Dialogo fra Arte e Tecnica; or,

Physicality and Mechanical Efficiency as Seen in Keyboard Treatises and Methods up to 1800

DOI: 10.32063/0106

Stefania Neonato

Stefania Neonato was awarded a doctorate for her research in the Historical Performance Practice Department of Cornell University under Malcolm Bilson. She has published in Early Music, Harpsichord & Fortepiano and Keyboard Perspectives. In 2007 she won the International Fortepiano Competition in Bruges, and has since performed around Europe and North America.

by Stefania Neonato

Music + Practice, Volume 1

Explorative

Given the evolution of keyboard instruments from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, aesthetic shifts in keyboard writing should come as no surprise. A more pronounced shift arose between what had been considered ‘art’ until the end of the eighteenth century and the new category of ‘technique’, which started appearing at the turn of the nineteenth century.

This division has an important precedent in antiquity. The ancient Greek word ‘τέχνη’ (téchnē) expressed the ideas of ‘quality’ and ‘art’ in whatever field of human knowledge (Rocci 1987: 1826). Later, the Romans subdivided the term into two categories: Ars and techne, whereby the former term still means art, theory, and quality, while the latter concerns ‘specialization’ in an art. A common root is still detectable at this time, but during the period, which concerns me here techne eventually came to be understood as the training necessary to become an artist, and the initial stages of learning an art.

In the particular field of music, wherein practice (techne, ultimately) is the fundamental aspect of learning, this division generated a fertile change in perspective mirrored by the change of titles in the major keyboard tutors: the ‘art/Kunst’ of the eighteenth century treatises becomes more modern ‘instructions/method/course/Schule/Anweisung’ in the later methods (starting in the nineteenth century). There are two apparent exceptions to the rule: whilst Daniel Gottlob Türk’s Clavierschule (1789) has the words Anweisung zum Clavierspielen on its front page, aesthetics plays a fundamental role in the text; and despite the title of Johann Peter Milchmeyer’s Die wahre Art das Pianoforte zu spielen (1797), it is a ‘course of instructions’ in all but name.1)The dedicatees of the two tutors appear to be quite different. Türk addresses his work to ‘students, teachers, scholars who can give to music matters further reflection on different topics’ (Türk 1997: 2); Milchmeyer writes for ‘amateurs and beginners of pianoforte playing’ (1993: 3). Regarding the evolution of the categories of Dilettanten and amateurs, it should be said that, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and as long as the consumption of music was associated with the nobility or with the dawn of the bourgeoisie, the terms did not indicate level of skill or knowledge in music but the fact that it did not represent a profession.

My examination will stop at the end of the eighteenth century when the new fortepiano replaced the clavichord and harpsichord as preferred instruments. At this time there was also a dramatic change in social environments, and consequently in ways of perceiving and teaching music. On the one hand, teaching music was usually regarded as a theoretical subject, whilst on the other hand, the art of playing an instrument was considered to be a necessary but somehow more modest, ‘practical’ knowledge. Both these fields were given as assignments to individual teachers up to the mid-eighteenth century at least. In them teachers could transmit their knowledge to other young musicians or to the aristocracy. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the consumption of music moved out of the elite environments of court and church and into bourgeois homes, concert halls and opera houses. This created the need for more widespread artistic ‘production’ and a better organized training period for performers, which eventually led to the establishment of conservatories in many European major cities. The ‘art of playing’ an instrument, until then only an aspect of a more complete musicianship, was no longer something that one learned from a master or a composer, but became an independent discipline. The huge demand for instructions on ‘how to play’ pushed musicians to write and sell methods that would compete with the ‘official’ ones of the conservatories and ultimately with teachers. Some of the manuals still ask for a teacher as an intermediary between the text and the student, while others claim to be useful even without such guidance (Milchmeyer’s tutor being one of these). Some of them are very detailed and some are more synthetic, as with those by Jan Ladislav Dussek (1796) and Muzio Clementi (1801), who were both active in London where a larger market required concise and clear instructions.

A music-master in the last decades of the eighteenth century could have chosen to adopt the traditional way of teaching — knowledge of music first, and application of that knowledge on an instrument second, or to teach the ‘new way’ — instrumental teaching first, and knowledge of music extracted from practice second. Furthermore he also could choose between teaching professionals or amateurs.2)Not only keyboard methods followed this model. The violin tutor, Elementi teorico-pratici di musica, by Francesco Galeazzi, for instance, stresses the importance of theory first, followed by practice (1791: 52). In order to illustrate some of these changes, I will stage a fictitious dialogue between two characters: Art, represented by the Master, and Technique as the ‘modern’ Executor, former student of the Master and now on his way towards a musical career. This dialogue may also serve as an example of how we today can approach and make use of historical sources in an imaginary way, in this case concerning the evolution of keyboard treatises geared to ‘technical’ instruction. One of the first such systematic courses of music was Libro llamado o arte de tañer fantasia by Tomas de Santa Maria (1565), whilst Milchmeyer’s Die wahre Art das Pianoforte zu spielen, which was the first ‘method’ for the piano exclusively, marked a turning point in music teaching and the acquisition of technique.3)Since Plato, dialogues have been the favourite formats for delivering knowledge in a creative way. Through the dialogue between two or more contrasting personae, a higher synthesis is usually reached. During the Renaissance and after, scientists and theorists in general used the ‘dialogue’ to organize serious treatises and essays in a lighter and more agreeable way (Galileo was one of them as was Diruta in Il Transilvano). I recommend the charming multiple-voice dialogue by Elizabeth Le Guin, ‘A Visit to the Salon de Parnasse’ in Haydn and the Performance of Rhetoric (Beghin/Goldberg, eds). Although the idea of my dialogue came before reading Le Guin, I consider her essay a brilliant confirmation of my purpose.

The form of a dialogue allows me to express doubts and questions, together with some answers. The whole matter of physicality and mechanical instruction in early keyboard methods still presents some obscurities, especially because the keyboard literature up to about 1700 did not actually need a sophisticated system of instruction in how to play effectively. The music itself was the instruction, for it contained both obstacles and sometimes the way to solve them. One thing has to be noted though, and that is that more practical instruction in ‘how to play’ was very likely transmitted in an oral way through a system of apprenticeship, and never recorded. So the only way we can speculate on the tradition of keyboard teaching in this respect is to examine the repertoire, however paradoxical this may sound.

A certain ‘resistance’ to treating physical efficiency as a respectable part of music education has roots in the medieval supremacy of mind over body, which was only partially overcome by the French rationalists. Still today, there is some resistance in examining the ‘best way of playing’ in the sense of the most efficient posture. There are of course various ideas on the subject but a more scientific approach, which is detached from ‘schools’ of music performance, has still to be fully articulated.

Dialogo fra Arte e Tecnica

ART (Master): Approach music with much respect and commitment.

TECHNIQUE (Executor): For sure, but how can I become the best performer of my time?

A: Following the precepts of the greatest music theorists: Tomas De Santa Maria, Girolamo Diruta, Jean Denis; and in the eighteenth century, Michel de Saint-Lambert, Francois Couperin, Jean Baptiste Rameau, Carl Philip Emanuel Bach, Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg, and Daniel Gottlob Türk. All of them gave complete and precious rules about how to become a good musician through knowledge of counterpoint, thorough-bass, harmony, ecclesiastical modes, how to accompany a cantus firmus or figuratus, how to embellish a melody, how to make a tablature, and the rules of Affektenlehre. So is this what you’re asking for?

T: Well, to tell the truth, I’ve been reading all these theorists writing about organs, churches, chants, intervals, keys, and so on and so forth… I don’t know how to put it, with all due respect, I find them a bit ‘dusty’ and they don’t actually explain the secret of the instruments.

