community, and it afforded them the opportunity to participate in our project. Via calls for entries, we encouraged visitors to contribute images, sounds and texts that we incorporated in our artwork. Through our social media channels we invited our followers to speak out, share discourse and influence the creation of our artwork, thus empowering them to express their own identities and participate in the creative process. We afforded our community members authority in shaping our work and offered them a platform for making their interest clear. As we invited contributors to exercise influence in the joint artwork, we looked at change as viewed through the power relationship between artist and community. We asked how granting creative influence to our community altered traditional (power) models of the artist–audience relationship, and strove to change the (commonly) hierarchic relationship between the artist and audience/followers into one of permeability and mutual influence.

Our main research objective was to involve an audience previously not available for the new arts in our project via social media, thereby creating a link between the world of young people coming from popular culture and that of multimedia artists, and thus making ‘highbrow’ art more accessible while asking: How can we further crossover between high art and popular art by offering creative and intellectual incentives, while listening back to and channelling the community’s own creative voices? Will this lead to a fruitful interactive exchange between the digital producers, followers and contributors and the researchers/artists while adding meaning to both groups? How does this challenge traditional power relations between creating artists and their audience?

On our social media channels, we created calls for entries, inviting our social media members to participate in the making of the emerging artworks via contributions in the form of texts, images, or music. Whenever I incorporated sounds, music, images, videos or texts from our community members into the artworks of TransCoding, I obtained consent of the authors, before releasing it. I only published or performed the artworks by mentioning the names of the contributors and the nature of their input alongside my own.

The creative work – and by this I include not only the emerging artworks, but also the work we put into our social media channels, such as communicating with and responding artistically to our online community – represents our worldmaking, which we used to capture the diversity of the topics we explored around our main theme ‘identity’ as well as to investigate the research questions around crossover art and interactive exchange, and power-sharing between community members/contributors and researcher/professional artists.

One of the central artworks of TransCoding, the interactive audiovisual installation series Read me,[30] may serve as an example for the worlds that were made within this framework. The installation was conceived by me, and I provided the original conceptual idea which consisted of the ‘technological setting and a conceptual frame that could be filled with the personalized artistic content of individual community members.’[31] Read me was part of our participative approach to art and conveyed an opportunity to investigate the kind of strategies we needed to apply to further and unlock the creativity of the community and test whether this led to a fruitful and meaningful interactive exchange between the community members and researchers/artists. With the installation, I intentionally shared authority over the artistic content with the people who approached me for their personalized version of it. Whereas the conceptual idea was provided by me, the first input for the artistic content was always provided by the person it was personalized for. The artistic content could be authored in parts or – if wished for– entirely by a single community member. In direct and active exchange with me the people who wanted to ‘own’ their version of the installation chose a portrait photo of themselves and provided me with their choice of a favourite text. They let me in in their favourite sounds, instruments, and music, told me childhood memories and present-day experiences, and guided me in the choice of instruments or sound elements they thought I should include for the soundtrack of the installation. Thus, they could shape and personalize the entire visual, textual and musical content of the installation to their taste and one person even decided to produce all the artistic material themselves.