A: WHAT! Are you one of those virtuosi who want to go up and down a keyboard as fast as you can with your fingers, but without your mind?4)In his Essay, Carl Philip Emanuel Bach warned against mere virtuosi who were capable of only playing the correct notes: ‘They overwhelm our hearing without satisfying it, and stun the mind without moving it’ (see § 1 in Chapter III ‘On Performance’). On the other hand, the word ‘virtuoso’ had a positive definition in earlier times. See, for instance, Adriano Banchieri’s caste division of musicians and organists into Vittoriosi; angels, saints and the celestial court, Virtuosi; religious and lay people who play in churches in God’s praise, and Vitiosi; ambitious and seditious musicians who play for mundane praises and interests) (1609: 64). At the time of its appearance, virtuosodefined somebody who had exceptional talent in intellectual, artistic, scientific or ethical subjects. In the Italian environment, the term had a strong relation with music, composers and performers. At the beginning of the eighteenth century in Germany, a virtuoso was a musician who possessed exceptional theoretical knowledge, and who applied it to composition or practical matters. Since about 1740, the term evolved to mean ‘concertists’, which was probably the first time that the term took on both positive and negative significance, this latter having to do with showing technical abilities for the sake of exhibition and self-affirmation. For a comprehensive history of the term virtuoso, see the entry in Eggebrecht, vol. 6.

T: Oh no, Master. I didn’t mean that… But the new instrument, the fortepiano, can actually produce sounds with different dynamics! An Italian seems to have invented the first gravecembalo col piano e col forte.5)Gravecembalo col piano e col forte was the first name for an instrument that presented all the basic characteristics of a fortepiano: hammer-struck strings, an action with the so-called ‘escapement’ of the hammers, and more generally the possibility of modulating dynamics. The credited inventor of the first fortepiano was Bartolomeo Cristofori from Padua, later an employer at the Medici court in Florence. A catalogue entry lists one of these instruments that was built in 1700.

A: This is not new! You can play dynamics on the organ, the harpsichord and especially the clavichord!6)Couperin discusses two techniques to modify the effect of the tone by either shortening or delaying it. According to him, these techniques give the illusion of dynamic changes on the harpsichord (Couperin, in Letnanova 1991: 24).

T: Yes Sir, but with all due respect, only with stops and polyphonic stratification, and in the case of the clavichord, who wants to play dynamics that nobody can hear?7)Milchmeyer, who wrote the first German piano method expressly meant for the pianoforte, was the first theorist to remark on the fact that, because the clavichord was almost impossible to hear, nobody would have picked it as an instrument for a concert (Milchmeyer 1993: XII).

A: This sounds like blasphemy to my ears, because I know the clavichord to be the most delicate, sophisticated and true-to-one’s-soul instrument that has ever been invented! And I’m not the only one who thinks this. Open Carl Philip Emanuel Bach’s treatise for instance, in the foreword of which he says clearly that fortepianos may be good instruments if solidly built, but that the clavichord has the advantage of the Bebung, which is a sort of vocal vibrato,usually impossible on a keyboard. And he adds ‘a good clavichordist makes an accomplished harpsichordist, but not the reverse’ (Bach 1949: 37—38). How could such superiority be stated more clearly?

T: It is clear in its words but if you move from a clavichord on which you played for a whole day to a fortepiano, that’s not going to work.

A: And why so?

T: Because your hands, your fingers get flabby and you are not able to play an even scale anymore… Milchmeyer was aware of this.

A: Who cares about scales and moreover, who cares about Milchmeyer, that Hofmechanicus, half inventor, half musician!8)Milchmeyer was at service at court in Mainz as an inventor (acc. to Gerber; in Milchmeyer 1993: XIII). Every court had a Hofmechanicus, who could also be a musician, on their staff. Rhein points out (ibid. IX–X) that Milchmeyer was a minor figure on the music scene: ‘his compositions are negligible, his teaching produced no notable performers, and he appears not to have been personally acquainted with any of the major musical figures of his time’. Moreover, he did not have the same literary talent as Quantz or Emanuel Bach. It is clear therefore how far removed he was from the mainstream music scene. I am most grateful to my colleague Christina Kobb for having pointed out an article by Michael Latcham of 2002 (‘Swirling from one level of the affects to another: the expressive Clavier in Mozart’s time’ in Early Music, XXX/4), where he quotes Milchmeyer’s own description in an 1783 advertisement about a ‘mechanical Flügel which can change more than 250 times by mixing the stops’. (The advertisement is found in Cramer: Magazin der Musik für das Jahr 1783, p. 1027; its reference in Latcham, p. 505). This notice contradicts what was previously believed about Milchmeyer’s invention, namely the fact that his three manual harpsichord had 250 stops. Latcham remarks that ‘250 combinations need at least eight stops’ (footnote 18, p. 516). Scales are to be known as keys, not to be played one after another as mechanical parrots.9)Emanuel Bach writes that the art of ornaments ‘requires a freedom of performance that rules out everything slavish and mechanical’. He suggests that one should ‘play from the soul, not like a trained bird’ (Bach 1949: 150). And I would be surprised if he could even talk of performance in a learned way. Besides, Bach writes that the harpsichord is the instrument on which to ‘develop proper finger strength’ (Bach 1949: 38).

T: But Milchmeyer gives suggestions in his treatise concerning how to place your body at the keyboard and how to use your fingers.

A: Do you really need somebody who tells you how to use your fingers on a keyboard?

T: Well, kind of…

A: Look, Johann Sebastian Bach as a keyboard player, finely portrayed by Johann Nikolaus Forkel in his 1802 biography, seemed to know what to do and with no doubts or effort:

Bach placed his hand on the fingerboard so that his fingers were bent and their extremities poised perpendicularly over the keys in a plane parallel to them. Consequently none of his fingers was remote from the note it was intended to strike, and was ready instantly to execute every command.

And he shows you even the consequences of this technique:

First of all, the fingers cannot fall or be thrown upon the notes, but are placed upon them in full control of the force they may be called to exert. In the second place, since the force communicated to the note needs to be maintained with uniform pressure, the finger should not be released perpendicularly from the key, but can be withdrawn gently and gradually towards the palm of the hand. In the third place, when passing from one note to another, a sliding action instinctively instructs the next finger regarding the amount of force exerted by its predecessors, so that the tone is equally regulated and the notes are equally distinct. In other words, the touch is neither too long nor too short, as Carl Philipp Emanuel complains, but is just what it ought to be (Forkel 1920: 50—51).

T: Well, this is mere description. We know that Bach, as organist and harpsichordist, and according to the resistance of very heavy keyboards (especially when two or more manuals were connected), had to adopt an efficient hand shape and action whereby his fingers were bent and apparently relaxed, but indeed very strong in their joints.10) In his treatise on the harpsichord, Couperin dealt with the importance of not forcing a child to play a multiple-manual instrument, which, he wrote, ‘will unavoidably strain his small hands to produce sound from the strings; this will result in a bad hand position and harshness in execution’ (in Letnanova 1991: 12).

A: Forkel goes on:

If the fingers are bent, their movements are free. The notes are struck without effort and with less risk of missing or hitting too hard, a frequent fault with people who play with their fingers elongated or insufficiently bent.

T: It’s so true! But does he explain why? No, he doesn’t! I’ve been observing and trying this posture, which is indeed very modern, and have come to the conclusion that you gain the best possible lever system when ‘only the top joints move’ (Forkel 1920: 52). In fact, the least movement of your knuckles the greatest and most direct action in the tips of your fingers.

A: In the second place,

The sliding finger-tip, and the consequently rapid transmission of regulated force from one finger to another, tend to bring out each note clearly and to make every passage sound uniformly brilliant and distinct to the hearer without exertion (52).

T: This is very much what I’ve been thinking for weeks, the concept of ‘economy’ in playing! But did he apply this technique to instruments like the clavichord?

A: Of course; he was very appreciative of the clavichord and the ways in which it could be used to modulate dynamics and different affects in a subtle way.11)Despite Forkel’s forthright view of the subject, it is not clear whether J. S. Bach was so fond of the clavichord. There is no evidence regarding the instruments that he possessed or the pieces that he may have written especially for the clavichord. See Schweitzer, pp. 200ff. Letnanova (93) reports Forkel’s argument about the clavichord without questioning it. During Bach’s time, ‘Clavier’ or ‘Klavier’ referred to a general category of ‘keyboard instruments’ (Forkel still adopts it with this meaning), while in the second half of the eighteenth century it came to define the clavichord, at least in the Germanic states. For more details, see the Introduction to Türk’s Klavierschule, § I, wherein he lists ‘organ, harpsichord, and the pianoforte’ beside the ‘true Klavier’, or clavichord. Forkel writes that,

Stroking the note with uniform pressure permits the string to vibrate freely, improves and prolongs the tone, and though the Clavichord is poor in quality, allows the player to sustain long notes upon it (52).

T: Master, I’m concerned about what you mean by ‘uniform pressure’.