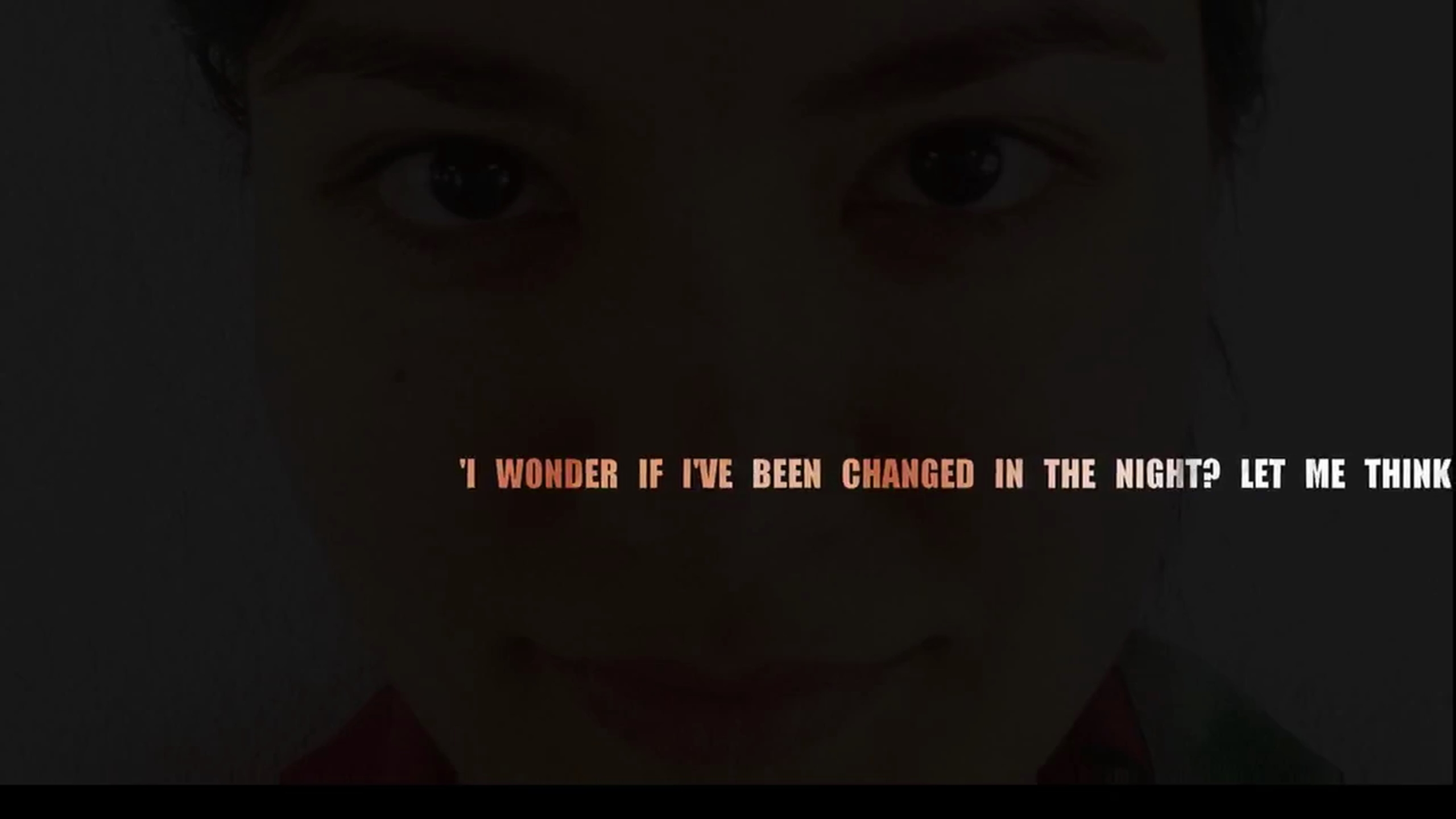

The basic artistic concept of the installation is as follows: Often our first impression of a person leads us to believe that we can grasp who that person is. It seems clear and obvious. But the closer we get to them, the more and more complex aspects of this person come to light. The idea was to mirror this experience in the installation. The proximity or distance of a viewer to the installation represents the closeness of the relationship one has with a person. It is measured via an ultrasonic sensor and translated into audio and text projection via an Open Frameworks-software patch and an Arduino. The further away a viewer is, the more unambiguous the material becomes (at the furthest limit, only one part of the soundtrack can be heard, one sentence can be seen on the projection, and the underlying image of the person shimmers through). It corresponds to our first impression when we get to know someone, that we think we understand that person immediately, even if we do not yet see them clearly.

Figure 1 Still of Read me (2015) in the version for Alina Murzakhanova. The onlooker is far away. Image © TransCoding.

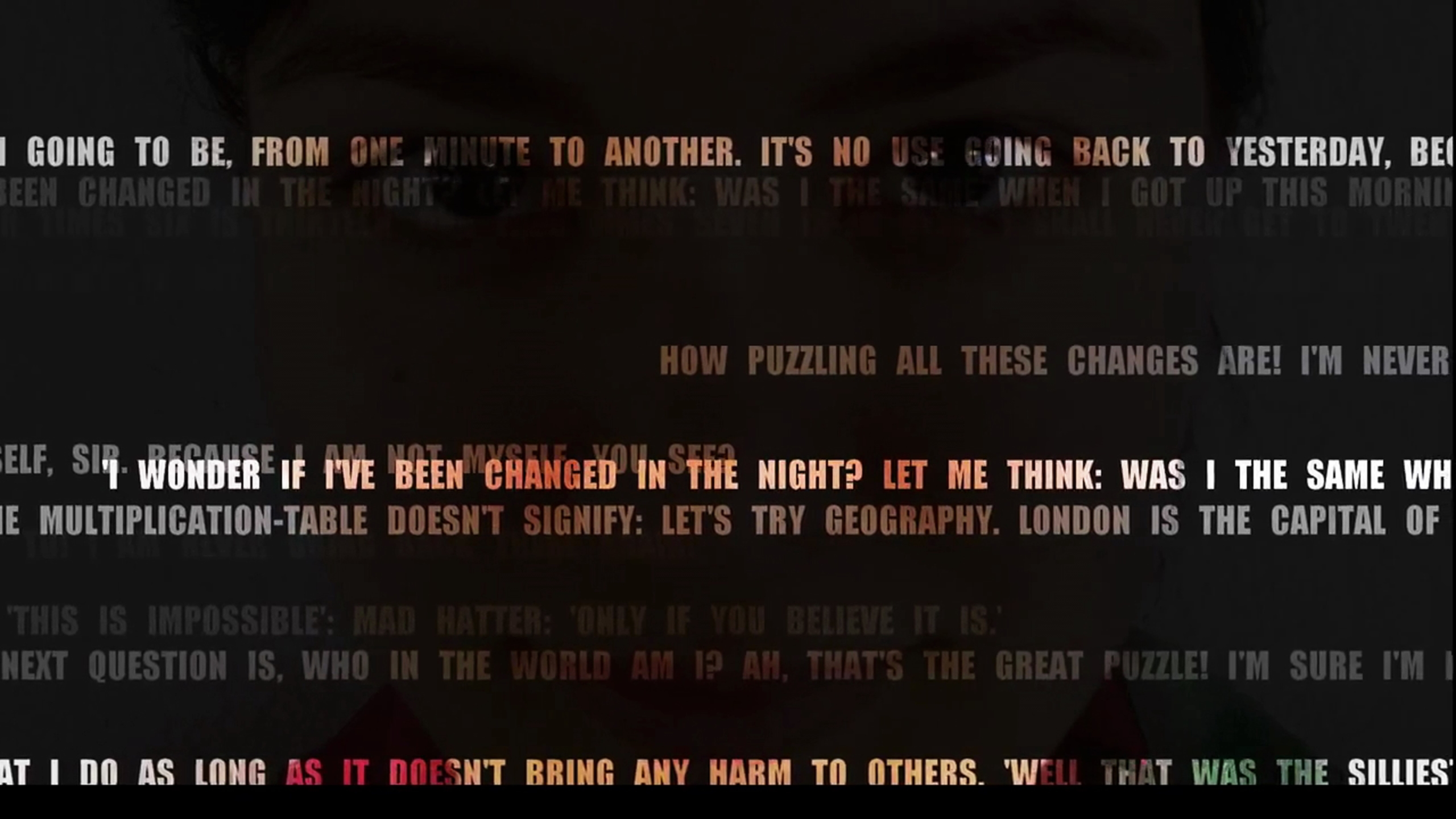

The closer the viewer gets, however, the more detailed and multi-layered the material becomes. More text fragments float across the screen, the music becomes more complex, and the underlying image of the person becomes clearer.

Figure 2 Still of Read me (2015) in the version for Alina Murzakhanova. The onlooker comes closer, more layers of text, music and image appear. Image © TransCoding.