A: Well, it must have to do with the issue of different fingers. It’s known that Bach elaborated an ingenious system to avoid using only the strongest and longest fingers in the hand.

T: His exercises…

A: Yes, he employed every finger in ‘passages in every conceivable position. By this means, every finger on both hands became equally strong and serviceable, so that he could play a rapid succession of chords, single and double ‘shakes’, and running passages with the utmost finish and delicacy, and was equally fluent in passages where some fingers play a ‘shake’ while the others on the same hand continue the melody (Forkel 1920: 52—53).

T: That sounds like he mastered the almost complete dissociation between flexor and extensor tendons!

A: I don’t know what you are talking about…

T: Well, when you play a scale, if your fourth and fifth fingers are raised while you play with the first three fingers, that’s a sign of bad dissociation. It’s quite natural that, when there is flexion in one finger, all the others tend to extend.

A: Excellent executors don’t usually have this problem.

T: I’m sure that they, like Bach, have more ease, but nonetheless they must have observed this phenomenon and have created a way to solve it. Do we have Bach’s own exercises?

A: No, we don’t; but I still believe that a good musician doesn’t need this kind of advice. After all, you can play or you can’t. It’s a matter of talent.12) Not so much attention was paid to physical matters when playing an instrument at this time. J. S. Bach and Couperin were revolutionary pedagogues but generally music teaching involved more theoretical subjects. Eventually, during the course of the nineteenth century the distinction between correct and beautiful performance encouraged teaching to focus on expression and taste, both related to ‘beautiful performance’. Of course, what can be taught and what cannot is still debated in pedagogic circles.

T: This means that I should stop then.

A: No, you’re a very talented executor and a musician of secure taste.

T: But I’m having trouble with difficult pieces, and I can’t find instructions on how to play them nicely on a fortepiano.

A: Go back to Carl Philip Emanuel Bach’s Versuch! He would advise you wisely!

T: I could recite his treatise by heart if you asked me to! He has a huge section on embellishments which you taught me with good taste, a quite useful chapter on fingering, in which he develops further his father’s innovations about the use of the turning thumb, but he doesn’t go on to explore how you get a nice touch, varied according to what you need to express. Even Forkel wondered why he didn’t elucidate this fundamental issue.13)‘I have often wondered why C. P. E. Bach’s Essay on the Right Manner of playing the Clavier does not elucidate the qualities that constitute a good touch. For, he possessed in high degree the technique that made his father pre-eminent as a player. True, in his chapter on ‘Style in Performance’, he writes, “some persons play as if their fingers were glued together; their touch is so deliberate, and they keep the keys down too long; while others, attempting to avoid this defect, play too crisply, as if the keys burnt their fingers. The right method lies in between the two extremes”. But it would have been more useful had he told us how to reach this middle path’ (Forkel 1920: 50). And the most frustrating thing is that he admits that a mediocre musician who possesses a good technique, gains better results than more talented performers who make mistakes and generally have poorer mechanical efficiency (Bach 1949: 41).14)That is, § 4 ‘On Fingering’: ‘Correct employment of the fingers is inseparably related to the whole art of performance. More is lost through poor fingering than can be replaced by all conceivable artistry and good taste. Facility itself hinges on it, for experience will prove that an average performer with well-trained fingers will best [sic] the greatest musician who because of poor fingering is forced to play, against his better judgment’. But still, no advice follows this statement!

A: ‘Mechanical efficiency’, what frightening words! The passage you mention is about fingering if I remember well, and fingering is an art as well!

T: It is a technique to be taught.

A: Why didn’t you mention the most interesting chapter of the Essay, the one on performance? There you find the most striking inspiration for a musician to follow: ‘A musician cannot move others unless he too is moved’ (152).

T: I love this… I do! But can you explain to me how I can be moved if my mind is busy trying to make my body work? What if my fingers refuse to work properly, what if my shoulders are stuck and my wrists are stiff? The more musical intention I want to put in a piece of music, the more I get tensed up, and consequently the less effective I am. Is there anybody who can instruct me to get that notorious ‘ease’ that everybody seems to regard as the most basic quality for making music?

A: The word is ‘taste’. All the greatest music theorists talk about taste and style.15)The keywords in the treatises from this time are Geschmack (taste) and Art. In the introduction to his book, Quantz lists these qualities as the ones that every musician should have (1966: 11); and in the chapter on ‘Good Performance’, Emanuel Bach admits the importance of equally developing the capabilities of both hands and that ‘good taste should be cultivated in the student right from the very beginning’ (in Letnanova 1991: 40).

T: What is style?

A: Francesco Galeazzi, in his 1791 treatise on violin playing, wrote that style is ‘a certain general way to perform, not easy to define, but to which only nature and a natural talent can contribute; not even a master can teach it’ (60).

T: I agree with this. If the soul of a musician does not ‘feel’ either excitement or peace, neither longing nor fulfilment, neither joy nor melancholy, you can’t teach anything to him. But usually such insensitive persons don’t approach music.

A: Alas, they do! And the poor master has to bear the faults of an unsuccessful training.

T: I see…

A: Especially nowadays, when everybody is very fond of ‘mechanical virtuoso skills and louder tone due to mechanical improvements in instruments, all resulting in a growing taste for sheer sound effects, and a broader sweep of melodic line’, it’s difficult to keep ears sensitive to the fine art of speaking and declaiming with such instruments.16)According to Ratner (1980: 422), these are new trends in music after 1800. The art of rhetoric is lost.17)It was commonly thought that a musician was an orator, ‘who with sonorous and gentle voice delights and moves’ (Banchieri 1975: 58). Emanuel Bach wrote that ‘the keyboardist more than any other executant can practice the declamatory style, and move audaciously from one affect to another’ (1949: 153). For an extended discussion of the declamatory style and music in the eighteenth century, see Barth, 1992. And taste is gone. This new fashion holds appeal for you as well, I see…18)‘On the whole, the English public, anticipating its Continental counterparts by more than a generation, favored a domesticated type of musical art catering to short-range emotional effects, often at the expense of structural solidity and logic’. Ringer (1970: 744) calls this an ‘escapist mentality’.

T: Well, only as far as efficiency is concerned. With the invention of the fortepiano and a broader range of dynamics and effects, keyboard writing has become quite challenging for the performer, and there’s no tutor that can instruct on this matter effectively. The only one who has tried to summarize the basic instrumental knowledge required from a piano player today is Johann Peter Milchmeyer. He gives very practical advice on the correct posture at the piano, with drawings about poor and good positions of the fingers, the importance of preparation in all passages, the way to play with different types of touch, and how to practice complicated figures. For instance, he writes:

If one wants to play the pianoforte with taste, then also all rests and the end of each melody must be observed, and at each rest, as well as the conclusion of each melody, whether short or long, the hands are to be taken off the keyboard. This must occur, however, with a certain calmness, and as it were unnoticeably, and not degenerate into a leaping motion. I call this a musical breath. The hands and fingers so removed can then prepare for the coming notes and passages; in this way one acquires an assurance in playing, will never be surprised by hard-to-find passages, chords, and notes, and avoids the mechanical movement of the arms (Milchmeyer 1993: 11).

A: A true musician knows how to practice every passage he encounters…

T: Some of them are really challenging. Composers now write scales in thirds and sixths, double grace notes in one hand, octave-runs, and fast tremolos at every corner.

A: And your ears are not offended by all these mechanical, meaningless figurations?

T (mumbling): Well, no or… yes! But it’s the new fashion and it’s in great demand among pianists.

A: And, from what I see you would like to be one of those pianists…

T: Yes!

A: Those whom Carl Philip would have called virtuosos and warned against! For he thought that: ‘Music must, first and foremost, stir the heart. This cannot be achieved through mere rattling, drumming, or arpeggiation’.19)Bach, Autobiography quoted in the Introduction to his Essay (1949: 16). Bach associated the style of Brechen or Arpeggiare — namely playing a chord by separating it into the individual notes, one after the other — with Italy. From harp playing, this style invaded keyboard practices and in particular harpsichord-playing. Bach blamed Italians for their tendency to roll chords, evidently a negative trait for him as ‘mere’ effect. He writes: ‘They can scarcely play a chord without breaking it’ (316, see also Burdette 1989: 4–6). These broken chords were common also in France. Couperin gives many examples of what he calls ‘batteries’ (Letnanova 1991: 15).

T: Those effects are great! They do stir the heart, they express storm, anxiety, power, supernatural effects, and with the stops you can even drive your listeners crazy!

A: Then Milchmeyer is capable of convincing the most experienced performer.

T: He knows what he’s talking about! He explains how to play octaves, thirds, tremolos effects, how to use stops and the piano lid to create dynamic contrasts.

A: And what for? To play Clementi?20)Clementi (1974: 14) was indeed the first composer who considered the ‘greatest effects’ at the keyboard to be ‘of the highest importance’. You know what Mozart said about him, don’t you?

T: I do. It may have had to do with his father’s antipathy towards Italians, and a certain annoyance with Clementi’s undeniable digital talent. For sure that contest at the presence of the Emperor witnessed the greatest creator opposed to the most talented fortepiano tester.21)Piero Rattalino, who describes the fortepiano as a new machine, referred to Mozart as a ‘creatore’, and to Clementi as a ‘collaudatore di una nuova macchina’ (1983: 18). On the other hand, Clementi was very appreciative about Mozart, and said that he never heard anyone play with such taste and grace.

A: Something that he was short of.

T: I don’t know, I regard Clementi as a very interesting composer and I’m not the only one… Beethoven…

A: Beethoven has an antipathy towards long keyboard tutors, and what he sees in Clementi’s piano school is probably the fastest way to teach technique to his students.22)Schindler notes that Beethoven disliked all ‘longer-winded expounding of theory and the even longer-winded practical application [of theory] in the form of etudes, which in the end can do nothing but reduce the pupils to automatons’ (1966: 379-80). Moscheles (1841: 83–84) refers to Beethoven’s appreciation of Clementi as a musician. By the way, Clementi gives some instructions on how to obtain ease and command of the keyboard.23)Clementi (1974: 15) recommended daily practice of scales and exercises.

T: So, you admit that this is something that is now necessary and that Beethoven had realized it!

A: Well…

T: Beethoven constantly adopts Clementi’s new figurations and effects, possesses ‘nearly all of his Sonatas’, and he is also very fond of English pianos (Schindler 1966: 379, in Ringer 1970: 745).24)William S. Newman argued the opposite, namely that Beethoven would not appreciate English instruments and the style they would call for. See his two groundbreaking books: Beethoven on Beethoven and Performance Practices in Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas. More recent research demonstrates that Beethoven was indeed fascinated by the English piano aesthetic, and that, for this reason, he bought an instrument by Erard, ultimately an English piano (see Skowroneck 2002 and 2010). How could a sonata like opus 7 exist without Clementi… or the big F Minor Sonata…25)For further discussion of the influence of the London Pianoforte School on Beethoven, see Ringer 1970. See also Bart van Oort 1993 and 2000. or the ‘drumming’ effect at the beginning of the ‘Waldstein’ Sonata, [Sound Recording] the long pedals in the third movement, and the octave glissando — whose features by the way, are described by Milchmeyer in his tutor well before the composition of the ‘Waldstein’.26)Milchmeyer does not show much appreciation of these kinds of passages, which he calls ‘foolishness’ (1993: 68). Nevertheless, he explains in great detail their execution, which is a sign that they were already in fashion before Beethoven’s authoritative use. Is all this deplorable?

A: I see your point but I don’t necessarily agree. New doesn’t mean good and it doesn’t mean bad. As I look into the new streams of composition, very few people impress me in the matter of true art and sophisticated communication. One of these is of course Beethoven and I see how he is influenced by Clementi and the ‘new’ English school, but don’t forget that he is very much a product of Emanuel Bach’s subtle art of rhetoric and style. Whatever effect Beethoven exploits, it is always part of the structure and becomes a fundamental trait of the general syntax. I can follow Beethoven’s musical ideas, but I’m not sure I can understand Daniel Steibelt’s compositions or a piece like Clementi’s Toccata [Video Recording], which sounds to my ear like mere show-off music. Beethoven’s music is always logical.27)Daniel Steibelt (1765–1823), who, by the way, competed in a contest with Beethoven in Vienna, was considered by Milchmeyer to be one of the most talented ‘pianists’, a creator of and a true expert in piano effects. He himself wrote a piano method, Méthode pour le Piano-forte (1805), but was much opposed by Milchmeyer method’s reviewer, identified as Mr. Knecht (see Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung 1.8 (Nov. 21, 1798), pp. 117-22 and 1.9 (Nov. 28, 1798), pp. 135–37). Steibelt gained some limited success in his time but was seen as a charlatan in learned circles, in the context of a continuing querelle between true artists and Philistines (to anticipate Schumann’s vocabulary).

T: For logical you mean that we can expect what’s going to happen?

A: Not really. Rather, by logical I mean that his music is always related to a logos, a discourse, and thus understandable. When the discourse is weak and effects prevail, we are facing music of poor value.

T: But you admit that effects can be exciting and surprising?

A: Only within a certain frame or structure.

T: Then you might like Domenico Scarlatti’s sonatas!

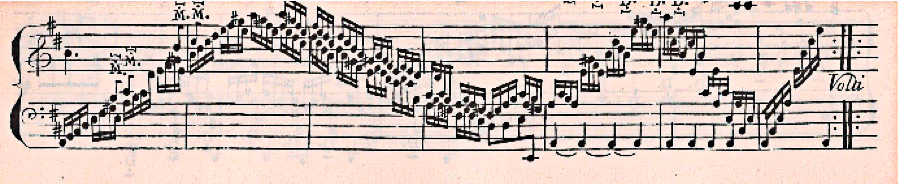

A: Scarlatti always uses a rather simple structure, and plays with it in a very creative way. He is a talented composer, although sometime I don’t understand his almost undoable passages. I’m thinking for instance of the penultimate piece in the collection Essercizi (Figure 1). Why does he write those impossible crossing-hand passages where you could easily play them with a reversed position of the hands?28)For a discussion and history of hand-crossing, see Yearsley 2002. It’s like an ‘obscene surplus of physical energy that seems to refuse all ‘mature’ inhibition’ (Sutcliffe 2003: 285).

T: Those scales in parallel thirds? They are great… they add a risk to the passage. I don’t know whether there’s an artistic reason for doing this but it looks like he deals with the ‘art of technique per se’ something that I would callSpielfreude or Fingermusik (Sutcliffe 2003: 279 (note 6) and 287).29)For a more detailed discussion, see the chapter ‘Una genuina mùsica de tecla’. Yearsley talks about Scarlatti’s technique of hand-crossing as being motivated by a ‘purely arbitrary feat of virtuosity’ rather than dictated by any ‘musical considerations’ (2002: 225). It has to do with ‘materiality’ and asks for a certain ‘physical reaction’ from the listeners (306). I don’t know how many composers use this kind of approach but I think it’s legitimate.

A: I would argue about good taste though.

T: Would you criticize even Frescobaldi when he recommends the player to ‘execute the passage in a resolute way, to show the hand’s dexterity’ (Frescobaldi 1936: III)?

A: Isn’t it show-off time again?

T: I would see it rather as joy of playing, or, in other words, as a joy of being a body while playing!30)In his ‘Note to the reader’, Scarlatti introduces the Essercizi: ‘Do not expect, whether you are an amateur or a professional, to find any profound intention in these compositions, but rather an ingenious jesting with art by means of which you may attain freedom in harpsichord playing’. And goes on: ‘Be more human and less critic; and you will have more fun’. He finishes by saying, ‘Live happy’. Joy and lightness are well expressed in these words, a general wish to be able to combine learning and amusement.

A: Yes, a mindless body.

T: You know what I found? A couple of pages of Mozart’s Fingerübungen. Who knows how many got lost.

A: Are you sure?

T: Of course! KV 626b/48 if you want to check, probably written at the end of 1780.31)There are also two other series of Fingerübungen in the Neue Köchel: Skb 1782a/1: Drei Fingerübungen: Alberti-Bässe und Akkorde mit Fingersatz (18mm); Skb 1782: Zweihändig Tonleiter über zwei Oktaven mit Fingersatz(without bar-lines) to be found in the Neue Mozart Ausgabe (x/30/3). The KV 626b/48 is in NMA ix/27/2 (20); courtesy of Neal Zaslaw, Der neue Köchel, ed. and copyright (2010).

A: Intended for his pupils, for sure!