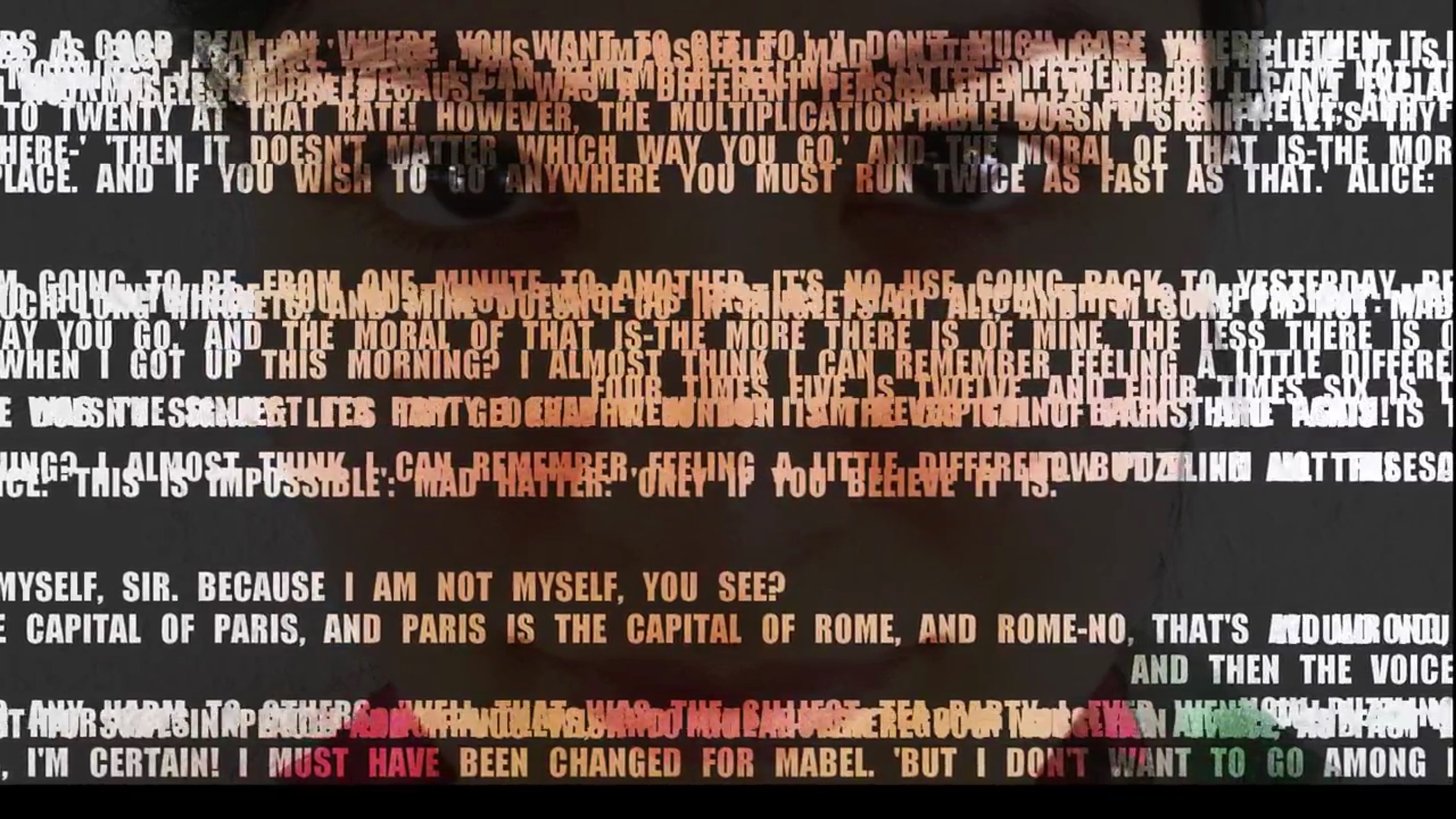

As soon as the viewer is very close to the sensors of the installation, all the layers of music and text appear. The text fragments cover almost the entire screen and thus open up the image behind them. Now we can see the person in the picture much more clearly, but the text fragments –partly overlaying each other– are not necessarily more readable, the content is more veiled. The sound, on the other hand, reveals more features of the person depicted. The viewer sees more, learns more about the person, but has the feeling that he or she may not know him or her as well as initially thought. Thus, the acoustic and visual content of Read me reflects the complexity of our impressions of a person.

Figure 3 Still of Read me (2015) in the version for Alina Murzakhanova. The onlooker is very close, all layers of music, image and text are perceived. Image © TransCoding.

Figure 4 Read me exhibited during the Austrian Long Night of Research 2016 at the University of Music and Performing Arts, Graz. The audience member is close to the sensors, many layers of image are revealed. Image © TransCoding.

As an example, I will present documentary videos of three different versions of Read me starting with the one personalized for Alina Murzakhanova: When I met Alina, she talked about art and life, and we exchanged experiences of what it is like to live in a foreign country. Living abroad sometimes reminded her of the world of the famous story of Alice in Wonderland: the grotesqueness of situations, the fractures in everyday life that come from being a foreigner, the uncertainty of right or wrong, those are questions she felt she was confronted with while living among people of another country. For her the text by Lewis Carroll encapsulated all this, and she chose it as the basis for her personalized version of the audiovisual installation Read me.[32]

Video 1: Documentation of the interactive audiovisual installation Read me (2015) personalized for Alina Murzakhanova; concept – Barbara Lüneburg; software programming and visual advice – Lia, Damian Stewart and Marko Ciciliani; composition – Barbara Lüneburg developed in exchange with Alina Murzakhanova (photo: Barbara Lüneburg); text fragments by Lewis Caroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland selected by Alina to represent her current life situation; sound material selected from the SoundCloud of the participatory what-ifblog.net project in consultation with Alina.

For her version of Read me, Gloria Guns, a human rights lawyer of Korean parentage, chose subsection 15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom and the lyrics of a song that expressed ‘a certain sense of isolation and alienation, stemmed by a longing for more beautiful deeper meaning’.[33] The material I used for the composition derives from Gloria’s contribution Fan Death[34] to our call for drones on the SoundCloud channel of TransCoding. One can hear her own voice singing a Korean lullaby that she incorporated in her drone for us. To express the alienation and isolation she feels when thinking about the text of her chosen song I combined some of her material with isolated fragments of a baroque aria.

Video 2: Documentation of the interactive audiovisual installation Read me (2015) personalized for Gloria Guns (photo: Denise LeBleu). Read me: Concept and composition – Barbara Lüneburg; software programming and visual advice – Lia, Damian Stewart and Marko Ciciliani; choice of text: Gloria Guns. The musical material is mainly derived from Gloria’s remix contribution Fan Death which she composed on occasion of the ‘Call for Entries: Drone Remix Contest’ as part of the participatory artistic research project TransCoding.