T: So what? He didn’t think this was a shame, and he added the complete fingering for both hands. Oh, I wish he wrote a Klavierschule, combining grace and power, taste and bravura, singing and brilliant style for he makes such nice use of the fortepiano.

A: I must admit this. He also showed a great appreciation for Andreas Stein’s fortepianos and later, for Anton Walter’s models. Now that we’ve gone into this whole matter, I see that fortepianos lack a tutor for tasteful and skilled playing.32)The birth of the piano was not seen as revolutionary until the very last years of the eighteenth century. Its literature, which is massive and fast in production, has lacked a didactic apparatus for at least the first two decades of use (1780-1800), and even after that, with the foundation of conservatoires and ‘musical mass education’, most methods were shaped as mere containers for sterile finger-exercises. The method that would have represented a complete instruction combining eighteenth-century theory and style with a more modern technique for the piano did not come out until 1828. The voluminous Hummel’s Ausführliche theoretisch-praktische Anweisung zum Piano-Forte-Spielthus summarizes the more prominent aesthetic traits of an entire artistic period, well after its end. Türk still writes with the clavichord in mind, very much following Carl Philip Emanuel Bach’s Essay. He gives only three paragraphs in the Introduction about the right posture at the keyboard and, significantly, places them right before a mechanical discourse about the correct maintenance of the instrument. It’s clear that the other chapters are very much modelled on Bach’s example: some theory rudiments (Chapter I), Fingering (Chapter II), Ornamentation (Chapter III–IV–V), Execution (Chapter VI).

T: What does he say in the chapter on execution then?

A: That chapter is divided conceptually in two: execution and expression. In the latter he deals mostly with the understanding of a piece, again, as a discourse. He keeps comparing music and speech and instructs on rhetoric and declamation. He admits that the ‘highest goal of music’, namely ‘the expression of the prevailing character without which no listener can be moved to any great degree’, can’t be taught because ‘it relies on individual feelings’. According to him, ‘mechanical skill can ultimately be learned by much practice’, and he regards ‘clarity of execution’ and, within this category, ‘mechanical execution itself’, as ‘indispensable’, but he doesn’t give detailed instructions about how to achieve this good ‘pronunciation’ (Türk 1997: 335). All he has to say is:

Mechanical clarity requires that even for the most rapid passage, as well as for essential and extempore ornaments, every tone must be played with its proper intensity, plainly and clearly separated from the others. Those who play with lack of clarity either leave some of the tones out completely (the tones are ‘choked out’ or ‘skipped over’), or at least they are not fully and clearly separated from one another. Similarly, when the keys are struck too hard or too softly, the execution can become unclear. This is also true if the keys are played in a too detached manner, or if the fingers are allowed to remain on the keys too long (324).

T: No clue on how to produce the sound…

A: Exactly. On the other hand he has an extended section of examples in the chapter on fingering. He discusses scales, thirds, sixths, octaves, ninths, and tenths, fast runs, compounded passages with different intervals, chords, alternated and crossing hands, all of these from the point of view of fingering (129—89).

T: I remember that section… I think it is paragraph 72… the one where Türk gives different examples of crossing hands passages without listing one of the most important. He quotes J. S. Bach, W. F. Bach, C. P. E. Bach, Benda, Haydn, Hässler, Kirnberger, and Schulz, but Scarlatti is not mentioned!!!

A: Remember that Germans and Italians are not the best examples of collaboration and mutual respect, and that he may have not known about Scarlatti.

T: This doesn’t seem right. Many German musicians travelled to Italy and made acquaintance with Scarlatti. He was famous as an ‘astounding virtuoso’, whose Fertigkeit at the keyboard was praised by all the people who heard him play.33)The English Thomas Roseingrave and Charles Burney, the German Heinrich Stölzel and Johann Adolph Hasse, not to mention Quantz who heard Scarlatti in 1724, and Händel, who competed with him in 1708 or 1709, encountered the Italian in his home country, and some of them left enthusiastic accounts of his playing. For further discussion, see Yearsley 2002: 231–32. Moreover, Scarlatti wrote probably the most complete and imaginative compendium of keyboard figurations and patterns!!

A: Then you should turn your attention to it, and start examining all his sonatas. He’s actually ‘the first to assert so radically the keyboard’s rights and possibilities of intrinsic material’.

T: But I hope you don’t mean that he’s ‘inventing under the spell of his fertile fingers’… I see it as all the ‘leaps and hand-crossings are undertaken as a demonstration of the keyboard’s musical independence through the medium of technique’!34)This interesting aesthetic nuance and the previous statement are to be found in Sutcliffe 2003: 294.

A: This is very clever, I’ll give you that. But remember, as a good performer you need counterpoint and theory. Don’t forget J. S. Bach and the treatises…

T: I feel prepared for theory and all the requisites you listed at the beginning of our conversation as fundamental for a good keyboardist. But again, I need practical advice on my physical approach.

A: I’m surprised you don’t find the old treatises useful regarding this issue…

T: Whom should I consider?

A: Well, the first tutor of clavichord playing is of course Santa Maria’s Arte de taner fantasia, which was published as early as 1565. And you’ll find some useful remarks about ‘playing with all perfection and artistry’.

According to him, there are eight categories for reaching this purpose:

- To play in accordance with the tactus;

- To maintain a good hand placement;

- To strike keys effectively;

- To play cleanly and distinctly;

- To govern the hands well in running from one part [of the keyboard] to another;

- To play with suitable fingerings;

- To play in good rhythmic style;

- To use effective embellishments.

T: I’m interested in numbers 2, 3, 4 and 5 of this list.

A: Well, his ideal hand placement is shaped like a ‘cat’s paw’.

T: I beg your pardon?

A: Yes, a cat’s paw, where you have a depression before the juncture with the fingers and these are higher than the hand, forming a bow.

T: This is nonsense. The hand will become sore after a while.

A: His reason for this position is that, in this way you’re able to deliver a sharper blow on the keys. It’s like having a bow’s tension followed by a stronger action.

T: But everything is contracted that way…

A: He asks for contraction in the hand. The four fingers should be close together, whilst the thumb should rest at a lower level beneath the palm.

T: ?!

A: Moreover, the little finger has to be contracted more than any of the others to such an extent that it almost reaches the palm.

T: I don’t understand…

A: If the fingers are spread apart from one another, especially the thumb and little [finger], the hands become sluggish, and remain without force or efficacy as if they were bound (Sancta Maria 1991: 92—93). His main concerns are clarity and distinction of execution, and to these aims he designs the whole shape and position of the hand.

T: Do other theorists speak in these terms?

A: Girolamo Diruta in his Dialogo (1969: 4), speaks of ‘seriousness and gracefulness’ in playing the organ.

T: What does this mean?

A: Basically, he asks for a straight position at the keyboard with arms, wrists and hands all lined up.

T: Hands and fingers?

A: Rounded and relaxed hands with curved fingers (4—5).

T: But this is the exact opposite of what Santa Maria says!

A: Well, Diruta writes mostly about organ playing…

T: I find this instruction more applicable to the fortepiano than the previous one!

A: Why?

T: Well, because in the position recommended by Santa Maria, you lose elasticity and consequently speed.

A: It’s actually what Diruta observes.

T: Too bad that he speaks only about organs.

A: He examines plucked instruments as well. And noticing the differences in the production of the sound, he observes that one should compensate for the loss of tone length in the plucked instruments (compared to the organ) with liveliness and hand dexterity (Diruta 1969: 6).

T: Very clever! Now I understand many things. First of all, all those paintings of keyboardists with that impossible arched position of the hands that Santa Maria prescribes… Like Giorgione/Tiziano’s painting entitled Concerto:

A: It’s very difficult to extract rules from paintings, because they are created with other aesthetic concerns than verisimilitude.

T: Yes, but still I think that the rounded position is much more natural and even more beautiful! If you let your arms rest down along your hips, your hands would take that rounded shape naturally. So there must be a real reason to paint that other posture.35) See Brauchli’s articles for further discussion of this topic. The other thing I was thinking of and for which Milchmeyer was sharply criticized by his reviewer, was that he thought that the clavichord was not a good instrument for pupils to be instructed on:

The Piano can be heard with all expression and all possible modifications in the largest halls, and it’s a more secure instrument, in that it does not accustom one to contortions and deformities of the fingers [like the clavichord]. 36)Milchmeyer, p. 9.

Maybe the literature for the clavichord was not so oriented to speed and brilliancy, as was that for the harpsichord for instance!

A: That is for sure, the clavichord was a private instrument and never developed an authoritative voice. However, it does teach many things to pianists, especially regarding touch in the production of the sound and in releasing the keys.

T: Everybody knows that on pianos the sound is produced at the moment the hammer strikes the string, and that it’s meaningless to keep the pressure on a key.

A: Still, everybody knows that the fortepiano’s aesthetic, as with that for the clavichord, has to do not only with dynamics but more especially with notes’ length. How and when you lift a finger from a key can make a whole difference to the affect of a piece!

T: You are right, I had never thought of that…

A: This is what ‘old-style’ treatises actually treat: how to perform within a certain type of aesthetic frame. And if you examine them closer, they will reveal many useful and precious instructions.

T: I will do it then. But we still need to go through the harpsichord tutors. I bet that we will find something interesting, for with the combination of the two manuals, performers probably had to create a good technique for overcoming the heavy resistance of the keyboard!

A: Indeed. There are at least five major treatises for harpsichord and spinet, spanning a little over a century, and among them there is what is considered the first ‘pianoforte tutor’ ante litteram.37)This expression is used by Anna Linde in the preface of the first English Translation of Couperin’s Art of Playing the Harpsichord in 1993 (in Gerig 1979: 14). These are: Jean Denis’Traitè de l’accord de l’Espinette (1650), Michel de Saint Lambert’s Principes du Claveçin (1702), Francois Couperin’s L’art de toucher le Claveçin (1716), J. B. Rameau’s De la Mèchanique des doigts sur le Claveçin (1724), attached to hisPièces de claveçin, and Friedrich Marpurg’s Die Kunst das Klavier zu spielen (1756).

T: Is Couperin’s in a sense the first ‘pianoforte tutor’?

A: Correct. He was very sure of his time’s taste as opposed to the ancient times and gave clear instructions (Couperin 2004: 33).

T: The title of Rameau’s essay has always intrigued me because it mentions ‘mechanics’ with regard to efficiency in playing. If I remember well, his first remark is, ‘perfection in playing the harpsichord consists mainly of a well-directed movement of the fingers’ (Rameau 1724: 135). This implies a rational system in playing. What I don’t understand is why all of the theorists have so much modesty in instructing about mechanical rules, while all the other matters are widely analyzed and taught. This must be because of the old conviction that if one is not naturally gifted, especially as a musician, there is no hope for making a living by this art.

A: Would you argue with that?

T: I know it is true, but there are endless nuances in one person’s talent and what is easier for someone may be less so for another. If you exclude one area of teaching, such as how to optimize your posture at the instrument, you dismiss a potential good musician who may have less facility in execution matters though he might have nice ears and taste.

A: Mmmmhhh… Maybe this whole subject was taught in an oral way…

T: The rationalists believed in the power of education and environment, and wouldn’t neglect any aspect of sciences and arts. That’s why this is so interesting!

A: I have to admit that it is interesting. In leafing through these books, my eyes stop on particular words. Saint Lambert refers to the ‘convenience’ of the player, which he puts before ‘gracefulness’ (1984: 74).38)The word in the original reads ‘commodité’. Marpurg (1974: 71) mentions these two words as well but sees them as bound together in the negative idea that ‘la mauvaise grace accompagne pour l’ordinaire une position incommode’. Couperin says that ‘proficiency in execution is what is expected today’, and pushes towards more professional performances (2004: 13). At the same time he speaks of liaison, a perfect slur with which one should play, and his way of fingering for the first time makes a step towards a legato style as we think of it now (33).

T: Is that why his manual is considered to be the first ‘piano method’?

A: This is only part of the reason. In fact, he is the first theorist to offer a systematic, step-by-step instruction in how to develop a good technique and improve memory (12).

T: He’s probably the first one to treat this latter subject.

A: Besides, I’ve just realized he talks about tone production! He writes:

A delicate touch depends also on holding the fingers as close to the keys as possible. Experience aside, it is reasonable to assume that a hand which attacks the keys from a height is going to produce a sharper tone than one which approaches them from a point closer to the keyboard (in Letnanova 1991: 12).

T: Here we are!

A: There’s more. He talks about a good posture at the keyboard, and is not the first to do so. Before him, Jean Denis, who wrote the first French treatise devoted exclusively to keyboard performance practice, approached the issue of good posture while playing:

There are some masters who have their pupils place their hands in such a way that the wrist is lower than the hand, which is very bad, and properly speaking, a vice, because the hand no longer possesses strength. Others make one hold the wrist higher than the hand, which is a fault because the fingers then resemble sticks, straight and stiff. For the proper position of the hand, the wrist and the hand must be at the same height; in other words, the wrist must be at the same height as the large knuckle of the fingers… It is wonderful to behold a person who plays well and gracefully, and whose hand is correctly positioned. But one must be very careful not to play with either force or tension, for he who is tense or strained in his hands or in his body will never play well (Denis 1987: 3).

And here comes something that you are concerned with, namely flexibility in teaching every aspect of music, and trying to apply it to one’s own capabilities:

Masters who teach should carefully consider the ability of the person who is being taught: whether he is capable of playing according to the rules, and whether his fingers can do so. For if it is wished that a person play the cadential trill with the last two fingers and these fingers cannot do so without strain, he should be allowed to play this trill with the first two fingers and cut it off subtly with the second finger, as I do. If I had sought to compel myself to do it as it is supposed to be done, I would never have played the harpsichord or the organ as well (97 and 100).

T: A nice example of wisdom and common sense… although there are always objective rules for better playing.

A: Marpurg claims that ‘there is nothing as arbitrary as the position of the fingers for harpsichordists’.

T: But he also says that ‘there is always one which is more convenient for ease’ (Marpurg 1974: 71). If everything was entirely subjective, humanity wouldn’t progress as it does… even taste obeys general rules.

A: But it varies from place to place and from time to time. Nevertheless yours is a good argument worthy of an Enlightenment artist.

T: I’m only an Executor…

A: Aristotle, the founder of the scientific method, went on from observation and experiments to the understanding of immutable natural laws. This is a typical strategy for acquiring knowledge.

T: I’m happy that you think this way. Rameau was another who argued in that sense. He observed how the natural position of the hand is the rounded one, and described how our body works on a keyboard:

The movement of the fingers derives, so to speak, from the joint to which the hand is attached, and never elsewhere; the one of the hand derives from the joint of the wrist, and the one of the arm, supposing that it were necessary, derives from the joint of the elbow. The greater movement ought not to take place except when the lesser will not be enough: and similarly, when a finger is able to reach a key without moving the hand, but only by stretching or opening [the fingers], one should take care not to lavish the movement beyond necessity (1724: 135—36).

He noticed how each finger should be independent from the others and should play only with its own action, and that the most important qualities in good execution are lightness and liveliness (légereté et vitesse), both of which are acquired through evenness (égalité):

Lightness and liveliness are to be acquired only through evenness of movement … One should try to acquire the necessary movement with the fingers, and to give to each of them its individual movement, before putting their force … to the test. Never burden the touch of your fingers by the effort of the hand; on the contrary, let your hand be shaped so that, when lifting your fingers, it renders their touch more light; this is matter of great consequence (135—36).

A: Does he mention how to achieve this independence with the fingers?

T: Yes he does. He found that the technique of lifting one finger and contemporaneously pressing a key with another is effective’ (135—36).

A: You talked about dissociation. Is this what you meant?

T: I don’t know. Rameau is really clever in explaining everything. He is the first who affirms clearly that the wrist should always be relaxed, but according to my own experience, this method of finger articulation works only partially on a fortepiano.

A: Why?

T: In this way, the hands get tired after scales and fast passages, and if you need to play alternating double notes like thirds, your fingers get stuck.

A: What would you propose then?

T: Work on the dissociation of the tendons, meaning that you train all your fingers to do the same thing at the same moment, the exact opposite of what Rameau prescribes.

A: I’m confused now.

T: Well, dissociation between flexors and extensors means that when one finger is pressing a key — the consequence of a flexor tendon action — the others should be with it.

A: Pressing keys?

T: No, just not using the extensors. Before playing the next note, all the other fingers raise with the one that is going to play and fall down with it. But it is very complicated to put in words.