The composer and musician Ricardo Tovar Mateus saw the prototype of Read me at the arts event ‘Schmiede Hallein’ in September 2015 in Austria. He was immediately intrigued by the concept and started to think of his own version, which was to include not only his choice of image and text material but also his own music. Ricardo was inspired by philosophical texts by Slavoj Žižek, Michael Hardt, Gabriel García Márquez which circle around civil disobedience, thoughts about the purpose of our existence, love, negligence, discipline and anger. His music contrasts the fractions in the meaning of the texts by adding a contemplative and trancelike layer.[35]

Video 3: Documentation of the interactive audiovisual installation Read me (2015) personalized for and by Ricardo Tovar Mateus in November 2015 (photo: Tamara Pichler); concept – Barbara Lüneburg; text fragments – Philosophical texts by Slavoj Žižek, Michael Hardt, Gabriel García Márquez; composition: Ricardo Tovar Mateus.

There are many traces of the research process in the different worlds of the installation. Firstly – to speak with Goodman – each world version explores the ‘identity’ of the person for whom it was developed in a different way, embedding their contributions in the form of selected texts, image, sounds or their own vocal recordings, and sometimes even their own compositions developed specifically for their version of the installation. These contributions were responses to the conceptual and technical framework I offered, and each of them represented a metaphorical and symbolic interpretation of the contributor’s understanding of their own ‘identity’. Together we used the creative power and formative function of these symbols to gain insights into and understanding of the ways in which their ‘identity’ was formed and understood by them.

Concurrently, Read me offers an artistic articulation of further research findings, research that was concerned with the interactive exchange through offering creative and intellectual incentives to contribute to emerging artworks; with the sharing of power while listening back to and channelling the community’s own creative voices and with the impact this has on artists and art. Each world version of Read me offered a different take on crossover between high art, popular art (for instance prominent with Ricardo Tovar Mateus’ musical world) and even ethnically influenced art (in Gloria Guns’ choice of lyrics and her self-sung and recorded Korean lullaby). The aesthetic outcome was original in the sense that it showed influence of popular culture and Western contemporary art music but did not belong to any side. Last but not least, these examples of worldmaking represent a new kind of power relation between creating artists and their audience that challenged the traditional power relations in high art between creator and audience. In Read me, contributors could choose by themselves how much power they would like to yield over the final artistic product Ricardo Tovar Mateus designed all the musical, textual and visual content, Gloria Guns and I shared the creativity in composition, with Gloria providing the bulk of the underlying sound material, and Alina Murzakhanova was involved in the selection of image and text, but otherwise only wanted to be consulted on the musical realization of her installation without composing herself.

To summarize, following Cohnitz and Rossberg, the creation of a world version in artistic research could look like this: We recognize that the tradition of our discipline has blind spots, e.g. it does not question traditions, certain themes are avoided or not reflected, it has gaps or gives unsatisfactory answers. In TransCoding, we paid attention to and challenged the imbalanced power relationship between creators and audiences.

Therefore, we create a new construct or model of an alternative world that is expressed in art practice and tests the problems of the previous world. In TransCoding, we built a group of social media channels where art practitioners and their audiences could meet in an interactive and shared creative space and worked on creating situations that brought both together. With the installation Read me, for instance, we allowed audience members to take artistic control, partly or completely, and make it their very own.

We draw on existing knowledge and practices in the professional field in which we are researching, but at the same time we question them and replace them with new ones when this seems necessary. We introduced our online audiences to Western contemporary art and our way of making art while interacting with them on TransCoding’s social media channels. We listened and responded to the voice of the community by changing habitual processes of art making and communication. I consulted the person for whom the installation was personalized at every artistic step. While they chose the image and text, I adapted my personal musical aesthetic to the world of the person for whom it was intended. Alternatively, I shared authorship by taking their music and/or voice (always in consultation with the original author) and adding parts of my own music to the soundtrack, as in the case of Gloria Guns’s Read me. In the most extreme case, I relinquished authorship of the composition altogether and left it to the recipient of the installation, as in the case of Ricardo Tovar Mateus.

Through the art we create, with the world we make, we articulate the knowledge that is present in it, or the knowledge that we have recreated through our exploratory action: In TransCoding we created two main artworks Slices of Life,[36] for violin, video, soundtrack and artistic contributions of audience members, and the audiovisual installation Read me. In both artworks the voice of community members was as important and present as my own voice, which, in the resulting aesthetics, led to a crossover between different genres of popular culture and Western contemporary art music. Content and aesthetics of the resulting artworks are imbued with the research process. In that I consider the artwork Read me as well as the second main artwork Slices of Life, and the entire artistic set-up of the research project on social media an example of worldmaking that reflects the worlds we investigated and their multiple perspectives and the artistic-investigative processes we went through.

As a last critical afterthought, I would like to draw attention to the discourse in the sociology of the visual. According to sociologist Regula Valérie Burri, the sociology of the visual raises questions about ‘the extent to which images represent objective structures of meaning, i.e. the extent to which they can be interpreted as expressions of cultural interpretations, evaluations and orders of knowledge’. It investigates ‘how and by whom images are perceived and interpreted and thereby shape structures of meaning for their part, in that they not only affect bodies of knowledge but also influence and transform conventions of perception, interpretation and evaluation’. Finally, it traces ‘in which way, by whom and in which contexts images are used and to what extent practices of action … are (re)structured through them’.[37] Thus, visual representations (or in the case of arts and artistic research any sensory representations) have a context-specific and cultural meaning and conditioning that implies certain actions or understandings. If we now return from these considerations to worldmaking in artistic research, what does it mean for us? Even while the creative function of symbols and the creative power of understanding is a legitimate and powerful epistemological tool for artistic research, we need to remain vigilant as researchers and constantly ask ourselves about the cultural and social frameworks and conditionings in which we operate and the epistemological horizons that are accessible to us in our cultural and social upbringing to reflect on our own researching, thinking, acting and expressing. We constantly need to challenge ourselves on the relevance of our worldmaking.

I turn now to the challenges and opportunities that arise from the fact that researchers in artistic research simultaneously create what they study.