A: Maybe that’s why nobody did.

T: Or rather, nobody did it because they were satisfied with their technical needs.

A: The harpsichord technique sounds very sophisticated, and it is probably where all the keyboard theorists of the second half of the eighteenth century took their knowledge from. Rounded hands, no effort, lightness…

T: It is clear that common sense and some scientific observation push towards ‘economy’ in playing. If I remember well, all the harpsichord treatises suggest the employment of only necessary movements.39)Saint Lambert says that ‘the basic principle of fingering is to choose fingers that make the hand move the least’ (1984: 74 n. 8), and so does Marpurg (1974: 72). See also the first of the two long quotations from Rameau in this text.

A: Indeed. And so did Emanuel Bach and Türk.

T: But I feel that the new instrument, the fortepiano, needs its own rules, which nobody has taken the trouble to write down.

A: Maybe nobody observed them appropriately. Also, theorists of the second half of the eighteenth century were much more interested in abstract forms of knowledge, summarizing rules of procedure, and attempting to define a common ground for taste which, during the time between Emanuel Bach and Türk, had already changed considerably.

T: Milchmeyer made some observations…

A: It is hard to trust one like him. I see his cleverness at inventing and experimenting but he lacks basic knowledge of taste and musical tradition. Somebody showed me recently two new manuals, both published in London. One is Jan Ladislav Dussek’s Instructions on the Art of Playing the Piano-Forte or Harpsichord, published in 1796, one year before Milchmeyer’s own book, the other one is Clementi’s Introduction to the Art of Playing on the Piano Forte, published in 1801…

T: Clementi wrote a piano method!!!

A: Yes… I already mentioned it at the beginning of our exchange… Maybe you weren’t listening…

T: How come that I didn’t know about it?

A: You were too busy with your own observations and experiments at the keyboard. But now, go and look at them. Although they rely much on the harpsichord tutors regarding technique, they may be of interest for your purposes.

T: I will never thank you enough for this enlightening conversation.

A: You’re very welcome. I enjoyed finding out about your thoughts on technique as an artistic matter.

Footnotes

References

| ↑1 | The dedicatees of the two tutors appear to be quite different. Türk addresses his work to ‘students, teachers, scholars who can give to music matters further reflection on different topics’ (Türk 1997: 2); Milchmeyer writes for ‘amateurs and beginners of pianoforte playing’ (1993: 3). Regarding the evolution of the categories of Dilettanten and amateurs, it should be said that, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and as long as the consumption of music was associated with the nobility or with the dawn of the bourgeoisie, the terms did not indicate level of skill or knowledge in music but the fact that it did not represent a profession. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Not only keyboard methods followed this model. The violin tutor, Elementi teorico-pratici di musica, by Francesco Galeazzi, for instance, stresses the importance of theory first, followed by practice (1791: 52). |

| ↑3 | Since Plato, dialogues have been the favourite formats for delivering knowledge in a creative way. Through the dialogue between two or more contrasting personae, a higher synthesis is usually reached. During the Renaissance and after, scientists and theorists in general used the ‘dialogue’ to organize serious treatises and essays in a lighter and more agreeable way (Galileo was one of them as was Diruta in Il Transilvano). I recommend the charming multiple-voice dialogue by Elizabeth Le Guin, ‘A Visit to the Salon de Parnasse’ in Haydn and the Performance of Rhetoric (Beghin/Goldberg, eds). Although the idea of my dialogue came before reading Le Guin, I consider her essay a brilliant confirmation of my purpose. |

| ↑4 | In his Essay, Carl Philip Emanuel Bach warned against mere virtuosi who were capable of only playing the correct notes: ‘They overwhelm our hearing without satisfying it, and stun the mind without moving it’ (see § 1 in Chapter III ‘On Performance’). On the other hand, the word ‘virtuoso’ had a positive definition in earlier times. See, for instance, Adriano Banchieri’s caste division of musicians and organists into Vittoriosi; angels, saints and the celestial court, Virtuosi; religious and lay people who play in churches in God’s praise, and Vitiosi; ambitious and seditious musicians who play for mundane praises and interests) (1609: 64). At the time of its appearance, virtuosodefined somebody who had exceptional talent in intellectual, artistic, scientific or ethical subjects. In the Italian environment, the term had a strong relation with music, composers and performers. At the beginning of the eighteenth century in Germany, a virtuoso was a musician who possessed exceptional theoretical knowledge, and who applied it to composition or practical matters. Since about 1740, the term evolved to mean ‘concertists’, which was probably the first time that the term took on both positive and negative significance, this latter having to do with showing technical abilities for the sake of exhibition and self-affirmation. For a comprehensive history of the term virtuoso, see the entry in Eggebrecht, vol. 6. |

| ↑5 | Gravecembalo col piano e col forte was the first name for an instrument that presented all the basic characteristics of a fortepiano: hammer-struck strings, an action with the so-called ‘escapement’ of the hammers, and more generally the possibility of modulating dynamics. The credited inventor of the first fortepiano was Bartolomeo Cristofori from Padua, later an employer at the Medici court in Florence. A catalogue entry lists one of these instruments that was built in 1700. |

| ↑6 | Couperin discusses two techniques to modify the effect of the tone by either shortening or delaying it. According to him, these techniques give the illusion of dynamic changes on the harpsichord (Couperin, in Letnanova 1991: 24). |

| ↑7 | Milchmeyer, who wrote the first German piano method expressly meant for the pianoforte, was the first theorist to remark on the fact that, because the clavichord was almost impossible to hear, nobody would have picked it as an instrument for a concert (Milchmeyer 1993: XII). |

| ↑8 | Milchmeyer was at service at court in Mainz as an inventor (acc. to Gerber; in Milchmeyer 1993: XIII). Every court had a Hofmechanicus, who could also be a musician, on their staff. Rhein points out (ibid. IX–X) that Milchmeyer was a minor figure on the music scene: ‘his compositions are negligible, his teaching produced no notable performers, and he appears not to have been personally acquainted with any of the major musical figures of his time’. Moreover, he did not have the same literary talent as Quantz or Emanuel Bach. It is clear therefore how far removed he was from the mainstream music scene. I am most grateful to my colleague Christina Kobb for having pointed out an article by Michael Latcham of 2002 (‘Swirling from one level of the affects to another: the expressive Clavier in Mozart’s time’ in Early Music, XXX/4), where he quotes Milchmeyer’s own description in an 1783 advertisement about a ‘mechanical Flügel which can change more than 250 times by mixing the stops’. (The advertisement is found in Cramer: Magazin der Musik für das Jahr 1783, p. 1027; its reference in Latcham, p. 505). This notice contradicts what was previously believed about Milchmeyer’s invention, namely the fact that his three manual harpsichord had 250 stops. Latcham remarks that ‘250 combinations need at least eight stops’ (footnote 18, p. 516). |

| ↑9 | Emanuel Bach writes that the art of ornaments ‘requires a freedom of performance that rules out everything slavish and mechanical’. He suggests that one should ‘play from the soul, not like a trained bird’ (Bach 1949: 150). |

| ↑10 | In his treatise on the harpsichord, Couperin dealt with the importance of not forcing a child to play a multiple-manual instrument, which, he wrote, ‘will unavoidably strain his small hands to produce sound from the strings; this will result in a bad hand position and harshness in execution’ (in Letnanova 1991: 12). |

| ↑11 | Despite Forkel’s forthright view of the subject, it is not clear whether J. S. Bach was so fond of the clavichord. There is no evidence regarding the instruments that he possessed or the pieces that he may have written especially for the clavichord. See Schweitzer, pp. 200ff. Letnanova (93) reports Forkel’s argument about the clavichord without questioning it. During Bach’s time, ‘Clavier’ or ‘Klavier’ referred to a general category of ‘keyboard instruments’ (Forkel still adopts it with this meaning), while in the second half of the eighteenth century it came to define the clavichord, at least in the Germanic states. For more details, see the Introduction to Türk’s Klavierschule, § I, wherein he lists ‘organ, harpsichord, and the pianoforte’ beside the ‘true Klavier’, or clavichord. |

| ↑12 | Not so much attention was paid to physical matters when playing an instrument at this time. J. S. Bach and Couperin were revolutionary pedagogues but generally music teaching involved more theoretical subjects. Eventually, during the course of the nineteenth century the distinction between correct and beautiful performance encouraged teaching to focus on expression and taste, both related to ‘beautiful performance’. Of course, what can be taught and what cannot is still debated in pedagogic circles. |

| ↑13 | ‘I have often wondered why C. P. E. Bach’s Essay on the Right Manner of playing the Clavier does not elucidate the qualities that constitute a good touch. For, he possessed in high degree the technique that made his father pre-eminent as a player. True, in his chapter on ‘Style in Performance’, he writes, “some persons play as if their fingers were glued together; their touch is so deliberate, and they keep the keys down too long; while others, attempting to avoid this defect, play too crisply, as if the keys burnt their fingers. The right method lies in between the two extremes”. But it would have been more useful had he told us how to reach this middle path’ (Forkel 1920: 50). |

| ↑14 | That is, § 4 ‘On Fingering’: ‘Correct employment of the fingers is inseparably related to the whole art of performance. More is lost through poor fingering than can be replaced by all conceivable artistry and good taste. Facility itself hinges on it, for experience will prove that an average performer with well-trained fingers will best [sic] the greatest musician who because of poor fingering is forced to play, against his better judgment’. |

| ↑15 | The keywords in the treatises from this time are Geschmack (taste) and Art. In the introduction to his book, Quantz lists these qualities as the ones that every musician should have (1966: 11); and in the chapter on ‘Good Performance’, Emanuel Bach admits the importance of equally developing the capabilities of both hands and that ‘good taste should be cultivated in the student right from the very beginning’ (in Letnanova 1991: 40). |

| ↑16 | According to Ratner (1980: 422), these are new trends in music after 1800. |

| ↑17 | It was commonly thought that a musician was an orator, ‘who with sonorous and gentle voice delights and moves’ (Banchieri 1975: 58). Emanuel Bach wrote that ‘the keyboardist more than any other executant can practice the declamatory style, and move audaciously from one affect to another’ (1949: 153). For an extended discussion of the declamatory style and music in the eighteenth century, see Barth, 1992. |

| ↑18 | ‘On the whole, the English public, anticipating its Continental counterparts by more than a generation, favored a domesticated type of musical art catering to short-range emotional effects, often at the expense of structural solidity and logic’. Ringer (1970: 744) calls this an ‘escapist mentality’. |

| ↑19 | Bach, Autobiography quoted in the Introduction to his Essay (1949: 16). Bach associated the style of Brechen or Arpeggiare — namely playing a chord by separating it into the individual notes, one after the other — with Italy. From harp playing, this style invaded keyboard practices and in particular harpsichord-playing. Bach blamed Italians for their tendency to roll chords, evidently a negative trait for him as ‘mere’ effect. He writes: ‘They can scarcely play a chord without breaking it’ (316, see also Burdette 1989: 4–6). These broken chords were common also in France. Couperin gives many examples of what he calls ‘batteries’ (Letnanova 1991: 15). |

| ↑20 | Clementi (1974: 14) was indeed the first composer who considered the ‘greatest effects’ at the keyboard to be ‘of the highest importance’. |

| ↑21 | Piero Rattalino, who describes the fortepiano as a new machine, referred to Mozart as a ‘creatore’, and to Clementi as a ‘collaudatore di una nuova macchina’ (1983: 18). |

| ↑22 | Schindler notes that Beethoven disliked all ‘longer-winded expounding of theory and the even longer-winded practical application [of theory] in the form of etudes, which in the end can do nothing but reduce the pupils to automatons’ (1966: 379-80). Moscheles (1841: 83–84) refers to Beethoven’s appreciation of Clementi as a musician. |

| ↑23 | Clementi (1974: 15) recommended daily practice of scales and exercises. |

| ↑24 | William S. Newman argued the opposite, namely that Beethoven would not appreciate English instruments and the style they would call for. See his two groundbreaking books: Beethoven on Beethoven and Performance Practices in Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas. More recent research demonstrates that Beethoven was indeed fascinated by the English piano aesthetic, and that, for this reason, he bought an instrument by Erard, ultimately an English piano (see Skowroneck 2002 and 2010). |

| ↑25 | For further discussion of the influence of the London Pianoforte School on Beethoven, see Ringer 1970. See also Bart van Oort 1993 and 2000. |

| ↑26 | Milchmeyer does not show much appreciation of these kinds of passages, which he calls ‘foolishness’ (1993: 68). Nevertheless, he explains in great detail their execution, which is a sign that they were already in fashion before Beethoven’s authoritative use. |

| ↑27 | Daniel Steibelt (1765–1823), who, by the way, competed in a contest with Beethoven in Vienna, was considered by Milchmeyer to be one of the most talented ‘pianists’, a creator of and a true expert in piano effects. He himself wrote a piano method, Méthode pour le Piano-forte (1805), but was much opposed by Milchmeyer method’s reviewer, identified as Mr. Knecht (see Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung 1.8 (Nov. 21, 1798), pp. 117-22 and 1.9 (Nov. 28, 1798), pp. 135–37). Steibelt gained some limited success in his time but was seen as a charlatan in learned circles, in the context of a continuing querelle between true artists and Philistines (to anticipate Schumann’s vocabulary). |

| ↑28 | For a discussion and history of hand-crossing, see Yearsley 2002. |

| ↑29 | For a more detailed discussion, see the chapter ‘Una genuina mùsica de tecla’. Yearsley talks about Scarlatti’s technique of hand-crossing as being motivated by a ‘purely arbitrary feat of virtuosity’ rather than dictated by any ‘musical considerations’ (2002: 225). |

| ↑30 | In his ‘Note to the reader’, Scarlatti introduces the Essercizi: ‘Do not expect, whether you are an amateur or a professional, to find any profound intention in these compositions, but rather an ingenious jesting with art by means of which you may attain freedom in harpsichord playing’. And goes on: ‘Be more human and less critic; and you will have more fun’. He finishes by saying, ‘Live happy’. Joy and lightness are well expressed in these words, a general wish to be able to combine learning and amusement. |

| ↑31 | There are also two other series of Fingerübungen in the Neue Köchel: Skb 1782a/1: Drei Fingerübungen: Alberti-Bässe und Akkorde mit Fingersatz (18mm); Skb 1782: Zweihändig Tonleiter über zwei Oktaven mit Fingersatz(without bar-lines) to be found in the Neue Mozart Ausgabe (x/30/3). The KV 626b/48 is in NMA ix/27/2 (20); courtesy of Neal Zaslaw, Der neue Köchel, ed. and copyright (2010). |

| ↑32 | The birth of the piano was not seen as revolutionary until the very last years of the eighteenth century. Its literature, which is massive and fast in production, has lacked a didactic apparatus for at least the first two decades of use (1780-1800), and even after that, with the foundation of conservatoires and ‘musical mass education’, most methods were shaped as mere containers for sterile finger-exercises. The method that would have represented a complete instruction combining eighteenth-century theory and style with a more modern technique for the piano did not come out until 1828. The voluminous Hummel’s Ausführliche theoretisch-praktische Anweisung zum Piano-Forte-Spielthus summarizes the more prominent aesthetic traits of an entire artistic period, well after its end. |

| ↑33 | The English Thomas Roseingrave and Charles Burney, the German Heinrich Stölzel and Johann Adolph Hasse, not to mention Quantz who heard Scarlatti in 1724, and Händel, who competed with him in 1708 or 1709, encountered the Italian in his home country, and some of them left enthusiastic accounts of his playing. For further discussion, see Yearsley 2002: 231–32. |

| ↑34 | This interesting aesthetic nuance and the previous statement are to be found in Sutcliffe 2003: 294. |

| ↑35 | See Brauchli’s articles for further discussion of this topic. |

| ↑36 | Milchmeyer, p. 9. |

| ↑37 | This expression is used by Anna Linde in the preface of the first English Translation of Couperin’s Art of Playing the Harpsichord in 1993 (in Gerig 1979: 14). |

| ↑38 | The word in the original reads ‘commodité’. Marpurg (1974: 71) mentions these two words as well but sees them as bound together in the negative idea that ‘la mauvaise grace accompagne pour l’ordinaire une position incommode’. |

| ↑39 | Saint Lambert says that ‘the basic principle of fingering is to choose fingers that make the hand move the least’ (1984: 74 n. 8), and so does Marpurg (1974: 72). See also the first of the two long quotations from Rameau in this text. |