The Fragility of Artistic Research – Opportunities and Challenges

The essential difference between artistic and scientific research is that in artistic research, the goals and methods for acquiring knowledge are infused with the posing of questions that stem from the structured and reflective direct involvement of the artist in the process of creating the work and the artwork itself [my emphasis].[38]

As an artistic researcher, I am constantly asked by colleagues in other disciplines, by students, and by ordinary people who approach me about my profession: ‘How can you as an artist do research at all? What does that have to do with “truth”? Isn’t this starting point highly problematic?’ My answer is ‘yes and no’. The fact that artistic researchers simultaneously create the works and situations they study and then use the emerging artworks as expressions of the results of their research process brings challenges, but also offers unique opportunities.

It all starts with the fact that we are not only researchers but also need to be experienced artists. Our research questions and methods emerge from our arts practice, and if our experience is too limited, we are likely to ask questions that might not reach far enough. Possible bias or blindness caused by the proximity of artistic researchers to their research subject must be considered. Professional dependencies need to be acknowledged and conflicts arising from independent research vis-à-vis an artist’s professional position in the field need to be addressed with open eyes. What happens for instance when I come into conflict with my own self-image or professional standing because the art product that emerges from the research process, while valuable for research, does not meet the expectations I or my peers have of me? Do I lose commissions? Performances? Concerts? Or vice versa, the art is good, but the research is not. For example, am I merely confirming my research hypotheses with my art by adapting my art production to my purposes? At the same time, am I possibly satisfying not only my own but also the pre-formed assumptions in my professional field, albeit it completely unintentionally? These are all valid questions.

Ethical issues need to be addressed: Works of art are often created through the interaction of several people. Questions arise about authorship. Who ‘owns’ the art, the knowledge; who has what share and is this visible to the outside world? How does this affect my research? In art we often work with people; what impact does our research have on them? How do we deal with them respectfully? For instance, when artists conduct comparative research, colleagues working in their own professional field may come into their (possibly critical) focus. How can we anonymize data? Is that even possible? What happens to us, to our colleagues, if we fail? As artists and artistic researchers, we need to respond to these and other challenges and establish critical self-reflection in this multi-entangled process. How can this be achieved?

We give ourselves a stable framework, much as in other academic disciplines: In artistic research the philosophical stance of the researcher, methodology, data collection, data analysis and evaluation must be individually adjusted for each research project. Commonly adopted paradigms include phenomenology, pragmatism, post-modernism, post-structuralism, social constructionism or constructivism. Awareness of the paradigm on which we base our research, of our own background and the goal we are pursuing, as well as the systematic and consistent application of our chosen methodological tools, help us to gain distance and shift our perspective from pure art-maker to artistic researcher.

Data generation and collection starts with the creative process itself that is imbued in the entire research process up to the resulting artwork. It is often framed and accompanied by typical procedures and methods from other disciplines as for instance participant observation, field notes, thick description, phenomenological reflections, interviews, or queries. Literature review, the systematic study of art works as much as written texts and theory, helps us set a context. For analysis, we may develop our own systematization methods grounded in our artistic practice, that allow us to analyse, compare and evaluate our data, or we may apply tools of established methodologies such as discourse analysis, case study research, grounded theory, (sensory) ethnography, etc.

Artistic research seems to thrive in inter- and transdisciplinary teams where inspiration and learning reach into all disciplines. Robin Nelson claims: ‘Practice Research involves a being–doing-thinking that can generate new knowing across a range of intra-disciplines’.[39] In collaborating with colleagues from other disciplines, the artist’s first-person perspective is mirrored and critically scrutinized, which helps to balance personal or subjective aspects of an artistic researcher’s analysis and narrative when he or she investigates from an insider’s perspective that relates not only to the professional field itself, but especially to the actual creative process.[40] The additional use of proven methods from other disciplines as a tool for systematic documentation and analysis, with careful consideration of the personal or subjective aspects of artistic research processes and experiences, could provide artistic research with additional means ‘to address “subjectivity” and prior knowledge as a complex mix of resource and blinder.’[41]

Having talked about the challenges of gaining knowledge in artistic research, I will now focus on the possibilities that research from within a practice offers. First, I would like to highlight the insider’s perspective: Through artistic research we gain a detailed insight into the processes involved in creative work, such as the intentions we pursue, the development of the concept or the steps from concept to finished work, the artistic and technical procedures we use, the communication and decision-making processes, and how this is reflected in the artwork. Researchers looking at such a process from the outside (as for instance through practicing participant observation) may have limited access to the above information and the inside perspective, and certainly only insofar as the artist is willing to share it with them. The hidden rest is what sociology calls ‘under closure’. While being so closely involved in the researching process used to be considered problematic in many academic discourses, in recent years the debate has moved to a position that this kind of research is not only possible but also fruitful as long as one is reflexive about what one is doing. Artistic research, at any rate, considers it an invaluable advantage to have the insider’s perspective of the researching artist, if there is a balance in terms of critical self-reflection.

Artistic researchers argue that their research leads to understandings and insights that are difficult or impossible to obtain through other methods. According to them, the artistic-aesthetic experience that is shared in artistic research, as part of the research process and its findings, holds knowledge that is conveyed through senses, imagination and intellect and evokes a response that goes beyond verbally conveyed knowledge which is traditionally used in academic research. Moreover, they claim that artistic research ‘democratizes research, in the sense that audiences – other than those found in academia – might gain access to research knowledge through the experience of those artworks.’[42]

At the same time, artistic researchers must deal with the ambiguity of the representation of research results when they are articulated through art. How much do we want our colleagues or the public to understand us without using a standardized format, language or set of concepts such as are used in traditional research disciplines? To what extent do we engage with uncertainty and novelty in the representation of artistic research? Do we understand ambiguity as an advantage of metaphorical or aesthetic knowledge, compared to propositional knowledge? And if so, why? These are question that the board of JAR deals with every day. JAR’s Editor-in-chief Michael Schwab remarks:

Here at JAR we are somewhat obsessed with the importance of articulation. Rather than asking what art is and what knowledge is, we are concerned with the processes through which ‘art’ and ‘knowledge’ become qualified. … ‘Research’ in this sense is the singular term for the many directed processes of human and non-human articulation by which knowledges and also practices change. When we talk about ‘artistic research’ we mean to suggest radical inclusivity of a kind that challenges the gate-keeping set up around definitions of research, that is, the presuppositions that regulate who is allowed to speak and how. As the term suggests, this includes first of all artistic practices, but beyond this it includes potentially any kind of practice – given how little we know of the art of the future. Provocatively put, the aim of artistic research is not to add artistic contribution to the field of research, but to liberate research through the symbolic power of art.[43]

In the following interlude I will discuss my research project Embodying Expression, Gender, Charisma – Breaking Boundaries of Classical Instrumental Practices (funded by the FWF as project AR-749, short EmEGC). I will outline how we address the challenges of first-person research in its basic research design, in turn exploit its advantages by explicitly using methods from art practice to investigate instrumental embodiment in classical music from an insider’s perspective for basic research on this topic and use the artworks as a main channel for disseminating the research findings.

Interlude II: Embodying Expression, Gender, Charisma – Breaking Boundaries of Classical Instrumental Practices

In Embodying Expression, Gender, Charisma – Breaking Boundaries of Classical Instrumental Practices, violinist, composer and researcher Barbara Lüneburg, sociologist Kai Ginkel and flutist Renata Kambarova investigate how the instrumentalist’s body is an essential factor for musical expression, gender perception and charisma.

In the project we start from the assumption that the body is the medium with and through which instrumentalists realize sound and musical ideas and concurrently is the carrier and holder of emotions. Performers use gestures and facial expressions – consciously or unconsciously – as well as the staging of the body as a means of expression, communication and interaction with the audience. Through their physicality, they give the audience an insight into their individual, but also staged and culturally shaped, personality; and they are perceived and interpreted by the audience through the body as much as through their musical language.

The team understands the physicality of performers not only through musical expression, but also as technique and habit inscribed in their bodies through training, years of practice, cultural associations, lived values and individual personality. Emotions and thought processes are generated and represented in gestures, and bodily and artistic expression are interwoven with social messages, meanings and values. Body language thus plays directly into the value system shared with the audience and constructs not only the musical experience but also charisma.

Figure 5 Barbara Lüneburg performing Louis Aguirre’s Toque a Eshu i Ochosi for singing violinist. Photo: Maximilian Pramatarov.

In our research we take Western classical instrumental practice as a starting point, incorporate performances from classical to contemporary music, and translate findings into new artworks for violin or flute and multimedia, installations, exhibitions and performance formats.

The team applies methods of artistic research in the project that use the artistic process to uncover implicit embodied knowledge in the work of instrumentalists and make it explicit. To explore the meaning of the body of classical instrumentalists as a determining factor in musical expression and to recognize how musical expression manifests in and through the body, I have therefore developed a series of methods that are centrally based on the artist’s own artistic practice and need the inner perspective and perception of the practicing artist to gain knowledge. Based on the core method that I developed, ‘Re-enacting Embodiment in Classical Instrumental Practice’,[44] a performer first interprets and documents a specific work from the classical repertoire and then re-enacts another performer’s physicality in the interpretation of the same piece.

It is important to distinguish that ‘Re-enacting Embodiment’ in this method does not mean to recreate historical situations as done in historical interpretation research,[45] nor is it an act of acting in which a performer would try to ‘become’ soloist XY. ‘Re-enacting Embodiment’ is about precisely recreating the musical and physical interpretation, i.e., the ‘embodied techniques’ of another person with a focus on the experience the re-enactment evokes in oneself, skills that can be learned, and insights that can be drawn from it. The concept of ‘embodied techniques’ ‘differs from related concepts like performativity and habitus in that it emphasizes the epistemic dimension of practice.’[46]

In six distinct, carefully documented steps the re-enacting performer systematically explores this experience artistically and phenomenologically through their own body, to afterwards analyse and interpret the collected data using the methods of grounded theory. The process of musically and physically re-enacting another person’s interpretation provides in-depth insights into the intertwining of musical interpretation and embodiment. The instrumentalist-researcher is in a position to assess from an inner perspective what other performers do with their bodies when they express themselves and how this relates to and creates gender and charisma. By systematically addressing issues of embodiment in comparison or possibly even confrontation with the physicality of other performers, instrumentalists simultaneously expand their personal repertoire of embodiment techniques, develop an awareness of value systems in their performance and critically question their long-standing individual routines and artistic practices.

This method is inconceivable without the first-person perspective. It addresses the challenges involved by gaining distance through analysis and evaluation based on grounded theory, where this is necessary and helpful, for example, to counterbalance subjectivity. At the same time, we use the different interdisciplinary perspectives of the team members to balance the personal or subjective aspects of each artistic researcher’s work and experience and to collectively enrich the analysis and evaluation of the collected data.

Based on the work with the re-enacting embodiment method, other methods of artistic investigation have emerged. They include a variety of approaches and media, such as a series of remixes of audio-visual documentations of classical performances by renowned soloists from different generations and countries, the mixed media installation The Body that Performs (2022), and the ‘air violin’-performance Exploring Gestures (2023) by Barbara Lüneburg for soundtrack and violinist without violin and soundtrack. With these artworks and the creative processes they entail, I illuminate modes of knowledge and the epistemic potential offered by methods of artistic research – methods that are based on the inner perspective of the art-maker and make use of the broader spectrum of knowledge to which artists have access, such as somatic, kinaesthetic or phenomenological and aesthetic knowledge. The remixes for instance feature ‘individual movement patterns that are central to the expressive language of an individual soloist. For that I examine YouTube recordings of a performer for the expressive potential of their body movements. What characterizes their body language? How is musical decision making and execution expressed in their posture, facial expression, head tilt, upper body mobility, footwork, etc.?’[47] Next, I subject the original music to a three-to-five-minute remix to break the familiarity of the work, creating distance from the audience’s normal listening and viewing habits. Then I overlay the remix with body movements of the soloists taken from the recording by zooming in twice: once literally on the video footage, and secondly by slowing down the movements, sometimes extremely, to bring the viewer closer to details of the video and to emphasize facial expressions or movement patterns. With this kind of treatment of the original material, I create a work of art, or if you will I make a world version in which body language of the soloist and music, although perceived as belonging together, are nevertheless seen independently of each other. The expressiveness of the body can thus be viewed almost as if under a microscope, but not only analytically as we would strive for in purely academic research, but in the context of musical expressivity and art. Thus, the artworks that are created within the framework of EmEGC serve as a media rich articulation of the research findings that speak to the senses as much as to the mind.

In the section on worldmaking I presented a method that uses the creative potential of understanding as well as the aesthetic-epistemic potential of art for gaining knowledge in artistic research; in this section I have been concerned mainly with a method of artistic research that is based on the actual exercise of art practice for investigation and that leads to findings that can only emerge from the inner perspective of the artistic researcher. In the following and final section, I take a last, brief look at artistic research from my perspective as head of doctoral studies at Anton Bruckner Private University, as I think that the training of doctoral students places special demands on researchers and teachers in artistic research.

The Doctoral Programmes at Anton Bruckner Private University: An Example of Artistic Research in the Institution

There is something uneasy about the relationship between ‘artistic research’ and the academic world. This has led some people largely to exclude artistic research from the realm of higher education and research and assign it, instead, to art institutions that serve art practice directly – such as funding bodies, postgraduate artists’ laboratories, or exhibition venues. … In [this] strategy, artistic research is in danger of becoming isolated from the settings in which society has institutionalised thinking, reflection, and research – particularly the universities. Under a guise of artistic nonconformity and sovereignty, some people put up resistance to the supposed disciplining frameworks of higher education and research.[48]

Taking artistic research into its third cycle means having to deal with time-honoured institutions on the one hand and training students for today’s world with its enormous challenges on the other. The university is accountable to its students, to politics, to society and to itself, and it must constantly question and renew itself to give its students an education that enables them to face the demands of today’s world and offer solutions. Nevertheless, there is a pull towards the ‘known’, the established, and resistance to the still young discipline can be felt in many places. The recognition of artistic research in academia is therefore very much a political question, not only a question of content, and a question of power. Resistance goes both ways from academic scholars towards artistic research and from artists towards scholarly imbued research in and through the arts. The question of where we place artistic research and how we practice it can lead to the inclusion or exclusion of artists from social structures and financial resources.

How do we react to that at the doctoral programmes of Anton Bruckner Private University? Here, we run a structured and transdisciplinary programme, training academics and artistic researchers together in the same basic skills of research design, methodology and research-based thinking and practice. Without neglecting the specific methods and approaches of the disciplines represented in the doctoral projects, we strive for a modern understanding of knowledge acquisition through transdisciplinarity, and the applications of methods across disciplinary boundaries in the structured doctoral programme. We find it important to offer our doctoral candidates orientation, reliability, and transparency in the form of quality criteria that are set up for any examination in the doctoral programme (academic and artistic alike) in joint consultation with the team of supervisors. Much like Nelson we work on ‘clarification and provisional working definitions because the notions that “PaR” [Practice as Research or in our case ‘artistic research’] remains a conspicuously elusive idea’ and that nobody understands it can be unhelpful to colleagues and students who are seeking acceptance for their projects in formal HE [Higher Education] contexts.’[49] A clear framework offers students (and supervisors) at the same time clarity, protection and security in their work and studies.

At Anton Bruckner Private University, we emphasize the close link between practice and theory, which manifests itself, among other things, in questions inspired by practice, diversity of methods that draw from arts practice as much as from various academic disciplines in the humanities or sciences. We strive for permeability between disciplines and approaches, a critical understanding of the theory of research and a multitude of forms of dissemination that include textual discourse as much as artworks and arts practice. We see art and science in a continuum of knowledge acquisition on which different modes of knowledge from ‘knowing what’ to ‘knowing how’ can be explored in an onto-epistemological application of what Nelson calls ‘being-doing-thinking’[50] and experienced as much in quantitative data such as numbers, graphs or formulae as in qualitative results such as discourses and artworks. Artistic research inspires the academic branches just as much as vice versa.

In our artistic doctoral programme, we explicitly pursue an artistic-scholarly approach. We draw our doctoral students’ attention to the differences between pure art practice and research-based art practice and provide them with a methodological set of tools and questions that draw equally on established academic as artistic methods with which they can work reliably. Academic and arts practice imbue in each other modes of knowledge gain which cannot be addressed, won or explored on each own. Thus, we do not exclude borrowing from other academic disciplines. Research-based thinking and doing in a systematic explorative way is strongly at the forefront of the training. More than reflecting on their artwork in a form of ‘complementary writing’,[51] we demand a thorough textual examination of their own practice for the doctoral project in the form of an extensive written thesis, next to their presenting findings through their art. We do not see this as a restriction of artistic research and individual doctoral students, but as support and enrichment of their doing.

It goes without saying that the teaching we offer to the doctoral students includes a discussion of the various forms and manifestations of artistic research, such as those shown by JAR or those brought to our institution by guest lecturers. And where our doctoral candidates set off to when they leave us after their doctorate, we are curious to learn.

Postscript

I have come to an end with a topic that divides colleagues and brings new allies, that leads to engaged and heated discussions, a topic that is met with scepticism, or fascinates and enriches and at the same time unsettles and shakes some to their foundations. The discourse on artistic research is engaged and lively, many areas are being discussed, different people, countries, art disciplines, related political and cultural contexts and knowledge cultures are exploring various solutions, questions are still waiting for answers and possibilities are in the air. As much as some parties sometimes wish for more certainty, the field of artistic research is far from exhausted; on the contrary, there is still much to be explored. In this sense, I would like to quote a historian friend, Nicolas Trépanier, with a perhaps somewhat unsettling but also beautiful thought from his book Foodways and Daily Life in Medieval Anatolia:

It is, after all, difficult to fully appreciate the value of a dimly lit zone of knowledge until we become aware of the expanse of darkness from which it was conquered.[52]

For me, artistic research, or practice as research, or whatever one wants to call it, has opened an experience of enormous growth and richness as an artist, as a researcher and as a human being. I am tremendously grateful for those who have opened this path for me. With this article, I contribute to the discourse and offer my approach to it from the perspectives that guide me in my professional work.

Endnotes

[1] Robin Nelson, Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond) Principles, Processes, Contexts, Achievements, 2nd ed. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), 12.

[2] Journal of Artistic Research, post on facebook, www.facebook.com/journalforartisticresearch (7 April 2023).

[3] Erlend Hovland, ‘Death in Bologna: An Essay on a Manifesto against Artistic Research.’ in MUSIC & PRACTICE 9 (2021) DOI: 10.32063/0908.

[4] John Freeman, Blood, Sweat & Theory: Research Through Practice in Performance (Faringdon: Libri, 2010), Kindle location 184.

[5] Annette Arlander, Quoted from her video-taped contribution to the JAR session at the Society of Artistic Research Conference at Trondheim 2023 (minute 2:00–2:20), accessible at Journal for Artistic Research – Urgencies, 14th SAR conference 2023, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, www.researchcatalogue.net/view/2079976/2079977.

[6] Michael Schwab, ‘Editorial’, JAR: Journal for Artistic Research 28, www.jar-online.net/en/issues/28.

[7] R. Keith Sawyer, Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 73.

[8] Barbara Lüneburg, A Holistic View of the Creative Potential of Performance Practice in Contemporary Music. (PhD diss., Brunel University, 2013),15.

[9] Erlend Hovland, ‘Artistic Research and the Need for a Paradigmatic Shift in Art Research’, JAR: Journal for Artistic Research, Reflection, 29 December 2022, www.jar-online.net/en/artistic-research-and-need-paradigmatic-shift-art-research.

[10] Barbara Lüneburg, ‘Worldmaking – Knowing through Performing’, in Knowing in Performing: Artistic Research in Music and the Performing Arts, ed. Annegret Huber et al. (Bielefeld: transcript, 2021), 188.

[11] Robin Nelson, Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond): Principles, Processes, Contexts, Achievements 2nd edn (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), 19.

[12] Michel Foucault, Archaeology of Knowledge. Translated from the French by A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972), 4.

[13] John Freeman, Blood, Sweat & Theory: Research Through Practice in Performance (Faringdon: Libri Publishing, 2010), Kindle location 181.

[14] Henk Borgdorff, The Conflict of The Faculties (Lieden: Leiden University Press, 2012), 24.

[15] Maggi Savin-Baden and Claire Howell Major, Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice. (Milton: Routledge, 2013), 299.

[16] Efva Lilja, ‘The Pot Calling the Kettle Black: An Essay on the State of Artistic Research’, in Knowing in Performing, 28.

[17] Barbara Lüneburg and Kai Ginkel, ‘III. Artistic Research – New Insights Through Arts Practice?’ in Barbara Lüneburg, TransCoding: From ‘Highbrow Art’ to Participatory Culture (Bielefeld: transcript, 2018), 159.

[18] Nelson Goodman, Ways of Worldmaking (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1978), 1.

[19] Goodman, Ways of Worldmaking, 1.

[20] Israel Scheffler, ‘The Wonderful Worlds of Goodman’, Synthese 45/2 (1980), 201.

[21] Scheffler, ‘The Wonderful Worlds of Goodman’, 201.

[22] Goodman, Ways of Worldmaking, 2.

[23] Goodman, Ways of Worldmaking, 22.

[24] Hilary Putnam, ‘Reflections on Goodman’s Ways of Worldmaking.’ The Journal of Philosophy 76/11 (1979), 603.

[25] Hilary Putnam, ‘Reflections on Goodman’s Ways of Worldmaking.’, 604.

[26] Daniel Cohnitz and Markus Rossberg, ‘Nelson Goodman’ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Fall 2022 Edition, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/goodman/.

[27] European Court of Human Rights (2011), Cultural Rights in the Case-Law of the European Court of Human Rights, 5, www.refworld.org/docid/4e3265de2.html.

[28] Robin Whittemore, Susan Chase and Carol Lynn Mandle. ‘Validity in Qualitative Research’, in Qualitative Health Research 11/4 (2001) 527.

[29]The artistic research project TransCoding – From ‘Highbrow Art’ to Participatory Culture was funded by the Austrian Science Fund as project number AR 259-G211

[30] Link to the playlist of all four versions of the audiovisual installation Read me on youTube: www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLIUd8_lHH5lnmQg8OTK_-t0wE_DWeH0ij.

[31] Lüneburg, TransCoding, 19.

[32] Lüneburg, TransCoding, 97.

[33] Gloria Guns in an email to the author on 13 September 2015.

[34] Gloria Guns’ composition Fan Death on the SoundCloud of the participatory artistic research project TransCoding, https://soundcloud.com/gloriaguns/fan-death?in=what-ifblog/sets/drones-remix-contest.

[35] Description of Ricardo Tovar’s installation Read me cited from www.youtube.com/watch?v=CZpm5rT5sVk.

[36] Documentation of the artwork Slices of Life for violin, soundtrack and video on youtube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=sOzfntqyq1w&list=PLEwDq_Xgx16jaenCVUy-XxFuONro4y0JS.

[37] All extracts in this paragraph are taken from Regula Valérie Burri, ‘Bilder als soziale Praxis: Grundlegungen einer Soziologie des Visuellen / Images as Social Practice: Outline of a Sociology of the Visual’, Zeitschrift für Soziologie 37/4 (2008), 342–58 (my translation from the original German).

[38] Lüneburg and Ginkel, ‘III. Artistic Research’, 131.

[39] Nelson, Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond), 19.

[40] Lüneburg and Ginkel. ‘III. Artistic Research’, 160.

[41] Mats Alvesson, ‘At-Home Ethnography: Struggling with Closeness and Closure’, in Organizational Ethnography: Studying the Complexity of Everyday Life, ed. Sierk Ybema, Dvora Yanow, Harry Wels and Frans Kamsteeg (London: SAGE, 2009), 160 and 166.

[42] Lüneburg and Ginkel. ‘III. Artistic Research’, 132.

[43] Michael Schwab, ‘Editorial’. JAR: Journal for Artistic Research 24. https://www.jar-online.net/en/issues/24

[44] http://embodying-expression.net/english/re-enacting_embodiment.html.

[45] See Kai Köpp, Johannes Gebauer and Sebastian Bausch, ‘Chasing Dr Joachim – Die Jagd nach Dr. Joachim: Joseph Joachim, Romanze in C-Dur. Reenactment der Aufnahme des Komponisten, 1903’, in Arts in Context Kunst, Forschung, Gesellschaft, ed. Thomas Gartmann and Christian Pauli (Bielefeld: transcript, 2020, 86–99.

[46] Ben Spatz, What a Body Can Do: Technique As Knowledge, Practice As Research (London: Routledge, 2015), 16.

[47] Barbara Lüneburg, ‘Embodying Expression in Classical Instrumental Performance Practice’, in Music in Motion, ed. Stephanie Schroedter (Vienna: mdw-press, in preparation).

[48] Henk Borgdorff, The Conflict of The Faculties (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2012), 59.

[49] Nelson, Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond), 11.

[50] Nelson, Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond), 19

[51] Nelson, Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond), 25

[52] Nicolas Trépanier, Foodways and Daily Life in Medieval Anatolia: A New Social History (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014), 122.